Jim Gerhart, May 2020

What do an extension table, a dumping coal wagon, a hospital bed, a meat slicer, a reclining chair, a burglar alarm, and a fire ladder have in common? They were all patented right here in Lancaster, on Cabbage Hill!

Their inventor was Anthony Iske, who is said to have held some 200 patents for a wide variety of devices from about 1860 to 1910. Iske, who was known as the Edison of Lancaster, was a skilled and industrious immigrant who led a remarkable life, greatly contributing to the vitality and culture of the Hill and the rest of Lancaster.

Antoine (Anthony) Iske was born in Alsace, France, in April of 1831. When he turned 14, he became an apprentice in his grandfather’s cabinetmaking business. He quickly learned the trade, and by the time he was 18, he was in charge of his grandfather’s shop, which had an excellent reputation for fine furniture, with a specialty in church altars.

In the spring of 1853, Anthony received an invitation to cross the Atlantic to build an altar for a new church in Lancaster, New York. Upon his arrival in New York City, he was directed to the wrong train and arrived here in our Lancaster instead. Luckily, our Lancaster also had a new church that needed an altar, and Iske was hired to build the high altar, two side altars, and a pulpit for the new St. Joseph Catholic Church, a task he completed in 1854 at the age of 23.

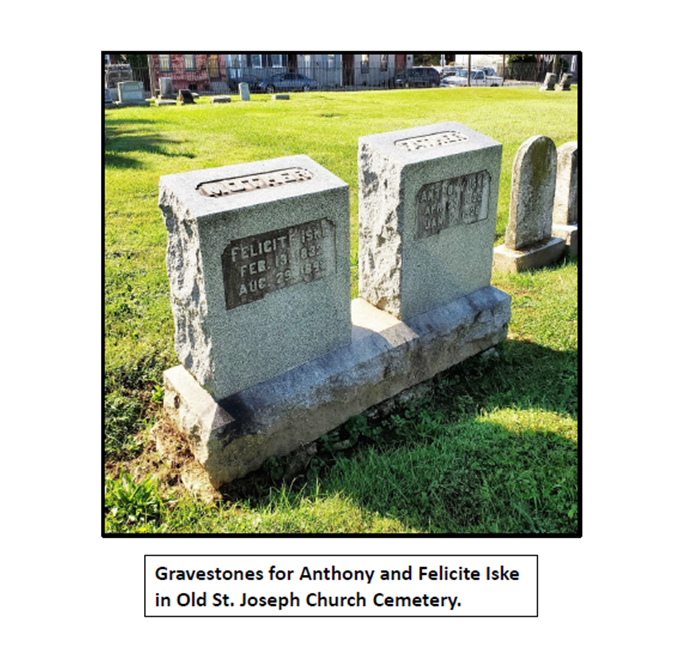

Less than a month after arriving in Lancaster in 1853, Anthony married Felicite Ruhlman, another immigrant from Alsace who had traveled on the same ship. Soon, Felicite gave birth to a daughter who unfortunately died four days later. Over the next ten years, they would have five more children, three of whom—Albert, Emma, and Laura—would survive to adulthood.

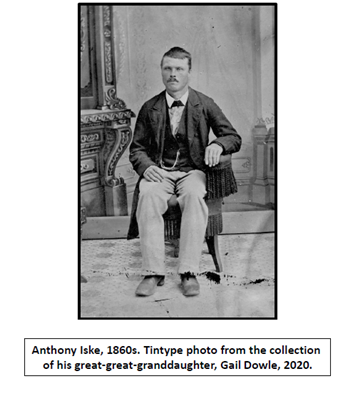

By 1858, the Iskes were tenants in a house in the middle of the 400 block of High Street, and Anthony had set up his furniture business there. He not only made furniture of all types, but by the beginning of the Civil War he also made coffins and ran an undertaking business in his workshop on High (see 1864 ad). In addition, he continued to be sought after for church furnishings. One example was a 25-foot-tall pulpit he built in 1864 for St. Augustine Catholic Church in Pittsburgh.

He also began to invent, and seek patents for, a wide variety of wood and metal devices, some of which were the first of their kind and others that were improved versions of existing devices. Some of his inventions from these early years included an extension table, a dumping coal wagon, a washstand, a fire escape, and a hospital bed.

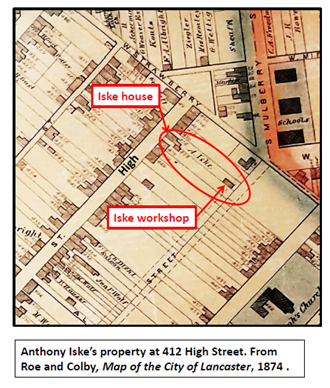

In 1860, Anthony built a frame house on a lot at 452 High, and lived and worked there for six years. When he moved out, the house he built was replaced by the new owner with a larger brick house that is now 450 High. In 1866, he bought a house on a lot at 412 High, where he and his family lived for 15 years (see 1874 map). He built a workshop at the end of his backyard, where he worked on his furniture and inventions. The house at 412 High still stands, although the workshop has been replaced by a house facing West Vine.

