Jim Gerhart, March 2020

Movies, or moving pictures as they were first known, were invented in the 1890s. Within ten years, theaters devoted to showing movies began to proliferate. The first four large movie theaters in Lancaster were built between 1911 and 1914. They were the Colonial, Hippodrome, and Grand on North Queen Street, and the Kuhn on Manor Street. The three downtown theaters were more opulent and charged higher prices than the Kuhn, which was established to serve the working-class southwest Lancaster neighborhood.

The Kuhn Theatre, also sometimes known as Kuhn’s Theatre, opened in March 1911. Adam Kuhn was a German immigrant who attended St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, and who for many years, ran a successful bakery on East Chestnut Street. After much of his bakery was destroyed in a fire, he decided to retire from the baking business and venture into the new movie-theater business. He sold the damaged bakery in September 1910 and a month later he used the proceeds to buy a large lot in the 600 block of Manor Street for $1,950 (the lot was actually purchased in the name of Mary, his wife). On that lot, Kuhn built the Kuhn Theatre, which would eventually become the Strand Theatre and continue showing movies until 1962.

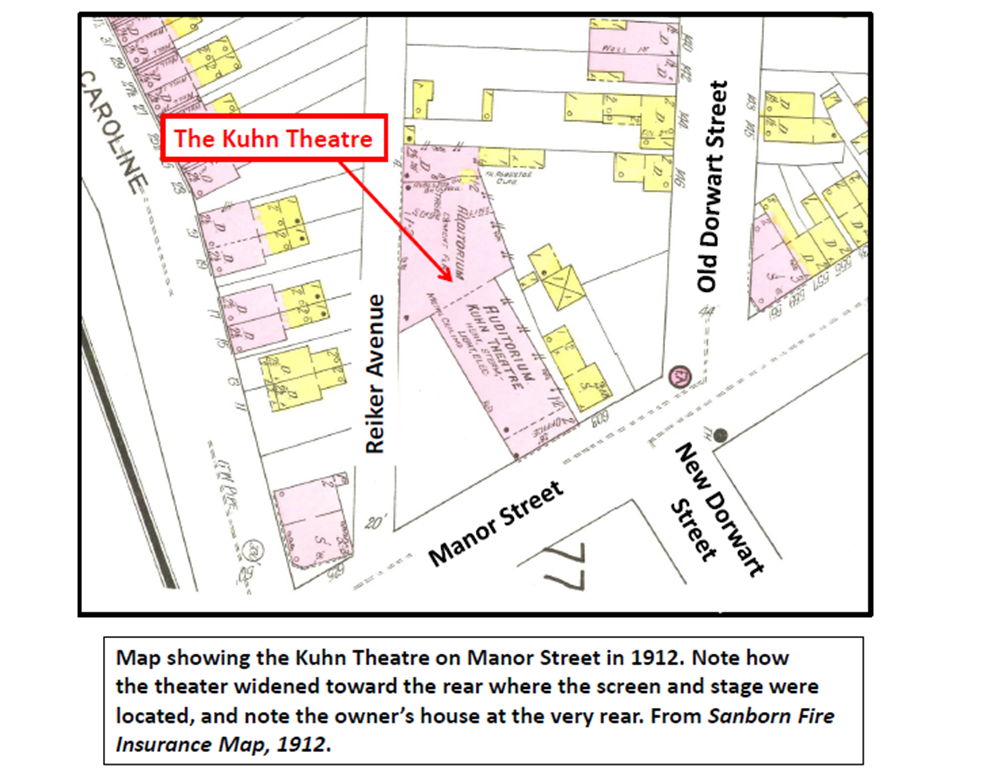

The Kuhn was located at 605-609 Manor on a large lot that extended to Reiker Avenue, and it stood nearly alone on that part of the block when it was first built. The brick theater had 40 feet of frontage on Manor, widening to 70 feet where the screen and stage were at the rear of the building. The building was 205 feet long, with a two-and-a-half-story brick house attached to the rear of the theater, in which the Kuhn family lived. The original theater, which could seat 400 people, was heated by steam and had both gas and electric lights. (The former site of the now demolished theater is a parking lot next to B&M Sunshine Laundry.)

