Jim Gerhart, April 2020

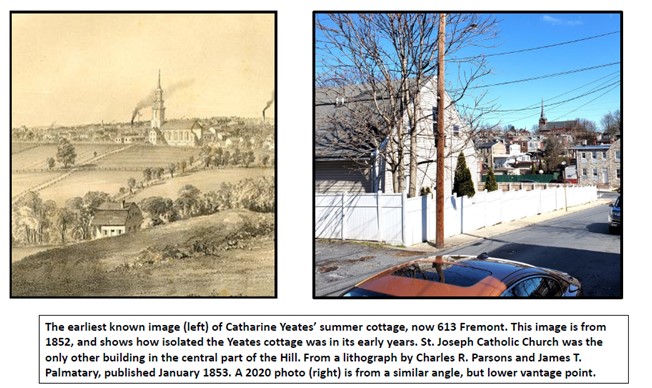

There’s a good chance you have walked or driven by the three-unit apartment house at 613 Fremont Street without thinking twice about it. It’s really not much more remarkable than other nearby houses, except that the lot is larger than most and there is a privacy fence around it. But the house has a long remarkable history. In fact, it was the first house built in the central part of Cabbage Hill.

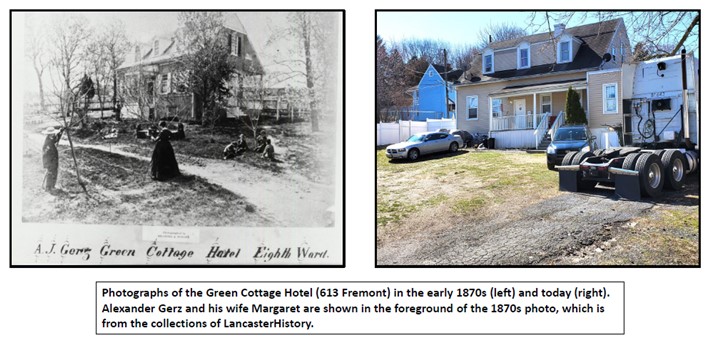

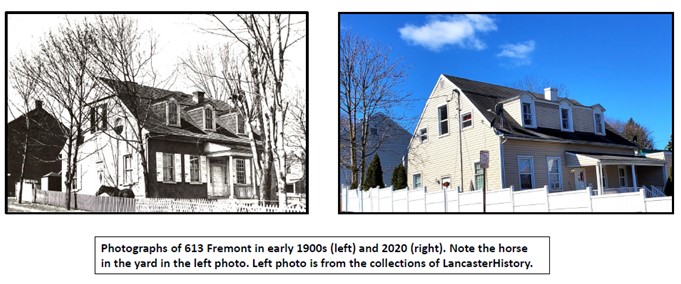

The two-story, frame house with a gambrel roof, now clad with modern siding, was built in 1838 as the summer cottage of Miss Catharine “Kitty” Yeates. The house has had many owners and tenants over the last 180 years. I will briefly trace its history here, with closer looks at two of its most interesting owners—Miss Yeates, a wealthy philanthropist, and Alexander J. Gerz, a Civil War veteran and entrepreneur.

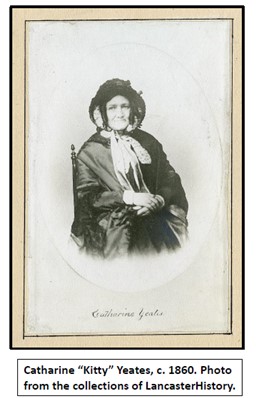

The house’s first owner, Catharine Yeates (1783-1866), was the daughter of Jasper Yeates, a famous Lancaster lawyer and State Supreme Court Justice. Starting in 1820, after she had inherited part of her father’s considerable estate, Catharine bought several tracts of land in what is today the heart of Cabbage Hill. Her property totaled almost ten acres and, in terms of today’s streets, was centered on the 500 blocks, and part of the 600 blocks, of St. Joseph, Poplar, and Fremont.

