This article is part of a series of posts from SoWe Volunteer Historian Jim Gerhart about the stories behind the stores on Old Cabbage Hill.

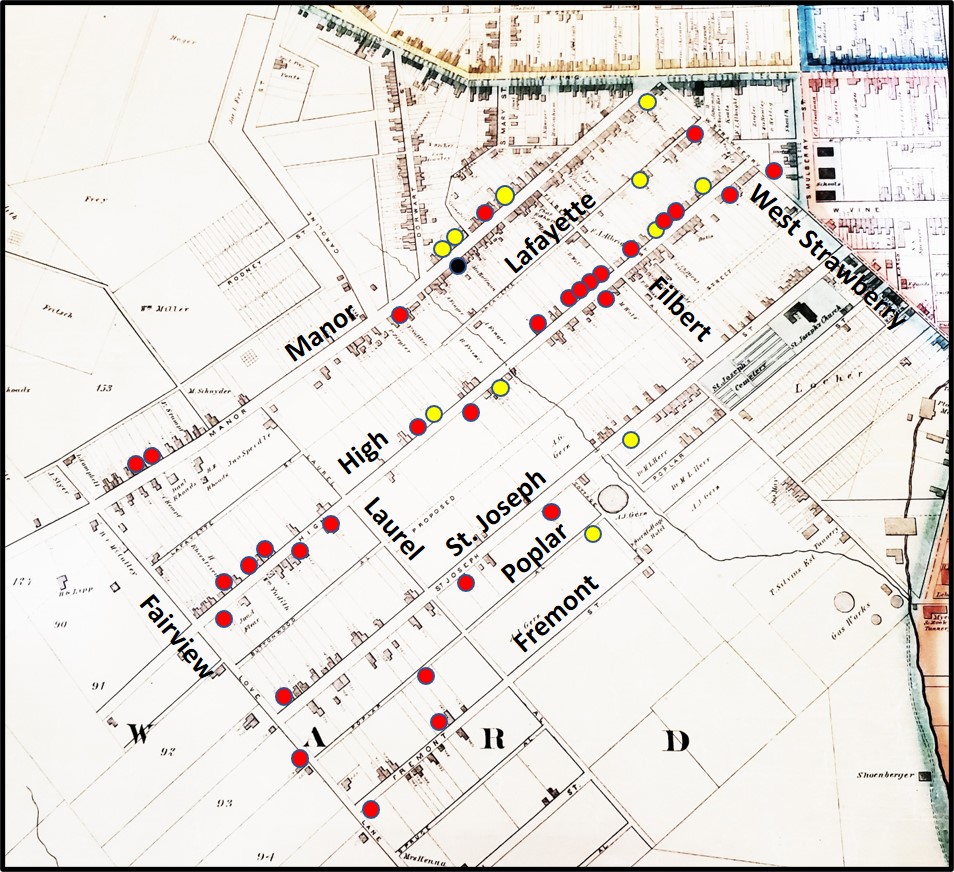

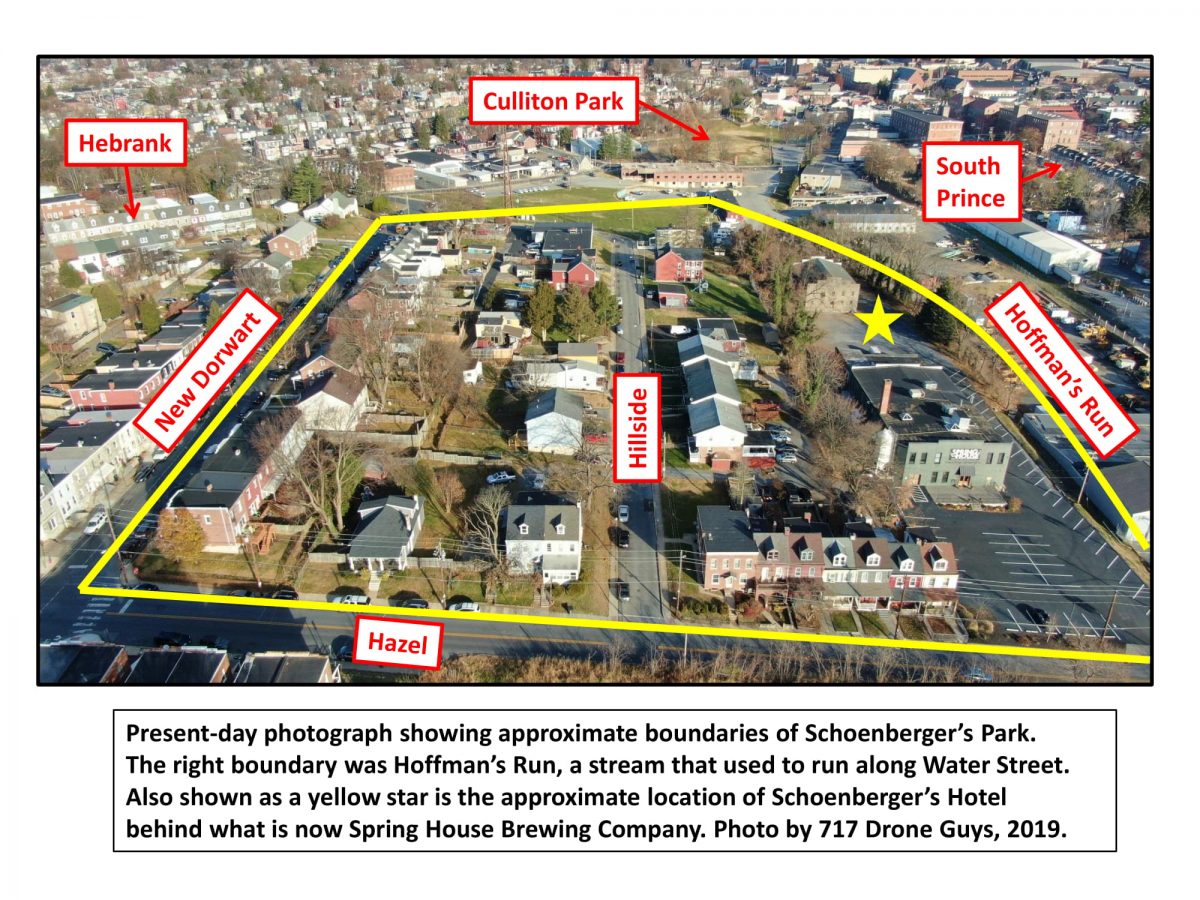

The origin of the corner store at 23 New Dorwart Street, which most people will remember as King’s Confectionery, begins with the building of a sewer. In the early 1880s, a small stream called the Run, which ran along what is now New Dorwart, was diverted into an arched brick sewer buried beneath the street. This opened the door for further building of houses along New Dorwart, and within a couple of decades, the street would be fully built out.