Adam Kuhn’s new career in the movie-theater business did not last very long. He died in the fall of 1912. Edward J. Kuhn, Adam’s son, took over ownership of the theater. Like most movie theaters in the early days, it not only offered movies, but also offered other types of entertainment such as vaudeville acts and band music. Kuhn also rented out the theater for use by others; one example was the Salvation Army for evangelistic services in 1914.

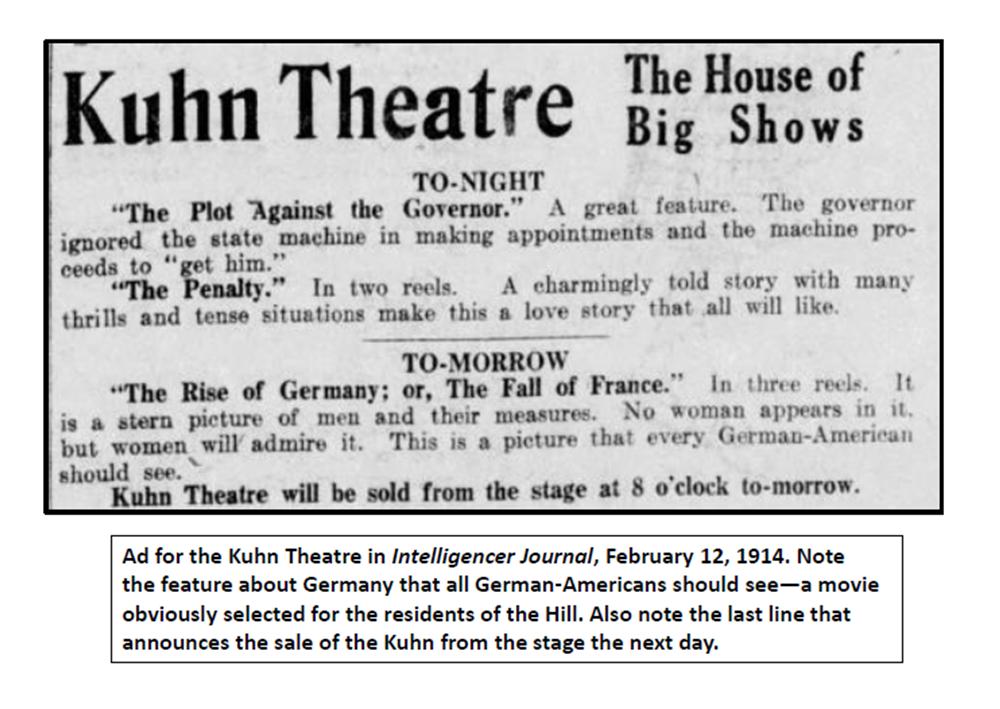

The movies shown at the Kuhn were quite primitive, black-and-white, silent movies that featured exaggerated acting and were usually about 15-45 minutes long. Each movie consisted of one to three reels of film; if there was more than one reel, the projectionist had to rewind and change the reels while the audience waited. The movies were accompanied by live piano music. Kuhn charged a nickel for most movies, and a dime for special events.

Edward Kuhn operated the theater through 1913, but in early 1914, he put the theater up for sale at auction. The advertisement for the public sale, held in the theater in February 1914, noted that the theater had been “a good money maker”. The highest bid was $15,000, but that was less than Kuhn thought it was worth, so the theater was withdrawn from sale. Kuhn tried again two weeks later, but again the theater was withdrawn from sale. Six months later, in August 1914, the theater was seized and sold to cover Kuhn’s debts. The Northern Trust Company bought the theater for $7,300. A couple months later, in October 1914, the Northern Trust Company sold it to two theater operators from Philadelphia for $8,300.

The two new owners, Peter Oletzky and Michael Lessy, changed the name of the theater to the Lancaster Theatre, and continued to offer movies and other forms of entertainment while remodeling the theater and increasing the seating capacity to about 900. By January 1916, a new theater manager had been brought on from Philadelphia. While movies were still the theater’s mainstay, other large events were held to augment the theater’s income. One such event was an April 1916 show put on by the Eighth Ward Minstrels accompanied by the St. Joseph’s Church orchestra and choir that attracted more than 1,000 people.