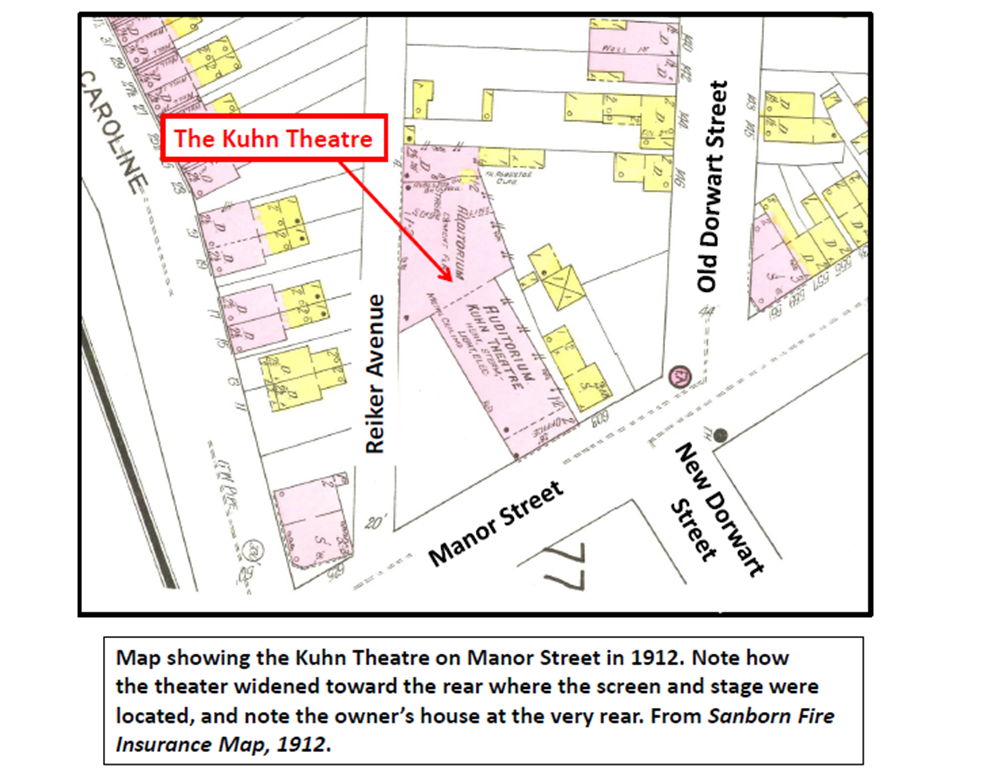

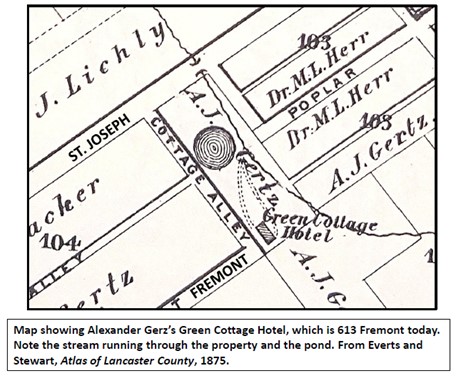

In 1838, Catharine built her summer cottage (now 613 Fremont) on the southernmost corner of her property. At that time, there were no other houses in the area, and there were no streets, only tree-lined dirt paths separating fenced pastures. A stream starting near Manor Street and ending at South Water Street, ran in front of her house. The setting was perfect for what she wanted—a cool place where she could escape from her family’s mansion on South Queen Street near the square when the summer heat and city life got too oppressive.

Catharine, who never married, lived in her cottage during the summers for the next fifteen years. She sometimes rented out rooms on the second floor to various tenants. The property required maintenance, and she had a caretaker to tend to the lawn and flower beds, the fruit trees and grapevines, and the fenced pastures where her horses and cattle were kept. The stream in front of her house, which flowed where New Dorwart is today, supplied her house, livestock, and chickens with water.

In 1855, Catharine deeded the cottage and all of its surrounding acreage to her nephew Jasper Yeates Conyngham. Catharine died in 1866, and in her obituary in a Lancaster newspaper, she was praised as “…one of the most estimable ladies that ever resided in the city…” Perhaps her most consequential act of philanthropy was the founding and endowment of the Yeates Institute, a private school in Lancaster intended to prepare students for the Episcopal ministry.

