Coming this Fall – in partnership with Saint Joseph’s Catholic Club, SoWe will be hosting a 6-week Youth Bowling Club right here in the neighborhood (meaning no transportation needed). During these 6 weeks, up to 20 middle school kids will learn how to bowl* and how to keep score! Additionally, pizza will be provided during each session! However, before we open sign-ups for this wonderful, FREE, local sporting opportunity – we first need to find our volunteer leads (to ideally help all 6 weeks). We are looking for: · 2 Duckpin Bowling Instructors · 2 Duckpin Scoring Instructors · 4 Pin Reset-ers (these volunteers would need to get up and down staged platforms – as these pins do not automatically reset. Job best for teens/young adults. See second picture for reference)  This Club will happen this October through the beginning of November 2024. And depending on the volunteers – will happen on Saturdays (10AM – 12PM) OR Thursdays evenings (6-8PM). Please Note: You do not need to have prior Duckpin Bowling experience to be one of our instructors. However, we would cherish if one of our instructors was a past Cabbage Hill “roller.” If you are interested in any of the above volunteer roles – please email Jacquie at Jacquie@WeAreTenfold.org. Also, if you played in one of Cabbage Hill Leagues growing up, please also email Jacquie as we’d love to hear and re-retell some of your stories and/or have you as a consultant for our bowling instructors. *The Bowling Alley at Saint Joseph’s Catholic Club is for Duckpin Bowling. Duckpin bowling is a variation of standard 10-pin bowling with smaller and lighter bowling balls and shorter pins. This kind of bowling is rare (there are only about 50 active duckpin bowling alleys in the country) and a beloved part of our SoWe neighborhood’s history (in the past, leagues used to play in the Saint Joseph’s Club bowling alley 6 days a week). |

Category: Featured

Peace In The Streets Block Party

Mark your calendars for this year’s block party! Volunteers are need. You can sign up here.

SoWe Store Stories: 568 Manor Street, Philip Schum (1852)

The building at 568 Manor Street is one of the oldest surviving buildings on Manor Street, having been built in 1852. Like most old stores on Cabbage Hill, it holds a special place in the memory of today’s older Hillians, with many neighborhood old-timers fondly recalling it as the Manor Street 5&10. But it also has an interesting history that goes back way beyond living memory.

Philip Schum, a German immigrant, built the double, two-and-a-half-story, brick house on the southeast side of Manor Street, just across from where Old Dorwart Street intersected Manor from the west. New Dorwart Street would not be opened for another few decades; instead, a stream ran past Schum’s new house, in the middle of what would later become New Dorwart. The double house had two front doors and was divided into two houses by a wall running through the middle of the building. The address of the house, according to the 1857 directory, was “Manor nr the Bridge”, referring to the bridge that had been built to carry Manor Street over the stream.

Schum ran a grocery store out of his new house, and soon added coverlets he made to his store inventory. The coverlets turned out to be very popular, so much so that he soon moved his store to Water Street, and focused exclusively on coverlets, becoming a wealthy, successful merchant. Schum and his wife would be killed near Salunga in 1880 when their carriage was hit by a train.

In 1857, when Schum moved to Water Street, he sold the double brick house on Manor to Jacob Shindel, the son of his neighbor, Peter Shindel, who lived in a log house along the stream next to Schum’s property. Jacob Shindel then sold the house to Adam Finger, a German immigrant, in 1860, for $3,000. Finger, his wife, and their four children lived on the second floor, and ran a grocery and dry goods store on the first floor of one side of the building. Over the forty years that Finger lived and worked there, he added more store and storage space to the rear of the house. He also sold the back of his lot for the building of houses facing New Dorwart in the 1880s, and then sold the land he owned on the northeast side of the next block of New Dorwart for more houses in the 1890s.

After Finger’s death, his son Philip sold the house and store to Philip Fellman for $2,500. Fellman and his brother Louis ran a hardware store out of the first floor, and lived above it. In the 1910s, the Fellmans added a three-story brick shop and warehouse behind the house along New Dorwart, where they added metal-working to their resume. For a brief spell in 1922-24, the store was leased to S.S.S. Stores of New York City.

In 1934, the house and store, as well as the warehouse and shop behind it, were sold for $2,705 at a Sheriff’s sale to Leonard Horst of Philadelphia. Horst never came to Lancaster but leased the store to American Stores Co, Inc., a grocery chain, and rented out the second floor as a residence.

