Jim Gerhart, February 2020

Before Farnum (now Culliton), Rodney, Brandon, and Crystal Parks in southwest Lancaster City, and before larger regional parks such as Rocky Springs, People’s, and Maple Grove, there was a large park known as Schoenberger’s Park on the eastern edge of Cabbage Hill. It was a popular place for various family and social gatherings in the 1870s and 1880s. Unfortunately, it also was home to a gang that plagued the park and all of southern Lancaster for many years.

William August Schoenberger was three years old in 1851 when he immigrated to Lancaster from Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany, with his parents, August and Catharine Schoenberger. His father was a wealthy brewer, and William learned the brewing trade working in his father’s saloon on the east side of North Queen Street above Orange.

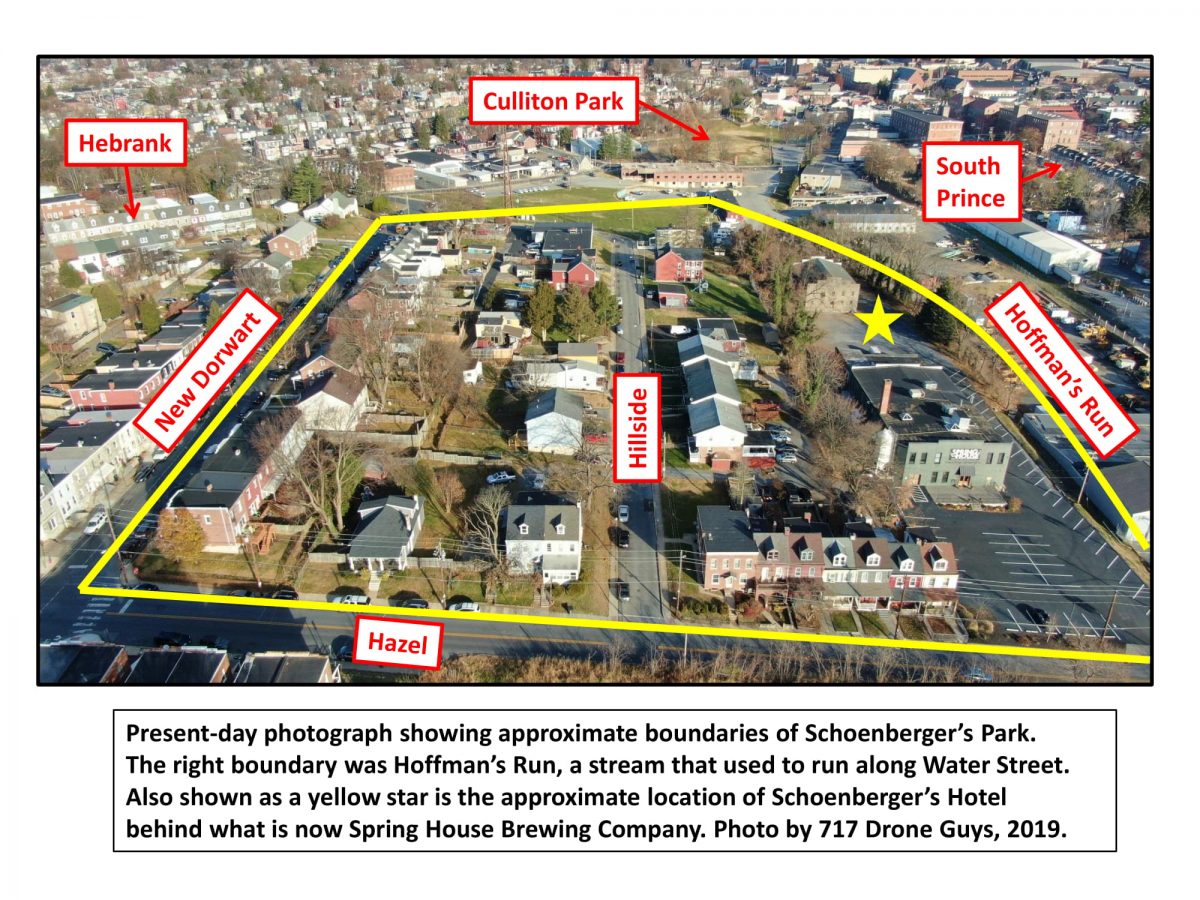

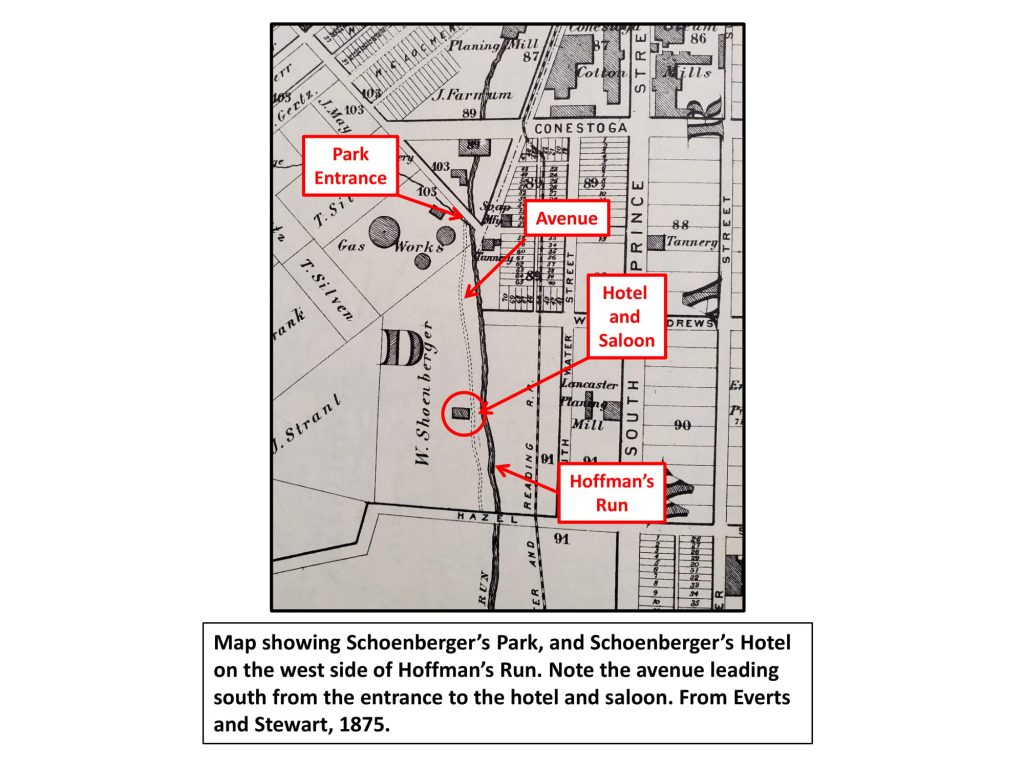

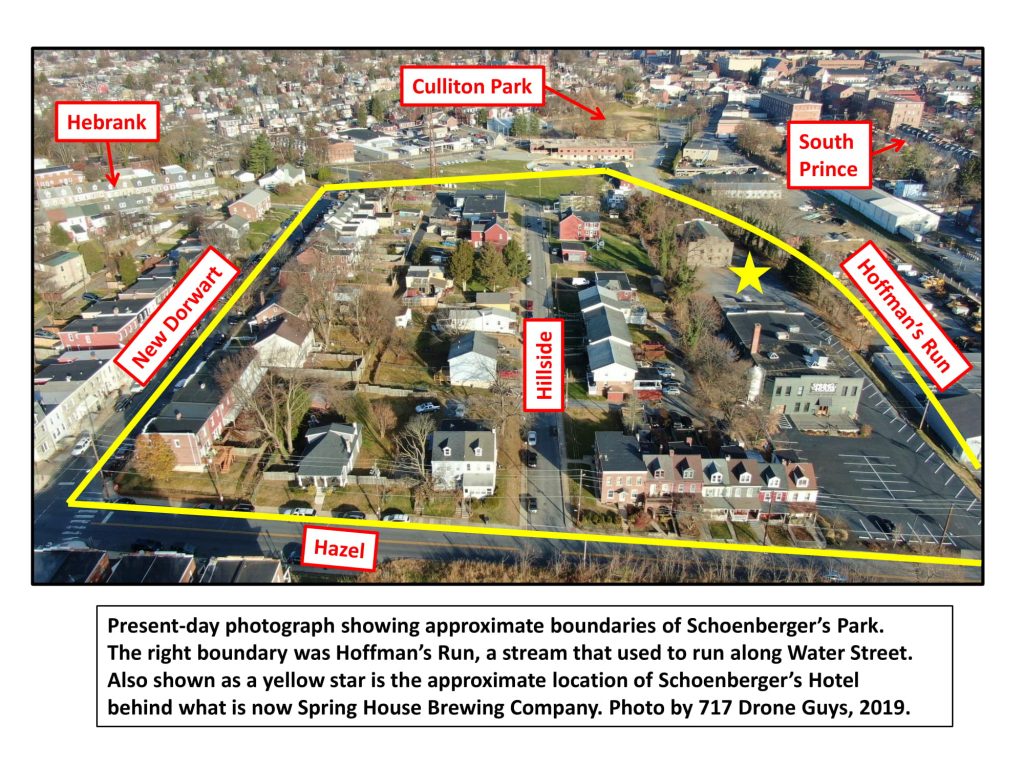

In 1869, when William was 21, he purchased a little more than nine acres of rugged land on the eastern slope of Cabbage Hill just west of Hoffman’s Run. Hoffman’s Run was a stream that ran north-south along Water Street until its last surviving reach was buried in a sewer in the late 