Catharine’s nephew Conyngham did not live in the cottage, renting it out instead. In 1869, he sold the house and its property to David Hartman, who was a city tax collector and wealthy real-estate investor. Hartman later was elected county sheriff. He bought the Yeates property as an investment for $5,500, and sold it the following year to Alexander J. Gerz for $7,000.

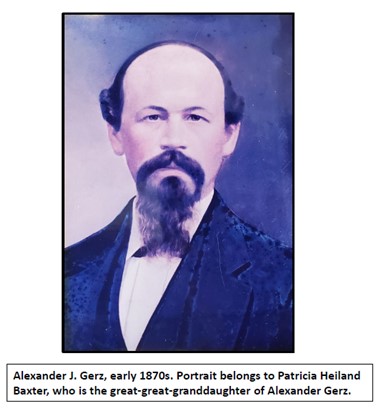

Gerz (1826-1876) was an immigrant from Lorraine, near the border of France and Germany, who was part of a successful family pottery business in Lancaster. He enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War, serving in the 79th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers. Shortly after returning from the war to Lancaster, he moved with his wife to Mexico, where he enjoyed success in the pottery business there. He was forced to leave Mexico during a revolution, and enroute back to Lancaster, his wife died of yellow fever in New Orleans. Back in Lancaster, he resumed his pottery business, ran the Eagle Hotel on North Queen, remarried, and had four children.

In 1870, Gerz bought the former Yeates property, where he opened a hotel and saloon in the summer cottage, calling it the Green Cottage Hotel. He held events on the property, including dance parties and reunions for his fellow Civil War veterans. The one-acre lawn around the hotel and saloon consisted of well-kept grass, flower gardens, and fruit and shade trees. Next to the hotel on the northwest side was a large pond stocked with a wide variety of fish. (The site of the pond was an abandoned, short-lived quarry that Gerz had dug when he discovered marble under his property in 1870.) Also on the grounds were a small deer park and a large wooden platform (thirty-two feet square) for dancing. The grounds could be accessed by a bridge over the stream that ran in front of the hotel.

Gerz died at the age of fifty in 1876. His widow, Margaret, sold his remaining property, including the cottage, at auction in November 1878. Henry Haverstick bought the cottage property for $2,100. For the sale, the lot on which the cottage was located was reduced in size to 200 feet square, bordering on New Dorwart and Fremont.

In 1884, Haverstick sold the property to John Snyder, who was a hotel proprietor and tobacco merchant. The Snyder family would own the property and live there for the next forty-five years, with son Michael Snyder taking over ownership when his father died in 1930. John Snyder built a tobacco warehouse on the opposite corner of the lot from the cottage, at the intersection of Poplar and New Dorwart.

A year after John Snyder’s death, his son Michael sold the property to Harry M. Stumpf. Stumpf was a building contractor and Michael Snyder’s cousin. He built garages on the property between the cottage and Poplar, and ran his contracting business from there. He converted the cottage into two apartments and rented them out. The Stumpf family was prominent on the Hill and in Lancaster for many years. Harry’s father, John, owned a hotel in the 400 block of Manor Street, and Harry’s brother, Edward, owned a service station and garage in the 500 block of Fremont, and also was the owner of Stumpf Field along the Fruitville Pike.

In 1952, Harry Stumpf sold the lot with the cottage to Samuel Lombardo for $15,000. Lombardo and his wife Elsie got divorced in 1956. Elsie got the cottage, remarried to Maurice Brady, and lived in the cottage until her death in 1991. Elsie and Maurice added a third apartment to the house, living in the main apartment themselves and renting out the other two. The house remains divided into three apartments to this day.

To be sure, Miss Yeates’ 1838 summer cottage has changed a lot over the years. It no longer sits all by itself in the middle of pasture land. It doesn’t have a stream in its front yard. It has been added to and modified numerous times. But the basic structure of the cottage is still intact. The next time you pass the house at 613 Fremont, try to visualize it as it was 150 years ago, when it was a hotel and saloon surrounded by well-kept grounds that were home to a fish pond and a deer park. It’s just one more example of all the history hiding just below the surface on Cabbage Hill.