In 1944, after Horst’s death, Joseph Martin of Dauphin County bought the property for $6,500. Martin also was a landlord who continued to lease the store, this time to Acme Supermarkets, renting out the second-floor residence. Martin also converted the warehouse and shop behind the house into apartments, which they have been since.

In the late 1940s, Martin leased the store as the Manor Street 5&10 Cents Store, which it remained into the mid-1970s. The store advertised frequently in the local newspapers, especially for special sales for Christmas, Easter, Fourth of July, and Back-To-School days. In 1970, a fire in the attic was extinguished by the city fire department before any significant smoke or water damage could occur.

Santos Rodriguez bought the house, store, and apartment building in 1972 for $12,500. He completely renovated the apartments over a couple of years and then in 1976 sold the property to Charles Rettew of Lititz for $45,000. Rettew flipped the property that same year for $57,500, selling it to Michael Mastros of Lancaster. Mastros continued leasing the store and renting the apartments until he died in 2012 in a car accident.

For several years starting in the mid-1970s, the store was occupied by Playland and then Denny’s Game Room. The store was vacant throughout most of the 1980s. From 1991 to 2007, the store was occupied by De Jesus Mini Market, and from 2008 to 2011, J&A Mini Market. For the last twelve years, Sunshine Market has operated out of the store. The second floor and three-story rear attachment are still rented as apartments. The nearly 175-year-old building at 568 Manor has seen several modifications and additions. It started as a double house, serving as a store and residence, which it was until the first few years of the 1900s. At that point, the entire first floor was reconfigured as a store with a storefront, including two five-by-twelve-foot show windows (now covered); a cornice that spanned the entire front of the store, supported by large brick columns; and a recessed entrance. Added to the rear, also in the 1910s, was a three-story warehouse and shop that has been an apartment building for the last one hundred years. It started out as a house and store on a dirt road near a bridge over a stream, and ended up as the home of some of the key businesses in “downtown” Cabbage Hill.

Support SoWe During ExtraGive

If you’re participating in this year’s ExtraGive, please consider including SoWe in your giving. Your support helps your neighbors and our neighborhood! We use donations to:

- Fund several neighborhood events every year, including our Earth Day Celebration, Annual Block Party, and our Halloween Trick or Treat. These events connect neighbors to each other and give us a chance to celebrate our wonderful neighborhood!

- Support low-income homeowners with grants to make critical repairs to their homes. Our Affordable Home Repair Program helps our neighbors maintain safe, quality housing.

- Keep our parks clean through our partnership with Lancaster County Food Hub’s Hand Up Partners Initiative. This project provides stipends to our homeless neighbors to clean Culliton and Brandon Parks, providing both critical support to neighbors and ensuring our parks are able to be enjoyed by SoWe families and households!

You can donate directly to SoWe on November 17th using this link.

SoWe Food Box Giveaway

SoWe Store Stories: 23 New Dorwart St., John Funk (1899)

This article is part of a series of posts from SoWe Volunteer Historian Jim Gerhart about the stories behind the stores on Old Cabbage Hill.

The origin of the corner store at 23 New Dorwart Street, which most people will remember as King’s Confectionery, begins with the building of a sewer. In the early 1880s, a small stream called the Run, which ran along what is now New Dorwart, was diverted into an arched brick sewer buried beneath the street. This opened the door for further building of houses along New Dorwart, and within a couple of decades, the street would be fully built out.

Before the sewer was installed, the empty lot on which 23 New Dorwart would be built was owned by Adam Finger. Finger was a wealthy, German-immigrant grocer and landlord who operated the grocery store at 568 Manor, and owned various other properties in the vicinity. In 1892, Finger sold a twenty-foot strip of his land between Lafayette and High to the city so that South Dorwart could be widened on its northeast side so that houses could be built (New Dorwart was named South Dorwart in its early years).

Finger sold his land along New Dorwart between Lafayette and High to the Home Building & Loan Association in 1894. The HBLA, a development company, built the row of twelve two-and-a-half-story houses on the northeast side of New Dorwart in the mid-1890s. The house at 23 New Dorwart was located on a lot with sixteen feet of frontage on New Dorwart, extending eighty-three feet along Lafayette. It had a store on its first floor and a residence on its second floor. There were six rooms, a bathroom, and a two-story frame back building. Later, two other houses would be built on the lot along Lafayette.

There was a storefront for the first-floor store, much of which remains today. The doorway to the store was canted at forty-five degrees to face the intersection. Facing New Dorwart, there was a large display window with transoms above it, which remains today. Separating the storefront from the residence above was a cornice that also remains. Old maps indicate that for most of the first half of the twentieth century, there was a wooden frame with an awning that extended on both sides of the entrance, overhanging the sidewalk in front of the store.