1800s. The nine acres that Schoenberger bought was a mixture of meadows and woods, and was bounded on the west by what is now the southern leg of New Dorwart Street, on the north by the old gas works, on the east by Hoffman’s Run, and on the south by Hazel Street.

By the early 1870s, Schoenberger had built a two-story brick hotel with six rooms and a saloon, which became known as Schoenberger’s Hotel. The hotel was on a level spot on a slight rise on the west bank of Hoffman’s Run, behind what is now the Spring House Brewing Company. A boarded-up, cinder-block warehouse stands near the site now. Schoenberger built a large beer vault that was used to store his beer, as well as the beer of other Lancaster breweries, most notably Wacker Brewery. The beer vault was 68 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 14 feet high, with an arched ceiling. Schoenberger left the rest of the land in meadows and woods, creating a park-like setting that would attract the residents of Lancaster.

The entrance to Schoenberger’s Park was a bridge over Hoffman’s Run about 200 feet south of Conestoga Street, due south of what is now Conlin Field in Culliton Park. An avenue shaded by planted trees wound its way through a meadow along the west bank of Hoffman’s Run and then up a slight rise to the hotel. The hotel, which had gardens of flowers planted around it, was on the edge of the more rugged, steep, forested part of the park to the west. A wooden dance floor encircled a large tree near the hotel. An old-timer, Charles A. Kirchner, recalled in 1938 that “people went for walks and picnics in the park”, and that it was “a beautiful place with grass and trees—some fruit trees…”

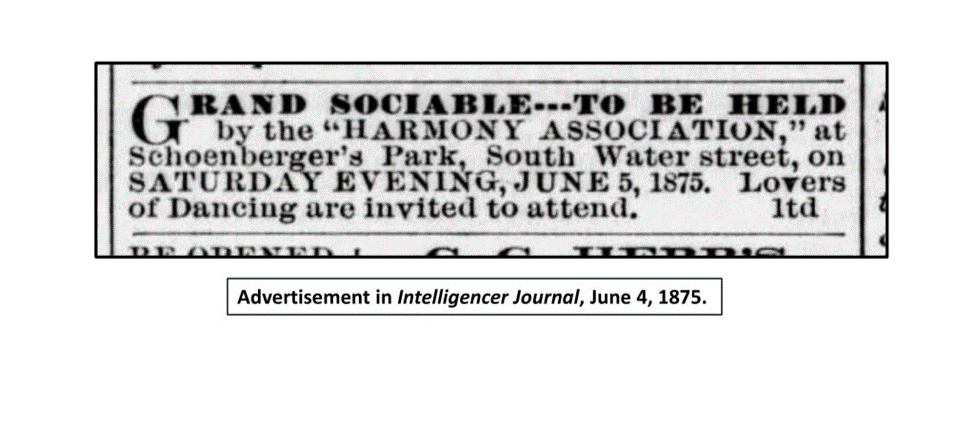

In addition to a place for people to take walks and enjoy picnics, the park quickly became a popular spot for larger gatherings. In the 1870s, various clubs and other organizations held events there. Many of the events were “sociables” that involved music and dancing, organized by groups such as the Eighth Ward Club, the Sun Steam Fire Engine and Hose Company No. 1 (William Schoenberger was a member), and the Keystone Drum Corps. Daniel Clemmens’ City Band, the Fiddlers Three, and Godfried Ripple’s String Band were some of the providers of dance music. Other events included political rallies (the Meadow Reform Club of the Fourth Ward), pigeon shoots with turkeys as prizes, and Temperance Mass Meetings. One well-attended event was an ox roast in honor of the visiting Allentown Cornet Band.