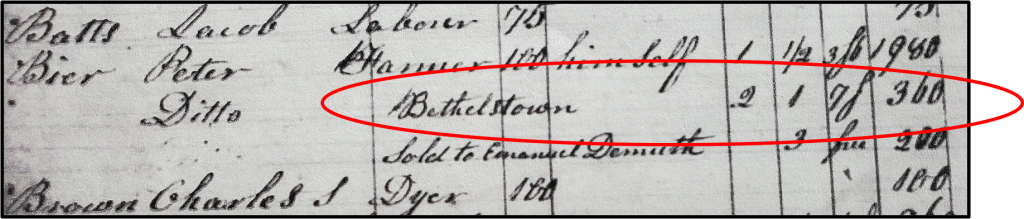

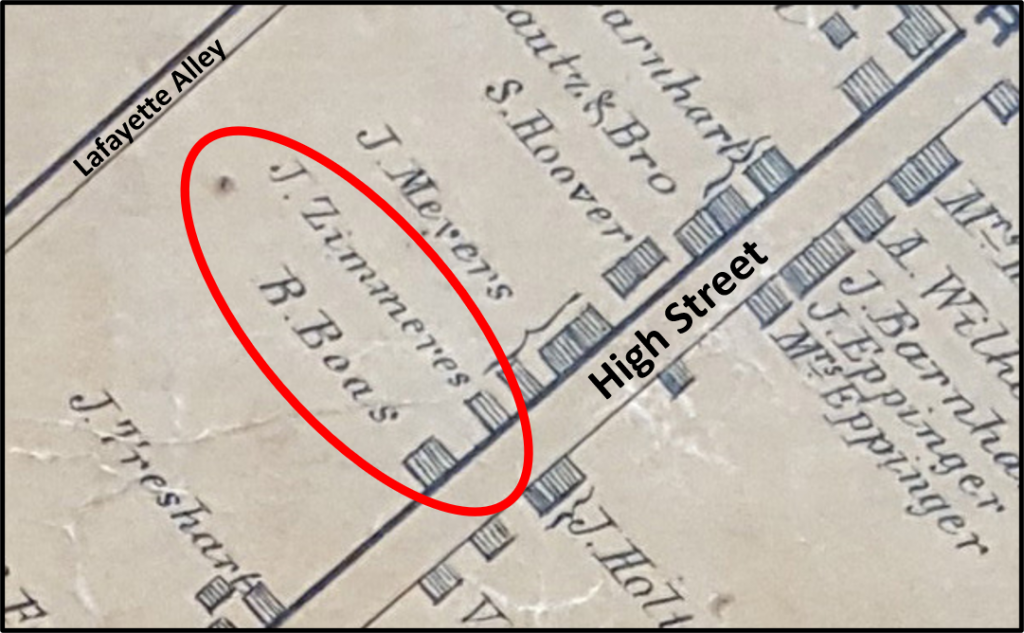

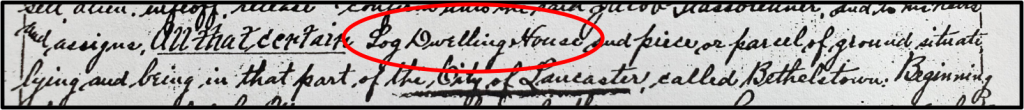

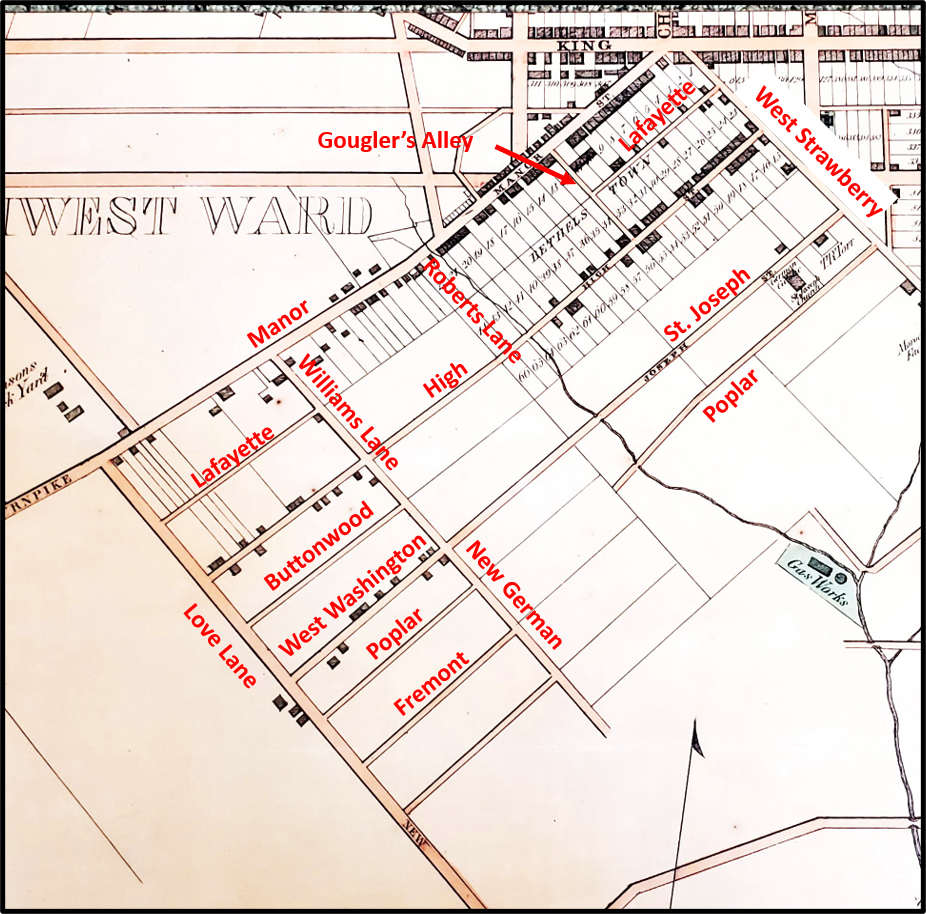

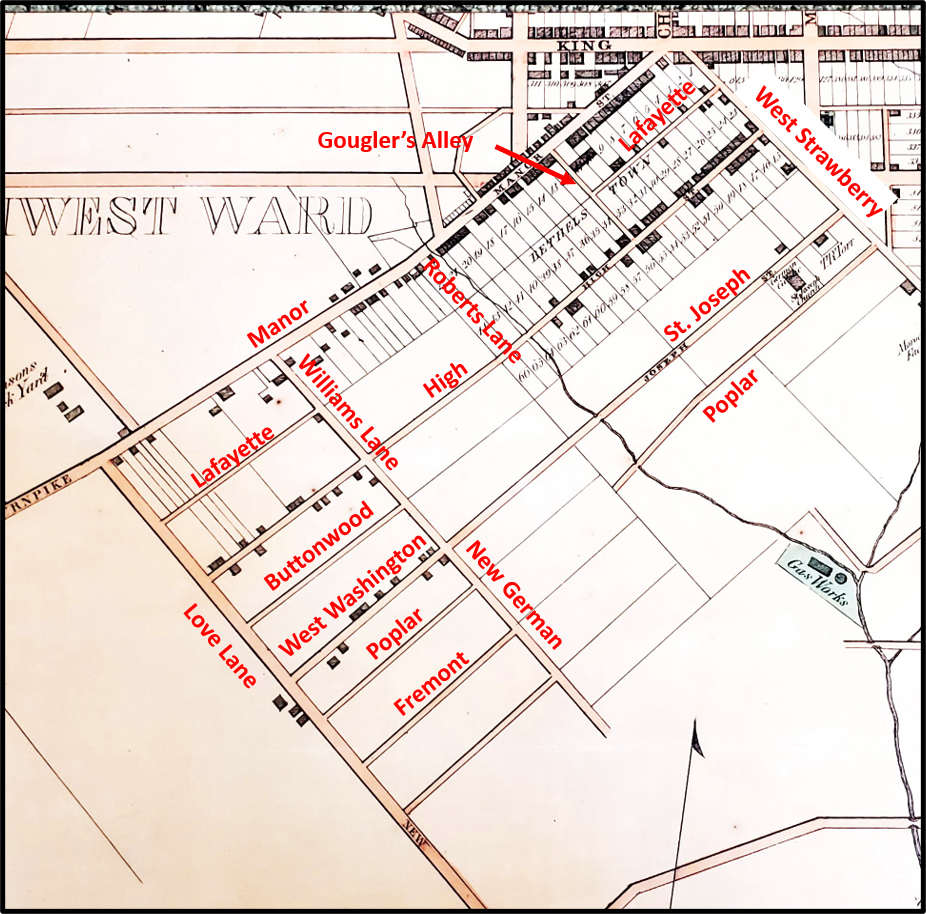

