Jim Gerhart, March 2021

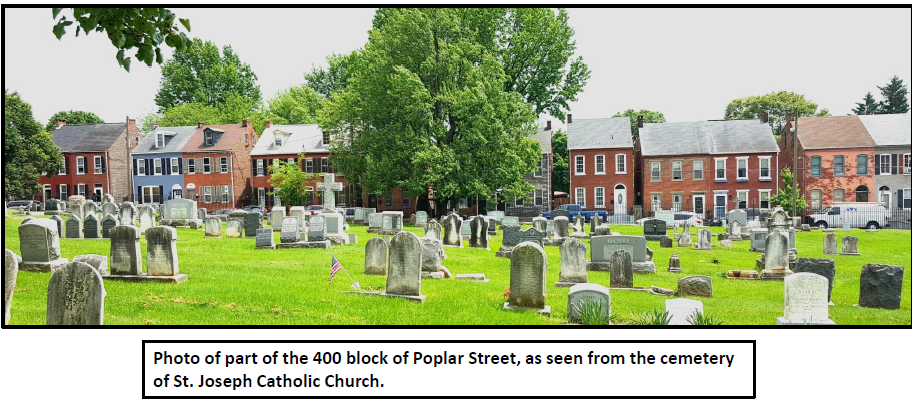

They were once the dominant style of house on Cabbage Hill, but now they are far outnumbered by Victorian rowhouses and duplexes. Most have been torn down, and many of the ones that remain have been remodeled and disguised to the point that it’s hard to recognize them anymore. Nevertheless, if you pay attention, you can still see good examples of the original house style of old Cabbage Hill—the small one-story house (also sometimes known as the one-and-a-half-story house).