In 1899, the HBLA sold the house and store it had built on the corner of New Dorwart and Lafayette to John B. Funk for $1,375. Funk also ran a grocery store at 401 West Walnut that he called Model Cash Grocery. In 1899, he opened a new branch of his West Walnut grocery in the building he had just bought at 23 New Dorwart. Funk enlisted his twenty-five-year-old son, Clifford A. Funk, to run the new branch store. Clifford continued living at home on West Walnut while running the new branch of Model Cash Grocery at 23 New Dorwart.

In 1903, John Funk sold his branch store on New Dorwart to Jacob Kohr, who eighteen months later, sold it to John W. Wenger for $2,200. Wenger opened his own grocery in the store, and operated it until 1910, when he sold it to William P. Ostermayer for $2,800. Ostermayer moved his family into the second floor of the building and ran a grocery in the store for about five years. Ostermayer went bankrupt and in early 1916, the Union Trust Company purchased the store for $4,110.

The store was vacant for a couple of years, but then Union Trust Company leased it to Lena Ansel and her daughter Pearl, who opened L & PS Ansel Grocery in the store. Lena was the fifty-five-year-old wife of Lazarus Ansel, a clothier. Lazarus and Lena were both Russian immigrants who lived on Hebrank. The Ansels ran their grocery for a couple of years, but in 1922, the Union Trust Company sold the store to Walter D. King for $4,200.

Walter King, who had served in the Army in WWI, opened King’s Confectionery in the store. He later added a restaurant to the candy store. King’s would be in business for the next seventy years, and become a favorite in the close-knit Cabbage Hill community. King was twenty-six when he opened the store, and he operated it until his death forty years later. King and his family lived above the store, and then in the house facing Lafayette behind the store. After King’s death, his widowed third wife, Pauline, some twenty-five years younger than him, sold the store to Harry R. Martin for $18,000.

Martin, a WWII veteran who ran a similar store at 401 East King, would retain the name of King’s Confectionery for his store at 23 New Dorwart, and would own the store until his death in 1990. Martin covered the building’s brick with form-stone and rented the second floor to tenants. When Martin died, his wife Marion sold the store to BJ Properties, a property management company and landlord, for $70,000.

In 1993, BJ Properties leased the store to three brothers—Jim, George, and Leo Bournelis—who opened a restaurant they named The Steak-Out, and later Steak Attack, which they ran in the store into the late 1990s.

Next, BJ Properties leased the store to LeGrant Williams, who opened Premier Cuts and Styling, a men’s barbershop. In 2002, Williams bought the store from BJ Properties. In 2016, Williams sold the store, and now two owners later, it remains a barbershop, but now it is known as Century 21 Cuts.

SoWe Store Stories: 705 High Street, Abraham Ansel’s Grocery (1923)

This article is part of a series of posts from SoWe Volunteer Historian Jim Gerhart about the stories behind the stores on Old Cabbage Hill.

Not every store on Cabbage Hill was owned by German immigrants. The brick house and store at 705 High Street was built by a Russian immigrant of the Jewish faith.

Abraham Ansel arrived in Lancaster in 1880 and took up residence in the Southeast Ward where he began working as a junk dealer. He and his first wife Rebecca soon entered the grocery business at the corner of Mercer and Locust Streets. In 1908, Rebecca died at the age of forty-three, leaving Abraham with their young son Myer.

Abraham remarried and he and his second wife Sarah had five children. Following a tragic accident in their house in which their two-year-old child lost his life, Abraham and Sarah moved from the Southeast Ward to the Southwest Ward, buying a house and store at the corner of High and Laurel Streets. He bought the house and store from Conrad Zimmerman, who had been running a grocery in the store.

The house was a two-story frame house and the store was a one-story frame building attached to the house. The house and store were on a large corner lot that ran all the way to Lafayette Street, and contained four other adjacent frame houses facing Laurel, and two larger brick houses facing Laurel at the intersection with Lafayette. The lot also contained the house and store at 705 and an adjacent house at 707, both facing High. Abraham rented out the other houses while living in 705 High and running the grocery store there.

The store must have been successful, because, ten years later, in 1923, he replaced the frame house with attached store with a three-story brick house and store. He also built four other connected two-story brick houses along High south of the corner store. Ansel and his family lived in 707 and ran the now larger grocery store on the first floor of 705. They rented out the upper floors of 705 as apartments. The buildings he built a hundred years ago in 1923 are the same ones present today.