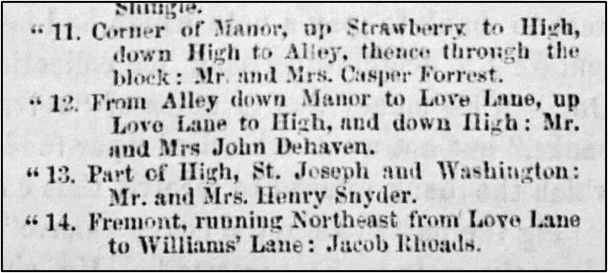

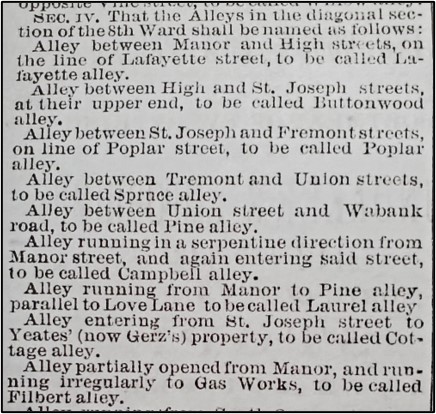

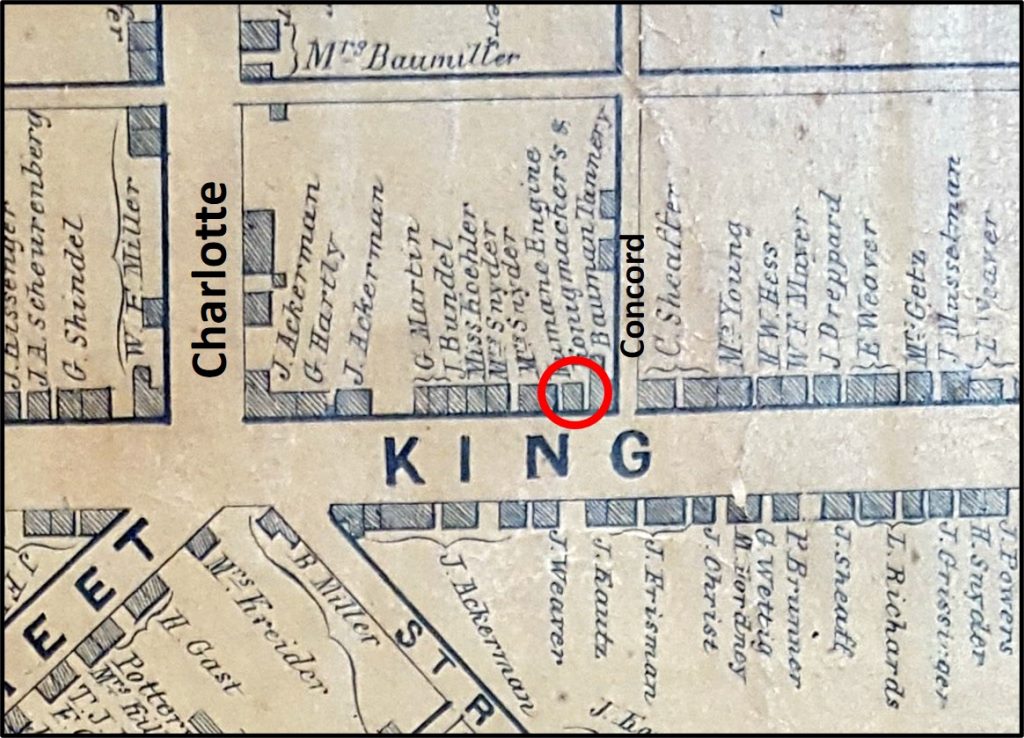

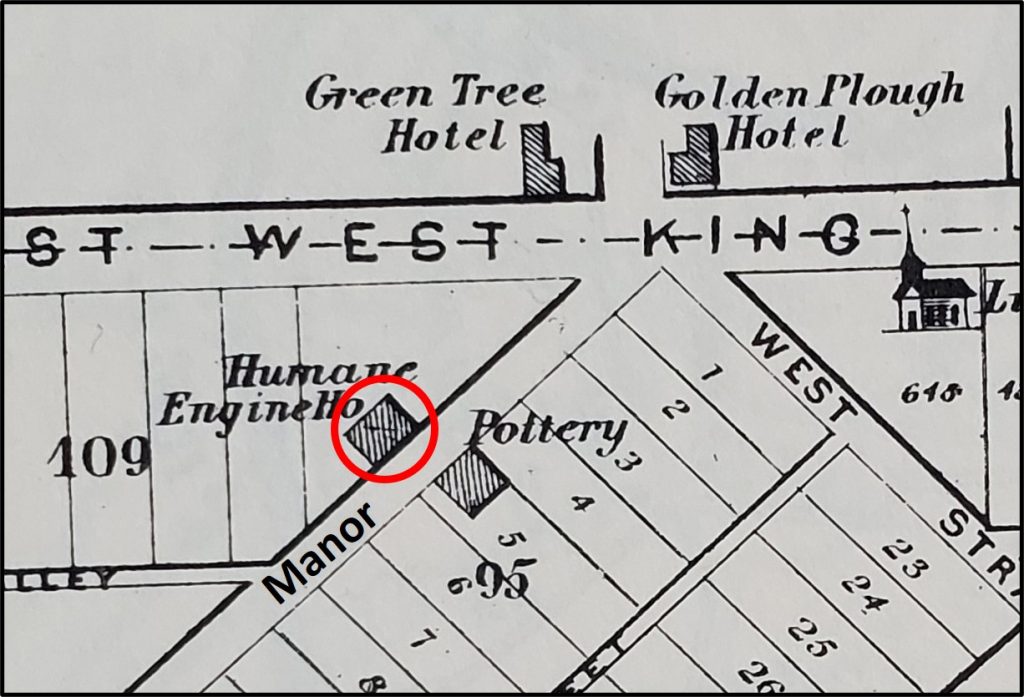

Before the sewer was installed, the empty lot on which 23 New Dorwart would be built was owned by Adam Finger. Finger was a wealthy, German-immigrant grocer and landlord who operated the grocery store at 568 Manor, and owned various other properties in the vicinity. In 1892, Finger sold a twenty-foot strip of his land between Lafayette and High to the city so that South Dorwart could be widened on its northeast side so that houses could be built (New Dorwart was named South Dorwart in its early years).

