Jim Gerhart, August 2020

Oscar Shane’s pigeon arrived at its loft behind the Shane house at 608 High Street at 4:44 p.m. on June 10, 1908. The pigeon had been released, along with fellow competing pigeons, in Concord, North Carolina, at 5:10 that morning. It had averaged almost 35 miles per hour over its 400-mile journey back to Lancaster, winning the competition arranged by the members of the Lancaster District of the International Federation of Homing Pigeon Fanciers (IFHPF).

The breeding, raising, training, and racing of homing pigeons became a popular hobby on Cabbage Hill in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The sport of pigeon racing had been imported from Europe in the 1860s, with most of the bred-for-speed and bred-for-homing-ability pigeons coming from Belgium. In the U.S., it first blossomed in the big East Coast cities of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, but by the 1880s pigeon racing had found its way to Lancaster.

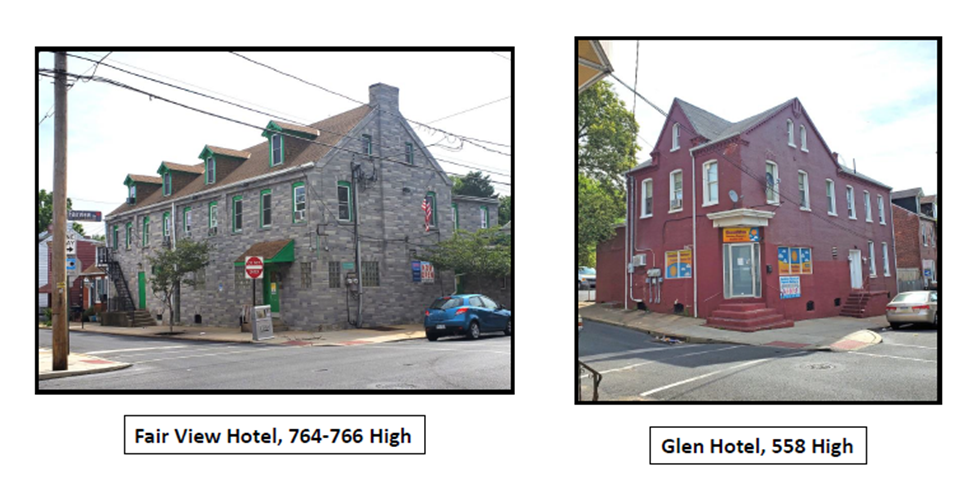

Article about the formation of the first homing pigeon club in

Lancaster, The Lancaster Examiner, February 20, 1889.

The first organized group of homing-pigeon owners in Lancaster was established in early 1889. It was called the Lancaster Homing Pigeon Club and it was made up of nine members owning some 200 pigeons. By the early 1890s, at least several pigeon owners from Cabbage Hill had joined the club—the aforementioned Oscar Shane (556 Manor), William Paulsen (560 Manor, the author’s great grandfather), and Adam Danz (606 High). In 1894, a second racing club was formed, the Hillside Homing Pigeon Club, possibly named so because it was headquartered on the Hill.

How did pigeon racing work? The clubs organized races on weekends during the spring, summer, and fall, with the participating members shipping their pigeons in crates by train to wherever the starting point of the race was. Most of the starting points were southward, usually in Virginia or the Carolinas. Each racing pigeon would have a metal band on one of its legs inscribed with the owner’s initials and a unique identifying number. At a designated time, usually in the early morning, all the pigeon contestants would be released and the trek home to Lancaster would begin. The pigeons would use their acute sense of smell and their uncanny ability to discern minute differences in the Earth’s magnetic field to find their way home to where they knew they would be fed and reunited with their mates.