Abraham Ansel retired from the grocery business in 1936, and lived the rest of his long life of ninety-eight years on Chestnut Street. When he retired in 1936, his son Walter and his wife Sarah took over the store at 705 High. Walter then bought the house and store at 705 from his father in 1946, and continued operating the grocery there for another forty years. In 1985, Ansel sold the house and store to Kyoo Shik and Young Im Cho, who reopened the store as the Y&C Grocery, a business that lasted about twenty-five years. The next and present owner, Yoangel Plata-Cabrera, took over in 2016 and continues to operate the store as the V&Y Mini Market 2.

The storefront that Ansel built in 1923 is still largely present. The cornice can be seen extending past both sides of the large modern canopy and signage, and the large display windows with transoms, although mostly covered now, can still be seen on either side of the canted doorway with its sidelights. The doorway sits five steps up from the sidewalk, and like many storefronts built after 1900, there are no bulkheads below the display windows.

SoWe Store Stories: 502 High St, Ernst Roehm’s grocery (1895)

This article is part of a series of posts from SoWe Volunteer Historian Jim Gerhart about the stories behind the stores on Old Cabbage Hill

Many people will remember 502 High as the Hi-Fi Café, and indeed that is what it was for some 20 years. But fewer people know that 502’s early days were spent as a grocery store, and like many stores on old Cabbage Hill, its builder and its early proprietors were German immigrants.

The building that stands today at 502 High was built over 125 years ago, but as old as it is, it was not the first 502 High on the site. The first 502 High also was a 2-story brick building, but its location on the northeastern edge of the lot proved problematic. The city had to remove the house in the fall of 1890 when the original 14-foot-wide Filbert Alley was widened to make East Filbert Street. After the widening, the lot that remained was only 14 feet, 7 inches wide along High.

In 1891, Ernst Roehm, who immigrated here in 1881, bought the then-empty lot from which the first 502 High had been removed. He also bought a 2-story brick building at 506 High, which is no longer there, and that’s where Roehm and his family moved, and where he opened a grocery store. After a few years, in 1895, Roehm built the house and store that became the second, and current, 502 High. He designed it as a long, necessarily narrow, house with a first-floor store, and he moved his family from 506 High into the upstairs of 502 High, and moved his grocery store into the first floor of his new building.

The store was built with its entrance canted at 45 degrees so that it faced the intersection rather than either of the two streets forming the intersection. Roehm eschewed the elaborate Victorian storefront features that had been popular for the previous several decades, settling instead on a more modest storefront with two display windows on either side of the entrance. Instead of heavy cornices over the two windows, he went with subtle arches in the brickwork.

Today, the old storefront looks different than it did originally. A small green roof has been placed over the door, the transom has been covered, the front door and display windows have been replaced, and concrete steps have been added.

Roehm did not stay long at 502 High, but it remained a grocery store under several different owners into the 1930s. The grocer who had the longest tenure in 502 High was Leo Huegel, who ran a grocery there for about 25 years. After Huegel’s grocery closed in the late 1930s, George and Marie Ziegler opened Ziegler’s Café in the first floor.

When the property changed hands in 1960, the Zieglers retired and the building’s new owner, Carl Bermel, opened the Hi-Fi Café there with his brother August. The Hi-Fi became a popular fixture on the Hill for the next 20 years. From 1967 to 1973, it was run by Erma Jaggers and was known as Erma’s Hi-Fi Café. When the Bermel family sold it in 1973, the new owner, Harry Martin, hired Charles Null to run the Hi-Fi, which he did until it closed in 1980. After it closed, the building and its first-floor store/café became a residence, which it has been over the past 40 years, under 8 different owners.