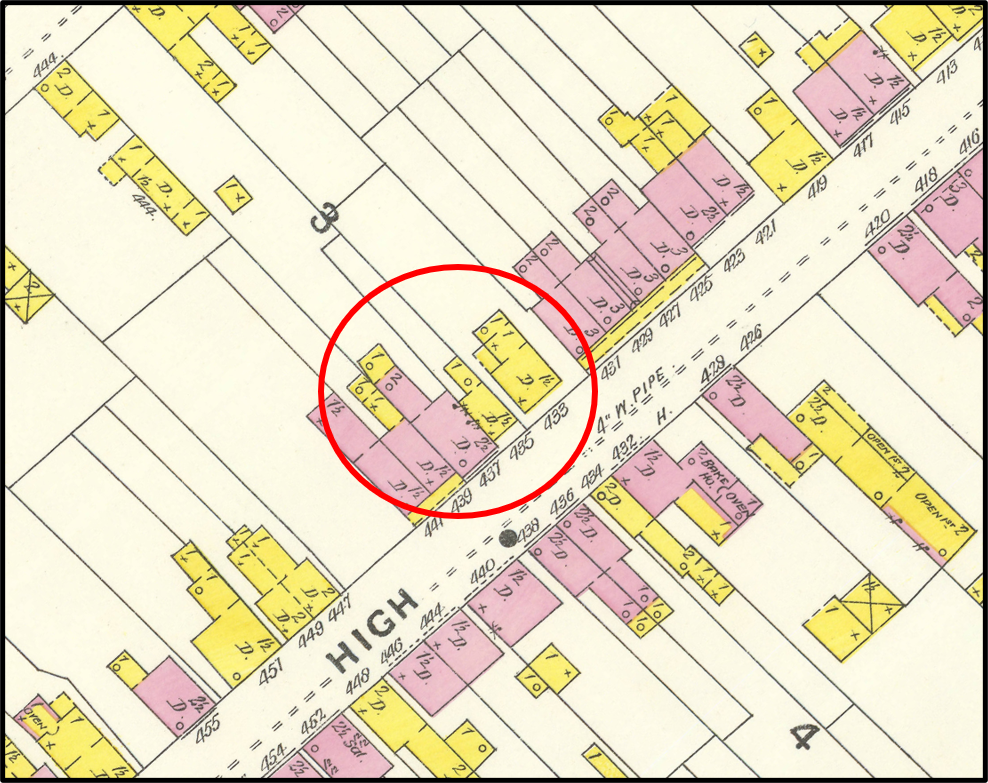

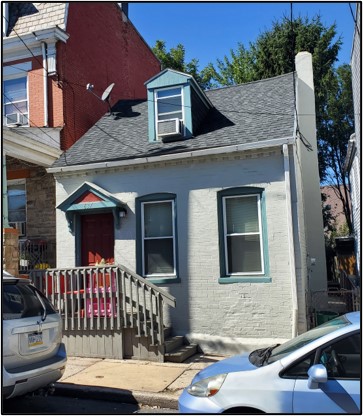

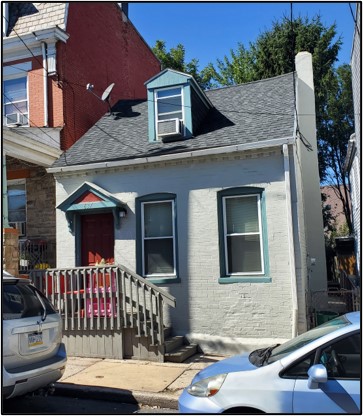

Finger sold his land along New Dorwart between Lafayette and High to the Home Building & Loan Association in 1894. The HBLA, a development company, built the row of twelve two-and-a-half-story houses on the northeast side of New Dorwart in the mid-1890s. The house at 23 New Dorwart was located on a lot with sixteen feet of frontage on New Dorwart, extending eighty-three feet along Lafayette. It had a store on its first floor and a residence on its second floor. There were six rooms, a bathroom, and a two-story frame back building. Later, two other houses would be built on the lot along Lafayette.

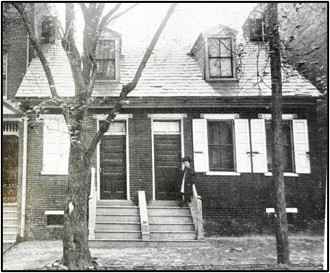

There was a storefront for the first-floor store, much of which remains today. The doorway to the store was canted at forty-five degrees to face the intersection. Facing New Dorwart, there was a large display window with transoms above it, which remains today. Separating the storefront from the residence above was a cornice that also remains. Old maps indicate that for most of the first half of the twentieth century, there was a wooden frame with an awning that extended on both sides of the entrance, overhanging the sidewalk in front of the store.

In 1899, the HBLA sold the house and store it had built on the corner of New Dorwart and Lafayette to John B. Funk for $1,375. Funk also ran a grocery store at 401 West Walnut that he called Model Cash Grocery. In 1899, he opened a new branch of his West Walnut grocery in the building he had just bought at 23 New Dorwart. Funk enlisted his twenty-five-year-old son, Clifford A. Funk, to run the new branch store. Clifford continued living at home on West Walnut while running the new branch of Model Cash Grocery at 23 New Dorwart.

In 1903, John Funk sold his branch store on New Dorwart to Jacob Kohr, who eighteen months later, sold it to John W. Wenger for $2,200. Wenger opened his own grocery in the store, and operated it until 1910, when he sold it to William P. Ostermayer for $2,800. Ostermayer moved his family into the second floor of the building and ran a grocery in the store for about five years. Ostermayer went bankrupt and in early 1916, the Union Trust Company purchased the store for $4,110.