A big change in the program of the Lancaster Theatre was the addition of boxing matches. A boxing ring was set up on the stage for these events, and well-known local and regional boxers would stage matches that attracted packed houses. One example was a bout between Cabbage Hill’s own Leo Houck and Dummy Ketchell of Baltimore.

The Lancaster Theatre got another new manager in October 1916, and he announced a new policy of “musical comedy playlets of the higher class and unexcelled photoplays”. The opening act under this new policy was Rowe and Kusel’s Big Girlie Musical Review, an act that may have indeed been a change for the family-oriented audiences of the Hill. Prices were 5, 10, or 15 cents, depending on the seats. On the downside, because of competition from other attractions in the summer months, the Lancaster Theatre closed down for the entire summer in 1917.

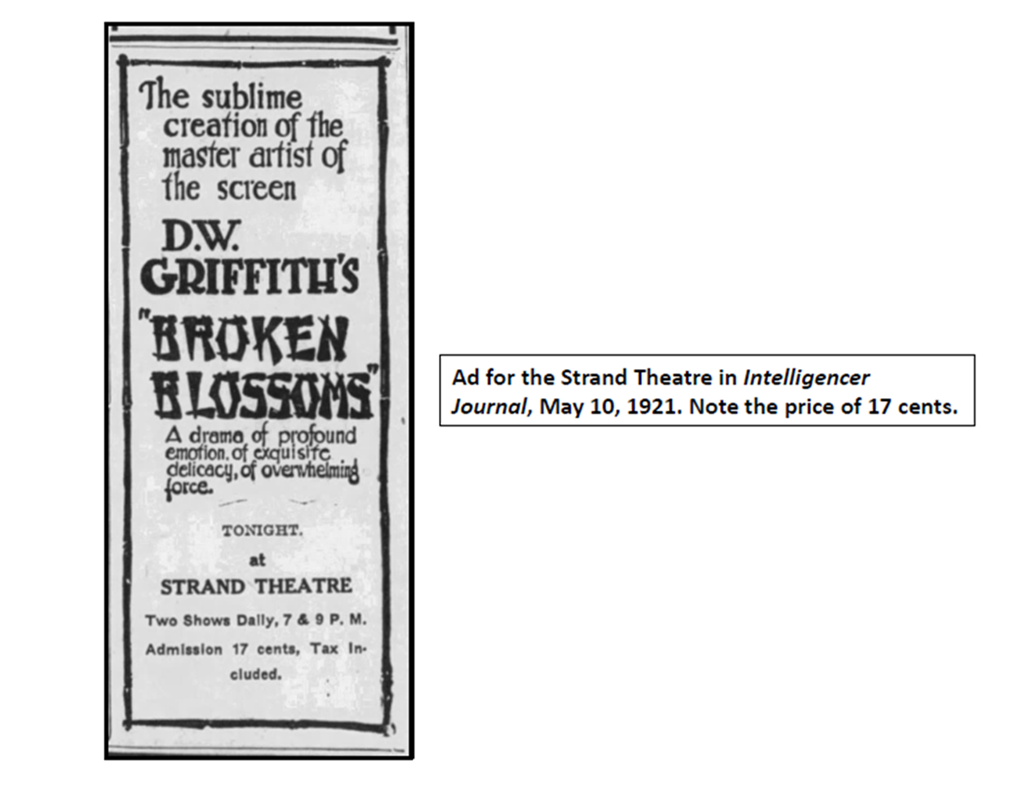

By the spring of 1919, the theater had changed hands again, and was doing business under the name of the Manor Theatre. Movies and boxing matches continued to be the two main draws. Movies had become much more sophisticated in the eight years since the theater had opened. They were still silent, but they had become longer, with more natural performances, and instead of anonymous actors, they now had recognizable stars who drew people to their movies. They also were now being made in Hollywood, California, instead of New York and New Jersey.

Other attractions drew crowds as well, such as a 7-foot eel caught by George Schaller, a neighborhood cigarmaker, in January 1920. Schaller put the eel in his backyard to freeze it solid, and then put it on display in the Manor Theatre. However, a monster eel was apparently not enough to meet the Manor’s profit expectations, and the theater was sold again in the spring of 1920, this time to George Bennethum of Philadelphia for $15,000. He remodeled the theater, updated its projection equipment, and changed the name of the theater to the Strand, a name it would keep until it closed 40 years later. Movies were still the staple, but boxing and other events also were staged. For instance, in the winter of 1921-22, the Duquesne Boxing Club leased the theater for its winter season of matches.