Anthony’s time at 412 High was very productive. He was granted several dozen patents for a cigar press, a reclining chair, a meat slicer, and numerous other devices. In the late 1870s, his son Albert, who showed a similar aptitude, began working alongside his father, and Albert’s name began appearing on patents in addition to his father’s.

By the 1870s, Anthony held dozens of patents, and had numerous other ones in progress. Keeping track of the status of each, and managing the required financial obligations among investors, lawyers, agents, salesmen, and manufacturers was challenging. Anthony frequently was called to civil court to defend himself against charges that he had not properly paid one party or another. In 1879, amid several simultaneous lawsuits involving patent and payment disputes, he was forced to sell his lot, house, and workshop at 412 High to help pay off his debts.

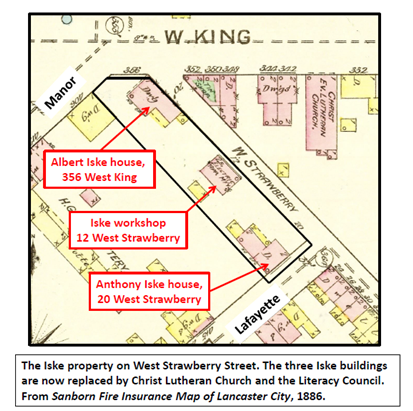

The Iske family soon bounced back. In March 1881, Anthony purchased a property along the first block of West Strawberry, extending from Manor to Lafayette. The property contained an old 1-1/2-story brick house on its northwest end facing West King, across from the Plow Tavern. The deed of sale was actually in the name of his son Albert, probably because of Anthony’s recent financial troubles.

Within a year, Anthony and Albert had built two additional buildings on the West Strawberry lot—a 2-1/2-story brick workshop (12 West Strawberry) in the middle of the lot, and a 2-1/2-story brick house (20 West Strawberry) on the southeast end of the lot (see 1886 map). Albert and his young family moved into the old brick house (356 West King) on the northwest end of the lot. Anthony and Felicite moved into the new house on the other end of the lot. The workshop was between the two houses, and through the 1880s, Anthony and Albert collaborated there on many patents, including ones for a heat motor, a fire ladder, and a combination hay rake and tedder.

In August of 1889, the Iskes sold the northwest part of the lot, where Albert’s house at 356 West King was located, to Christ Lutheran Church for its new church building. Albert and his family had to move into the upper floors of the workshop at 12 West Strawberry. Inventions continued rolling out of the Iske workshop at a steady pace, including a doorbell, a trolley fender, a trolley repair wagon, and an elevator.

Albert’s family continued growing, with several more children arriving by 1896, and soon the workshop and the rooms above it at 12 West Strawberry were no longer big enough. The Iskes enlarged the workshop into a double 3-story building, the larger side (10) of which was for Albert’s family and the smaller side (12) of which was for the workshop.

Unfortunately, the Iskes soon ran into financial difficulties again. In September 1897, they had to sell their remaining property along West Strawberry. Fortunately, the new owner of the property rented the houses and workshop back to the Iskes to use, and Anthony and Albert continued to work on inventions there, but the flow of inventions was slowing down. Only a handful proceeded to the patent phase, two of which were a reversible window sash and an intermittent motor.

Anthony’s wife, Felicite, died in August 1898. Anthony’s daughter Emma married George Heim in 1900, and the newly married couple purchased back the former Iske house at 20 West Strawberry, allowing Anthony to board there with them. In September 1906, the double 3-story house and workshop at 10 West Strawberry was sold to Christ Lutheran Church. Albert and his family rented back the house and workshop from the church until 1910 and then moved as tenants to 644 Fourth Street.

With the workshop now closed, Anthony retired from active inventing. While in his 70s and 80s, he continued tinkering at 20 West Strawberry, mostly trying to develop his heat motors into perpetual-motion machines. Anthony fell down the basement stairs at 20 West Strawberry in early January 1920, and died from internal injuries 10 days later, virtually penniless.

If Anthony Iske had been only an inventor, his life would still be noteworthy. But he did not just seclude himself in his workshop. He was a member of St. Joseph Church for more than 65 years, and sang in the choir there for 50 years. He served as the first President of Lancaster’s German Democratic Club, and President of the Schiller Death Beneficial Society for more than 30 years. He helped found the Fulton Death Beneficial Association and served as its President for seven years. He represented the Eighth Ward on the Town Council of Lancaster, and also on the Select Council. In addition, he served as a School Director, and was a member of the Lancaster Liederkranz and the Germania Turn-Verein.

Iske was described in an 1894 biographical portrait as a man who “bears a high reputation among his fellow-townsmen for honesty of purpose and straightforward conduct in everything he undertakes”. Arriving in Lancaster by mistake, he certainly made the most of his accidental home. Although he never became rich, Anthony Iske’s remarkable life is a testament to the importance of immigrants to the vitality and success of the Hill and the rest of Lancaster.

Notes: This piece was researched and written with the input of Gail Dowle, who lives in Wales in the United Kingdom. Gail is the great-great-granddaughter of Anthony Iske. The full story of Anthony Iske’s life and inventions will be published later this year in The Journal of Lancaster County’s Historical Society.