The store was vacant for a couple of years, but then Union Trust Company leased it to Lena Ansel and her daughter Pearl, who opened L & PS Ansel Grocery in the store. Lena was the fifty-five-year-old wife of Lazarus Ansel, a clothier. Lazarus and Lena were both Russian immigrants who lived on Hebrank. The Ansels ran their grocery for a couple of years, but in 1922, the Union Trust Company sold the store to Walter D. King for $4,200.

Walter King, who had served in the Army in WWI, opened King’s Confectionery in the store. He later added a restaurant to the candy store. King’s would be in business for the next seventy years, and become a favorite in the close-knit Cabbage Hill community. King was twenty-six when he opened the store, and he operated it until his death forty years later. King and his family lived above the store, and then in the house facing Lafayette behind the store. After King’s death, his widowed third wife, Pauline, some twenty-five years younger than him, sold the store to Harry R. Martin for $18,000.

Martin, a WWII veteran who ran a similar store at 401 East King, would retain the name of King’s Confectionery for his store at 23 New Dorwart, and would own the store until his death in 1990. Martin covered the building’s brick with form-stone and rented the second floor to tenants. When Martin died, his wife Marion sold the store to BJ Properties, a property management company and landlord, for $70,000.

In 1993, BJ Properties leased the store to three brothers—Jim, George, and Leo Bournelis—who opened a restaurant they named The Steak-Out, and later Steak Attack, which they ran in the store into the late 1990s.

Next, BJ Properties leased the store to LeGrant Williams, who opened Premier Cuts and Styling, a men’s barbershop. In 2002, Williams bought the store from BJ Properties. In 2016, Williams sold the store, and now two owners later, it remains a barbershop, but now it is known as Century 21 Cuts.