In 1928, the Strand Theatre was sold to Harry Chertkoff, a Latvian immigrant who would own it until he died in 1960. Chertkoff went on to own numerous other theaters in Lancaster County, including the King Theater and the Sky-Vue and Comet drive-ins. His first infrastructure improvement at the Strand was to outfit it for sound to accommodate the industry’s switch to movies with soundtracks. Chertkoff also made major renovations to the Strand in 1933 with the addition of improved acoustics and speakers, and again in 1939 with air conditioning and new seats. He also continued the practice of keeping prices as low as possible. In 1948, when Lancaster City instituted a 10% amusement tax, Chertkoff upped his prices to a still modest 37 cents for adults and 15 cents for children.

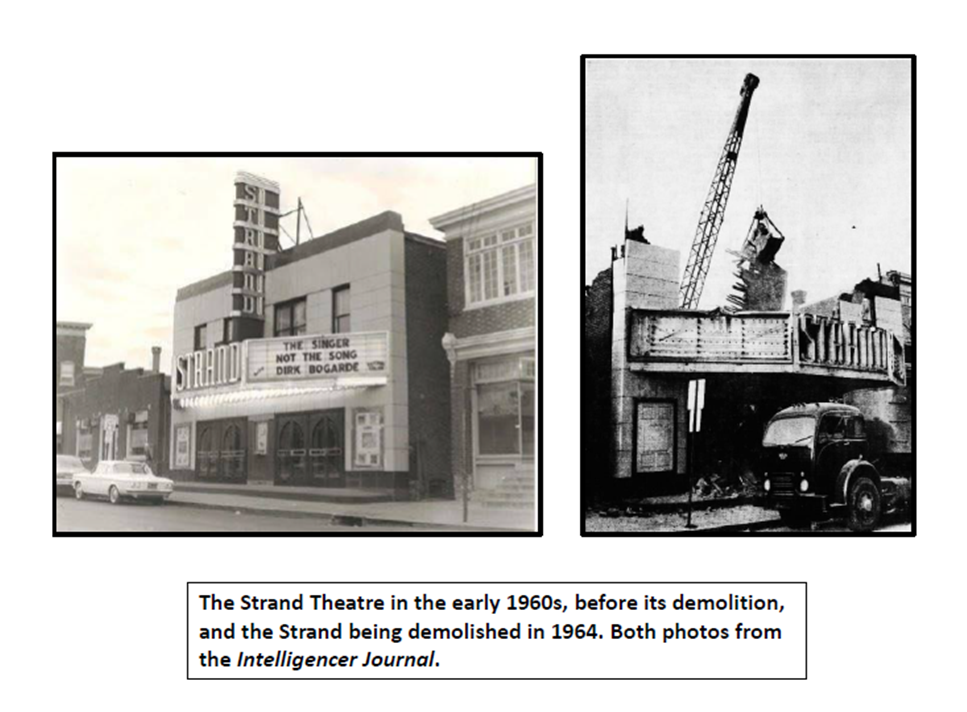

After Chertkoff’s death in 1960, his son-in-law Morton Brodsky took over his business interests. The Strand had been losing money for several years, probably related at least partly to the rising popularity of television. In 1962, the theater stopped showing movies, and Brodsky decided to sell the property. While searching for someone to buy the lot and building, Brodsky proceeded to sell the seats, projection equipment, and screen. When the theater building didn’t sell, he decided to just tear it down, and in November 1964, the Strand was demolished. Brodsky stated that he was exploring several options for the site, but in the short term it would be graded and used for parking, which turned out to be the long-term plan as well, as the site is still a parking lot today.

The Kuhn/Lancaster/Manor/Strand Theatre was Lancaster’s only neighborhood theater; all the others were downtown. It was the entertainment center of the Hill, providing movies and other amusements at reasonable prices to Hill residents for more than 50 years. Many a child had his or her early movie experience in the theater, including yours truly in the early 1960s. The 1964 demolition of the last incarnation of the theater, the Strand, not only left a physical gap in the 600 block of Manor, but also a gap in the social and cultural environment on the Hill.