William Schoenberger was deep in debt by 1876, and his park, along with his hotel, had to be sold at auction to repay his debts. Benjamin Greider bought the property at a sheriff’s sale. Schoenberger moved back in with his widowed mother at his late father’s saloon on North Queen and helped run the saloon there for a few years. Eventually, he had a long career as a bank messenger for the Lancaster Trust Company, dying at the age of 73 in 1922. The park continued to be known as Schoenberger’s Park for another 15 years after Schoenberger last owned it, but the hotel became known as Snyder’s Saloon when Greider brought on Michael Snyder, and then Michael’s son Adam, to run it, which they did into the late 1880s.

The park and its hotel had a good run in the 1870s and 1880s, but the combination of wayward young men, a secluded wooded setting, and beer, often led to violence and criminal activities. As early as 1875, drunken fights broke out and people were injured, thieves broke into the beer vault and stole kegs, and passersby were harassed and assaulted. The saloonkeepers didn’t always help their cause, as both Schoenberger and the Snyders were charged with selling beer on Sundays, which was against the law.

Things got even worse with the rise of the Meadow Gang in the late 1870s. A group of several dozen young troublemakers took advantage of the relative remoteness of the park to make it their hangout. By the mid-1880s, incidents were happening with increasing frequency. The city police could spare little manpower to the “suburbs” of southern Lancaster, but they tried to respond when they could. Often when the police were summoned, by the time they got to Schoenberger’s Park, the Meadow Gang was long gone.

Some of the nefarious activities of the Meadow Gang included: Saloonkeeper Michael Snyder was injured when hit by a chair in a fight with the Meadow Gang. A large amount of lead was stolen by the Meadow Gang from a plumbing shop on South Queen. A young man was seriously injured in a fight between the Meadow Gang and some young men from the Schiffler Fire Company. The Meadow Gang threatened to kill a man who had leased part of the park for grazing his cattle. Five members of the Meadow Gang were arrested for breaking into a railroad car near Hazel. The Meadow Gang ran a plow through a nearby field of tobacco and potatoes, damaging the crops.

One particularly nasty incident caused an uproar among the people of the city, and probably had something to do with the decline of the park. In the summer of 1885, a young girl 16 or 17 years of age claimed to have escaped from the Meadow Gang after having been held by them for two months in the area of the park. She claimed that she had been poorly fed and assaulted numerous times. Subsequent investigation into her claims revealed some inconsistencies in her story, to the point that it was not clear exactly what had actually happened. However, the damage had been done, the public was outraged, and the reputation of Schoenberger’s Park suffered.

The Meadow Gang was active in the park and the rest of southern Lancaster well into the early 1900s, with some of the same men staying active in the gang for more than 20 years. Even as late as the early 1920s, the Meadow Gang was still causing sporadic trouble. By the late 1920s, however, the gang disappeared from the scene. Strangely, as time passed, memories of the Meadow Gang seemed to soften, with their less severe antics remembered somewhat fondly and their more serious crimes downplayed.

In 1931, one Lancaster newspaper even did a feature story on the old Meadow Gang, with a headline, “Meadow Gang 1880s Flaming Youth”, comparing them to the harmlessly rowdy youth of the Roaring Twenties. In the article, an original member of the Meadow Gang was interviewed and claimed that the more serious crimes attributed to the gang had not actually been committed by its members. According to him, they were just young men acting out, with no serious offenses to their name. True or not, the Meadow Gang was instrumental in changing the park from a nice place to visit to a dangerous adventure.

The park was purchased by Stephen Owens in 1889, and a small limestone quarry was opened on its western edge, on the lower slope near the hotel/saloon. Owens then sold part of the park to the Lancaster Gas Light and Fuel Company in 1895 to expand the gas plant. By the mid-1890s, the hotel was gone, and much of the land was subdivided for building lots. Streets were laid out and houses began to be built on the slope above where the hotel had been. The 25-year run of Schoenberger’s Park was over. By then, new city parks had been established, and memories of Schoenberger’s Park began to fade.

Today, the site where bands once played and people once danced, and where the Meadow Gang once roamed, has become the home of Spring House Brewing Company and the first blocks of New Dorwart and Hillside off Hazel. It’s hard to visualize now, but there used to be a “beautiful place with grass and trees” called Schoenberger’s Park in southwest Lancaster more than 125 years ago.