Jim Gerhart, April 2023

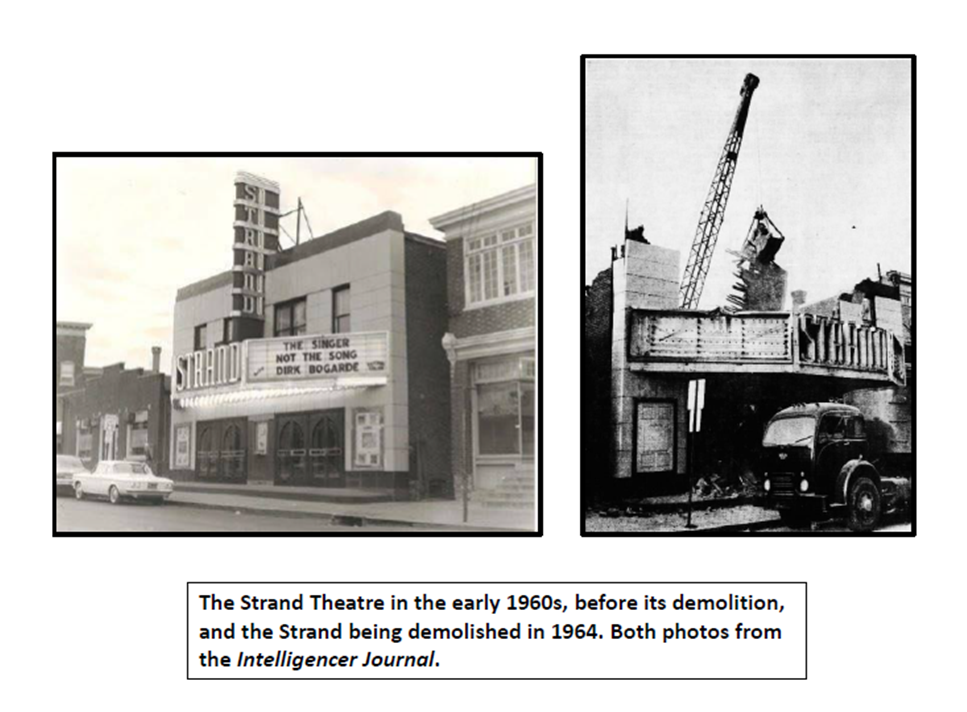

The Rise and Fall of Cabbage Hill’s Movie Theater

Jim Gerhart, March 2020

Movies, or moving pictures as they were first known, were invented in the 1890s. Within ten years, theaters devoted to showing movies began to proliferate. The first four large movie theaters in Lancaster were built between 1911 and 1914. They were the Colonial, Hippodrome, and Grand on North Queen Street, and the Kuhn on Manor Street. The three downtown theaters were more opulent and charged higher prices than the Kuhn, which was established to serve the working-class southwest Lancaster neighborhood.

The Kuhn Theatre, also sometimes known as Kuhn’s Theatre, opened in March 1911. Adam Kuhn was a German immigrant who attended St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, and who for many years, ran a successful bakery on East Chestnut Street. After much of his bakery was destroyed in a fire, he decided to retire from the baking business and venture into the new movie-theater business. He sold the damaged bakery in September 1910 and a month later he used the proceeds to buy a large lot in the 600 block of Manor Street for $1,950 (the lot was actually purchased in the name of Mary, his wife). On that lot, Kuhn built the Kuhn Theatre, which would eventually become the Strand Theatre and continue showing movies until 1962.