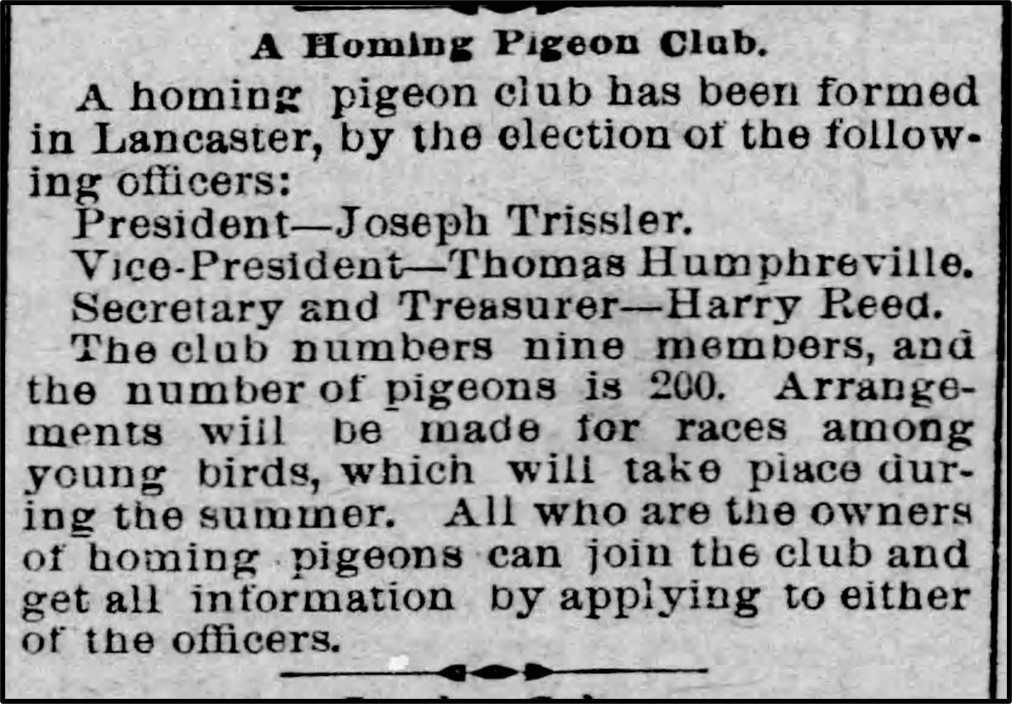

Results of a race of the Red Rose District of the IFHPF, in The Intelligencer

Journal, May 18, 1908. The average speeds are given in yards per minute.

Back in Lancaster, an official judge would be stationed at each loft where a competitor made its home, ready to read off from synchronized clocks the exact time at which each pigeon would alight at the door to its loft. The judges would then compare the times, and award a prize to the owner of the winner and runners-up. The prizes were often of significant value, and an owner with an especially accurate and fast-flying pigeon could offset the expense of his hobby.

But it was not always easy or pleasant for the pigeons. Often, some would not make it home, especially when flying through bad weather. In one particularly bad storm in 1911, only 15 of 73 pigeons made it home to Lancaster within four days of being released in Newberry, South Carolina. Others would finally arrive long after the race was over. For example, in at least two extreme cases, Hill pigeons returned nearly two years after their release.

On the other hand, there were some feel-good stories as well—for example, after one loft owner’s death, his many pigeons were sold to a place in New York for butchering. A few days after their arrival in New York, two of the condemned pigeons were found back at their original loft, “strutting around the old coop, contented and cooing”, having escaped and found their way home. One hopes double jeopardy ensured them a long happy life.

Perhaps the high tide of early pigeon racing in Lancaster occurred in the latter part of the first decade of the twentieth century. In 1908, there were three clubs in Lancaster, each with at least ten members and many hundreds of pigeons. The Lancaster District of the IFHPF, with about half its members being from Cabbage Hill, and the Red Rose District of the IFHPF, with nearly all of its members being from the Hill, were two of the clubs. The third club was the Keystone Homing Pigeon Club, which was not affiliated with the IFHPF and which had no members from the Hill.

To give an idea of the makeup of these clubs, here are nine Cabbage Hill members of the Red Rose District, with their 1907 addresses:

Gustavus F. Lutz 529 High

Herbert J. Henkel 436 West Vine

Henry P. Keller 636 Lafayette

William Paulsen 560 Manor

Elias E. Herr 638 Lafayette

Charles J. Fritsch 812 High

Adam J. Danz 826 St. Joseph

Philip Etter 725 High

Otto Hecht 530 Lafayette

Of these nine club members, six of them lived on High and Lafayette. Their average age was about 35, and all of them were tradesmen, with six of them working in the cigar industry. Only two of them had been born in Germany, but the majority of them were sons of German immigrants.

In the decade from 1910-1920, which included World War I, the Red Rose District of the IFHPF continued to actively compete. Even during the war, the club continued racing, but the number of Hill members dwindled to just four—Oscar Shane (657 High), Charles J. Schill (618 West Vine), Frank Wechock (420 High), and Frank Martin (710 St. Joseph). Perhaps this had something to do with the members of German heritage wanting to avoid the spotlight during the intense anti-German sentiment directed at Cabbage Hill during the war.

In 1917, Red Rose member Charles Schill was elected Secretary of the entire IFHPF, and in his official capacity he was asked by the Army to provide an inventory of all the homing pigeons affiliated with the IFHPF. The inventory was essentially a draft registration for homing pigeons, because there was a need for their service at the European war front. The pigeons were expected to be “doing a bit as a patriot, to help our country in this great crisis.” In fact, in May 1918, General Pershing directed 3,000 homing pigeons and 100 trained handlers to be dispatched to the European front.

A dispatch rider taking homing pigeons to the

trenches in WWI, The Inquirer, May 18, 1918.

Once at the front, homing pigeons were used to deliver messages back from the front lines. As a 1918 newspaper article noted, “They did work which the wireless, telegraph and telephone could not do under certain conditions.” Homing pigeons with rolled messages in containers banded to their legs would circle up from the trenches, dodge through the shells, bullets, and poison gas, and deliver their messages to military headquarters miles behind the battle lines. They were said to have a 97% success rate, and there was at least one pigeon who was hit by German fire and still was able to deliver its message.

Back on Cabbage Hill after the war, pigeon racing continued for many years. As just one example, Charles Schill, the Secretary of the IFHPF during WWI, went on to own race-winning homing pigeons well into the 1940s. However, about ten years ago, due to complaints of unsanitary conditions in backyard lofts, Lancaster was forced to ban the keeping of pigeons within the city limits. That ended more than 100 years of the homing-pigeon sport in the city, but many rural clubs still exist, and a large national network of racing aficionados still compete in much the same way as before.

Today, if you stop on Cabbage Hill and listen carefully, especially around High and Lafayette, you might be able to pick up the last echoing coos from the golden age of homing-pigeon racing on the Hill.