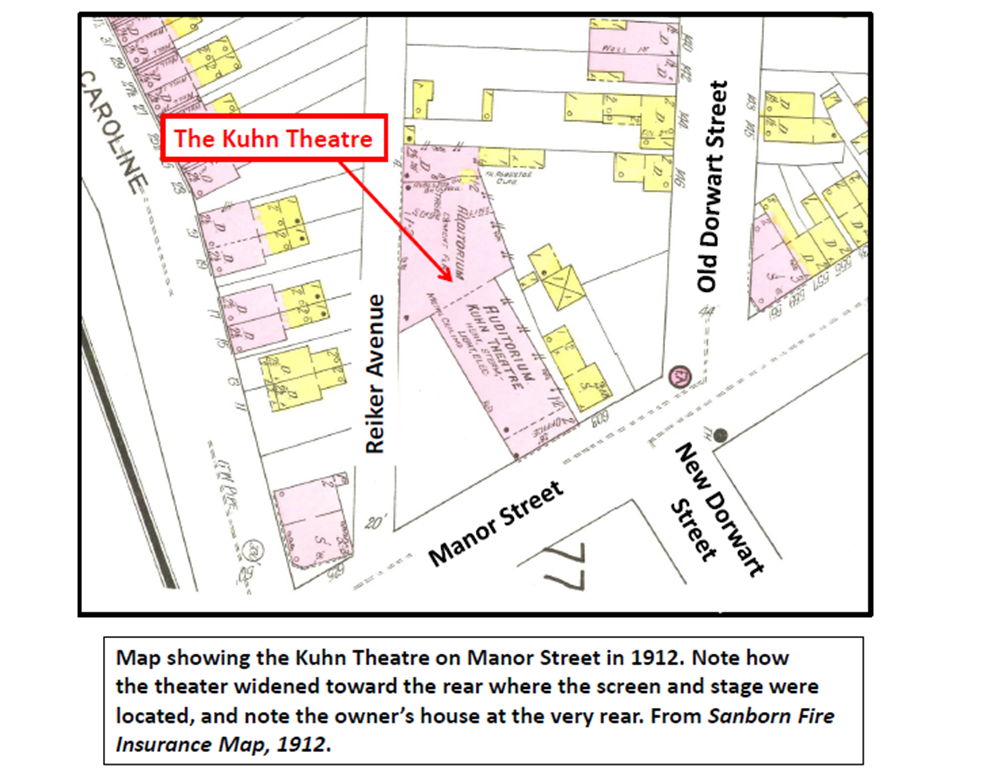

The Kuhn was located at 605-609 Manor on a large lot that extended to Reiker Avenue, and it stood nearly alone on that part of the block when it was first built. The brick theater had 40 feet of frontage on Manor, widening to 70 feet where the screen and stage were at the rear of the building. The building was 205 feet long, with a two-and-a-half-story brick house attached to the rear of the theater, in which the Kuhn family lived. The original theater, which could seat 400 people, was heated by steam and had both gas and electric lights. (The former site of the now demolished theater is a parking lot next to B&M Sunshine Laundry.)

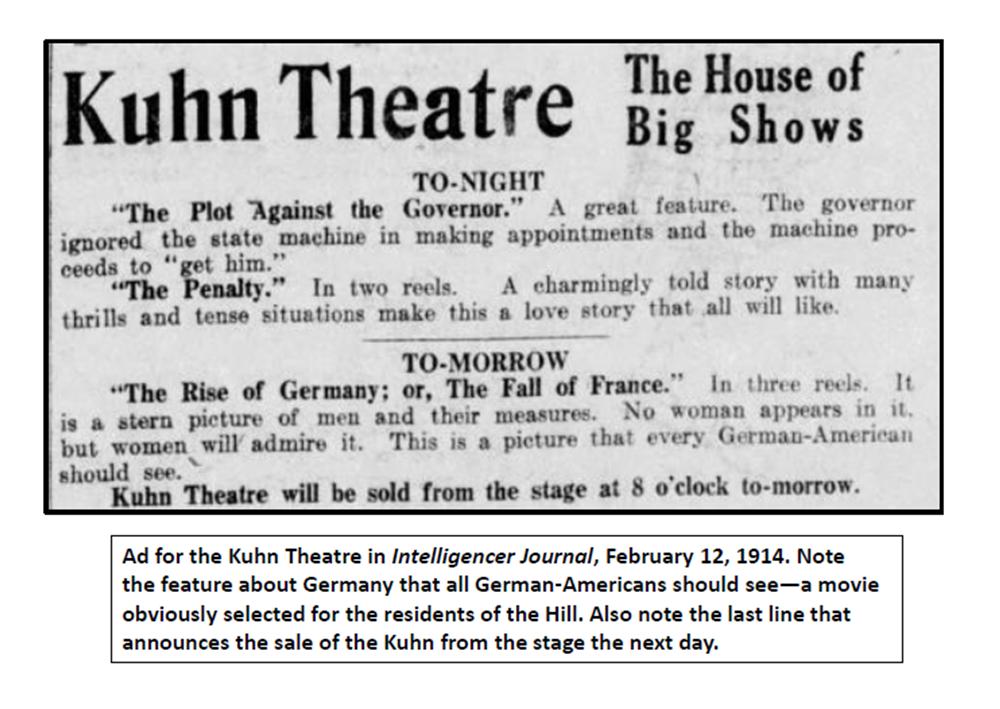

Adam Kuhn’s new career in the movie-theater business did not last very long. He died in the fall of 1912. Edward J. Kuhn, Adam’s son, took over ownership of the theater. Like most movie theaters in the early days, it not only offered movies, but also offered other types of entertainment such as vaudeville acts and band music. Kuhn also rented out the theater for use by others; one example was the Salvation Army for evangelistic services in 1914.

The movies shown at the Kuhn were quite primitive, black-and-white, silent movies that featured exaggerated acting and were usually about 15-45 minutes long. Each movie consisted of one to three reels of film; if there was more than one reel, the projectionist had to rewind and change the reels while the audience waited. The movies were accompanied by live piano music. Kuhn charged a nickel for most movies, and a dime for special events.

Edward Kuhn operated the theater through 1913, but in early 1914, he put the theater up for sale at auction. The advertisement for the public sale, held in the theater in February 1914, noted that the theater had been “a good money maker”. The highest bid was $15,000, but that was less than Kuhn thought it was worth, so the theater was withdrawn from sale. Kuhn tried again two weeks later, but again the theater was withdrawn from sale. Six months later, in August 1914, the theater was seized and sold to cover Kuhn’s debts. The Northern Trust Company bought the theater for $7,300. A couple months later, in October 1914, the Northern Trust Company sold it to two theater operators from Philadelphia for $8,300.

The two new owners, Peter Oletzky and Michael Lessy, changed the name of the theater to the Lancaster Theatre, and continued to offer movies and other forms of entertainment while remodeling the theater and increasing the seating capacity to about 900. By January 1916, a new theater manager had been brought on from Philadelphia. While movies were still the theater’s mainstay, other large events were held to augment the theater’s income. One such event was an April 1916 show put on by the Eighth Ward Minstrels accompanied by the St. Joseph’s Church orchestra and choir that attracted more than 1,000 people.

A big change in the program of the Lancaster Theatre was the addition of boxing matches. A boxing ring was set up on the stage for these events, and well-known local and regional boxers would stage matches that attracted packed houses. One example was a bout between Cabbage Hill’s own Leo Houck and Dummy Ketchell of Baltimore.

The Lancaster Theatre got another new manager in October 1916, and he announced a new policy of “musical comedy playlets of the higher class and unexcelled photoplays”. The opening act under this new policy was Rowe and Kusel’s Big Girlie Musical Review, an act that may have indeed been a change for the family-oriented audiences of the Hill. Prices were 5, 10, or 15 cents, depending on the seats. On the downside, because of competition from other attractions in the summer months, the Lancaster Theatre closed down for the entire summer in 1917.

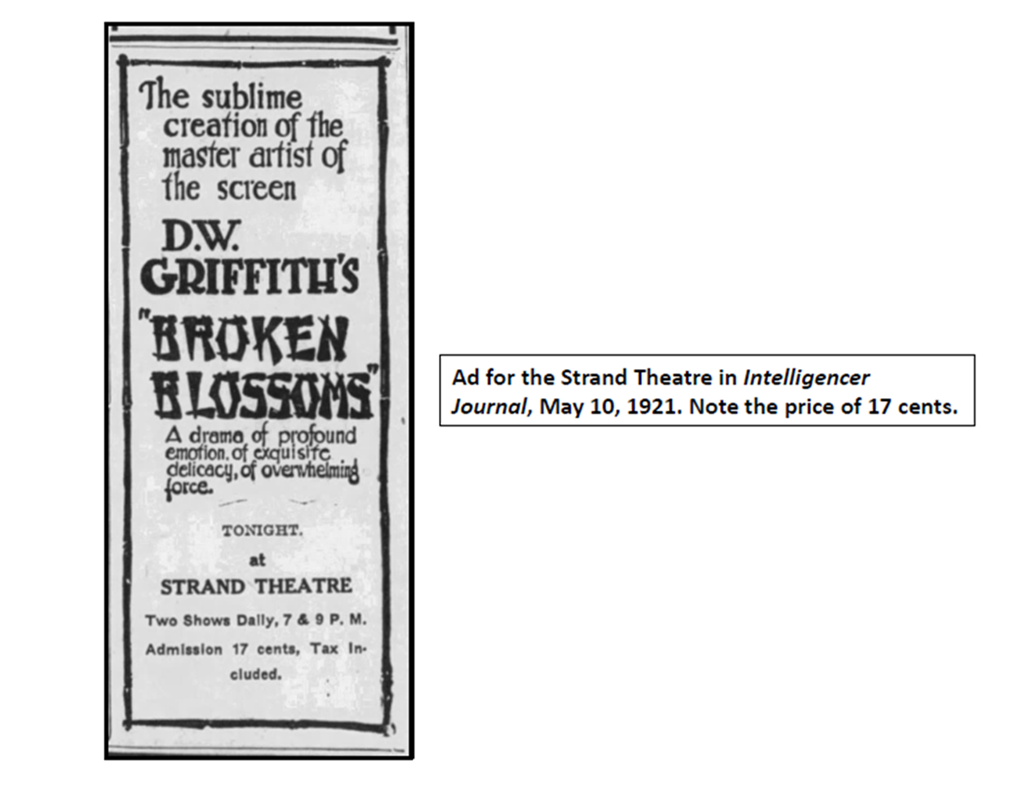

By the spring of 1919, the theater had changed hands again, and was doing business under the name of the Manor Theatre. Movies and boxing matches continued to be the two main draws. Movies had become much more sophisticated in the eight years since the theater had opened. They were still silent, but they had become longer, with more natural performances, and instead of anonymous actors, they now had recognizable stars who drew people to their movies. They also were now being made in Hollywood, California, instead of New York and New Jersey.

Other attractions drew crowds as well, such as a 7-foot eel caught by George Schaller, a neighborhood cigarmaker, in January 1920. Schaller put the eel in his backyard to freeze it solid, and then put it on display in the Manor Theatre. However, a monster eel was apparently not enough to meet the Manor’s profit expectations, and the theater was sold again in the spring of 1920, this time to George Bennethum of Philadelphia for $15,000. He remodeled the theater, updated its projection equipment, and changed the name of the theater to the Strand, a name it would keep until it closed 40 years later. Movies were still the staple, but boxing and other events also were staged. For instance, in the winter of 1921-22, the Duquesne Boxing Club leased the theater for its winter season of matches.

In 1928, the Strand Theatre was sold to Harry Chertkoff, a Latvian immigrant who would own it until he died in 1960. Chertkoff went on to own numerous other theaters in Lancaster County, including the King Theater and the Sky-Vue and Comet drive-ins. His first infrastructure improvement at the Strand was to outfit it for sound to accommodate the industry’s switch to movies with soundtracks. Chertkoff also made major renovations to the Strand in 1933 with the addition of improved acoustics and speakers, and again in 1939 with air conditioning and new seats. He also continued the practice of keeping prices as low as possible. In 1948, when Lancaster City instituted a 10% amusement tax, Chertkoff upped his prices to a still modest 37 cents for adults and 15 cents for children.

After Chertkoff’s death in 1960, his son-in-law Morton Brodsky took over his business interests. The Strand had been losing money for several years, probably related at least partly to the rising popularity of television. In 1962, the theater stopped showing movies, and Brodsky decided to sell the property. While searching for someone to buy the lot and building, Brodsky proceeded to sell the seats, projection equipment, and screen. When the theater building didn’t sell, he decided to just tear it down, and in November 1964, the Strand was demolished. Brodsky stated that he was exploring several options for the site, but in the short term it would be graded and used for parking, which turned out to be the long-term plan as well, as the site is still a parking lot today.

The Kuhn/Lancaster/Manor/Strand Theatre was Lancaster’s only neighborhood theater; all the others were downtown. It was the entertainment center of the Hill, providing movies and other amusements at reasonable prices to Hill residents for more than 50 years. Many a child had his or her early movie experience in the theater, including yours truly in the early 1960s. The 1964 demolition of the last incarnation of the theater, the Strand, not only left a physical gap in the 600 block of Manor, but also a gap in the social and cultural environment on the Hill.

Lancaster City’s Love Your Block Grant!

Applications are now open for Lancaster City’s Love Your Block, Park Adoption Mini-Grants, and the Neighborhood Leaders Academy!

Want to clean up your stretch of road? Have a project idea on how to fix a local issue? Love Your Block provides funds of $500-$2000 for community-led projects addressing issues surround litter, urban blight, and façade improvements. The projects must affect the whole block and require a coalition of at least 5 neighbors from 3 different households. Americorps VISTAS, Renee and Christian, will assist with project management, scheduling, budgeting and implementation, so don’t worry about needing experience. Find more information about Love Your Block, along with an online application here.

Additionally, Lancaster has a Park Adoption grant that also provides $500-$2000 for projects improving and expanding the usability of local parks or green spaces. Find more information about Park Adoption, along with an online application here.

Applications for both grants are due by March 20, 2020. They can be submitted online or, physical versions can be mailed to City Hall at 120 N. Duke Street, Lancaster, PA.

The Neighborhood Leaders Academy is open for applications as well! The program is a six-month training and grant program for community leaders to imagine, develop, test and realize projects that build community and provide positive outcomes. The program will empower leaders in all Lancaster neighborhoods to encourage one another, identify problems, plan projects to beautify the neighborhood and remedy issues, and celebrate the community and each other. Applications are due March 27th, 2020. For more information click here.

If you have any questions or need any assistance, please reach out to Christian at ccassidy-amstutz@cityoflancasterpa.com or 717-869-2140 or Renee at raddleman@cityoflancasterpa.com or 717-869-2144.