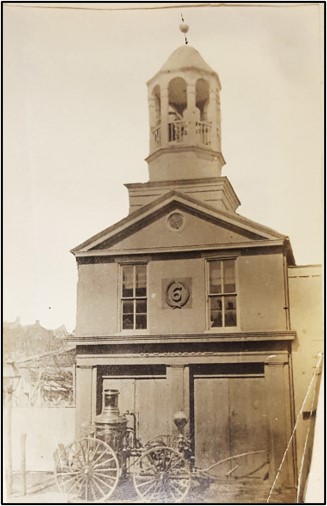

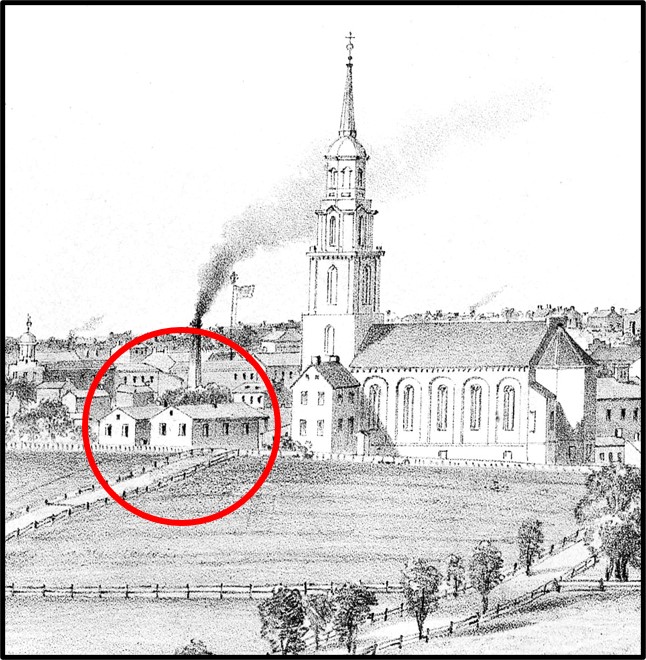

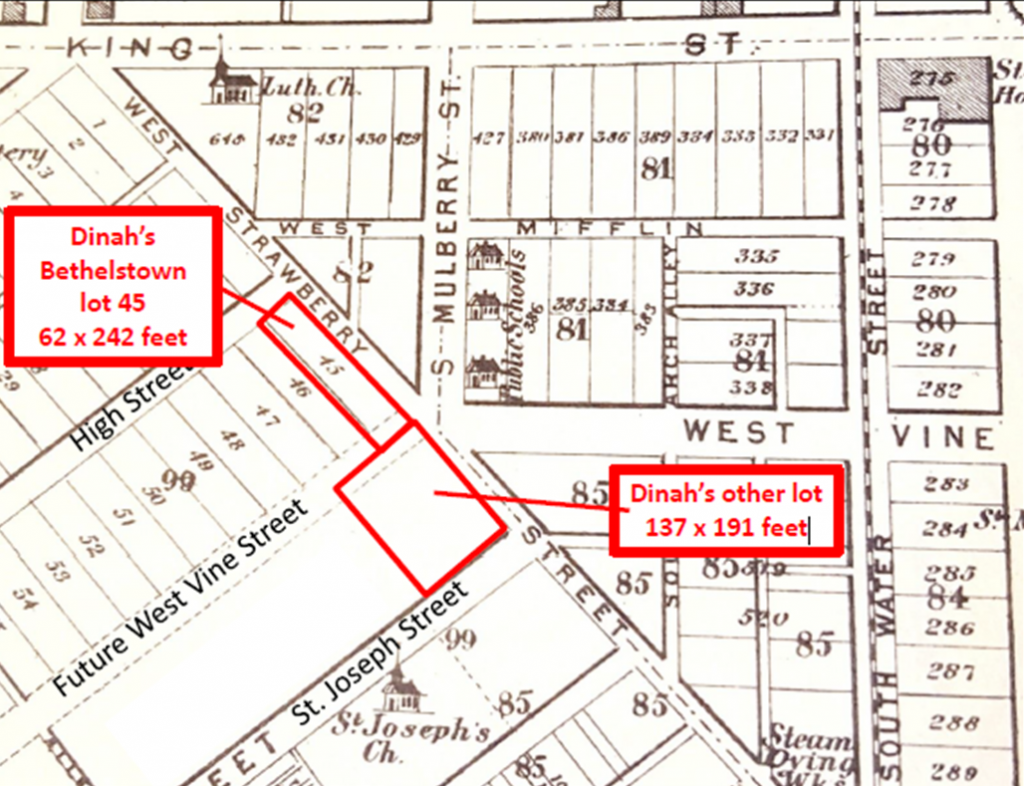

Before 1750, what would eventually become known as Cabbage Hill had only a few scattered houses and farm buildings, constructed mostly of hand-hewn logs. By 1800, a cluster of houses had been built in Bethelstown—the first two blocks of Manor and High Streets—while the rest of the Hill was still undeveloped. In Bethelstown, in 1800, the number of houses was only about 20, with some made of brick but still mostly of log, and nearly all one-story.

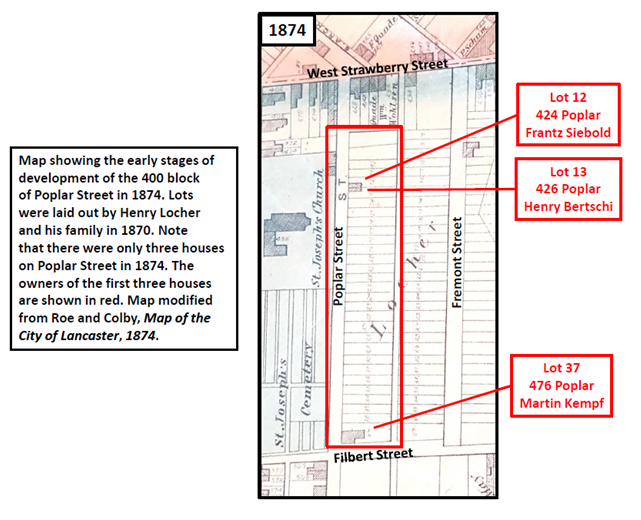

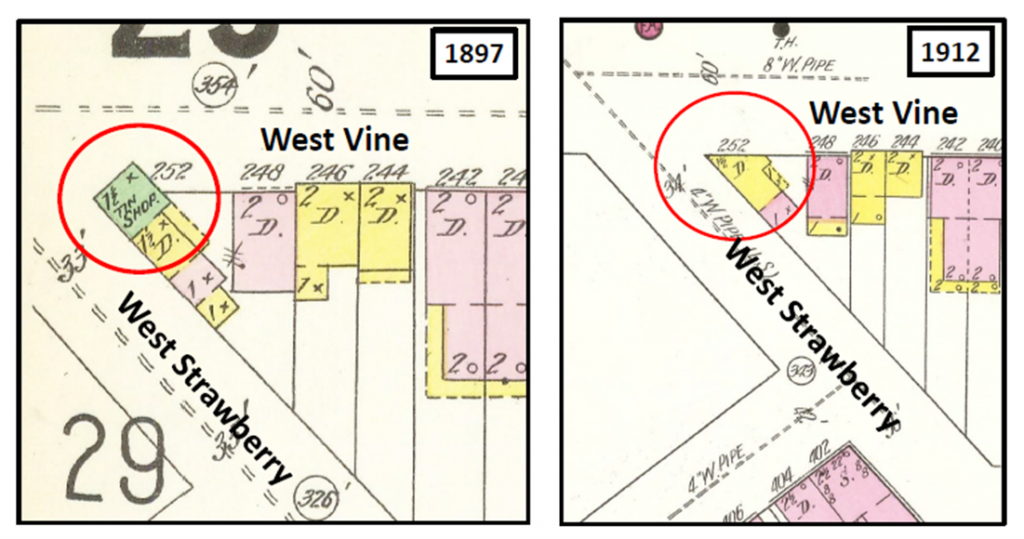

By 1850, Bethelstown had grown to nearly 100 houses, with a few two-story houses appearing but still with mostly one-story houses. Brick was fast becoming the most popular construction material. Shortly after 1850, the rest of the Hill began to be developed, with a mixture of two-story and one-story houses being built, mostly with bricks. By 1875, brick houses were being built by the hundreds all over the Hill, and nearly all of them were larger and of two or three stories. The era of small one-story houses was mostly over, and as they began to age, many were torn down and replaced with the larger, multi-story houses that dominate the Hill today.

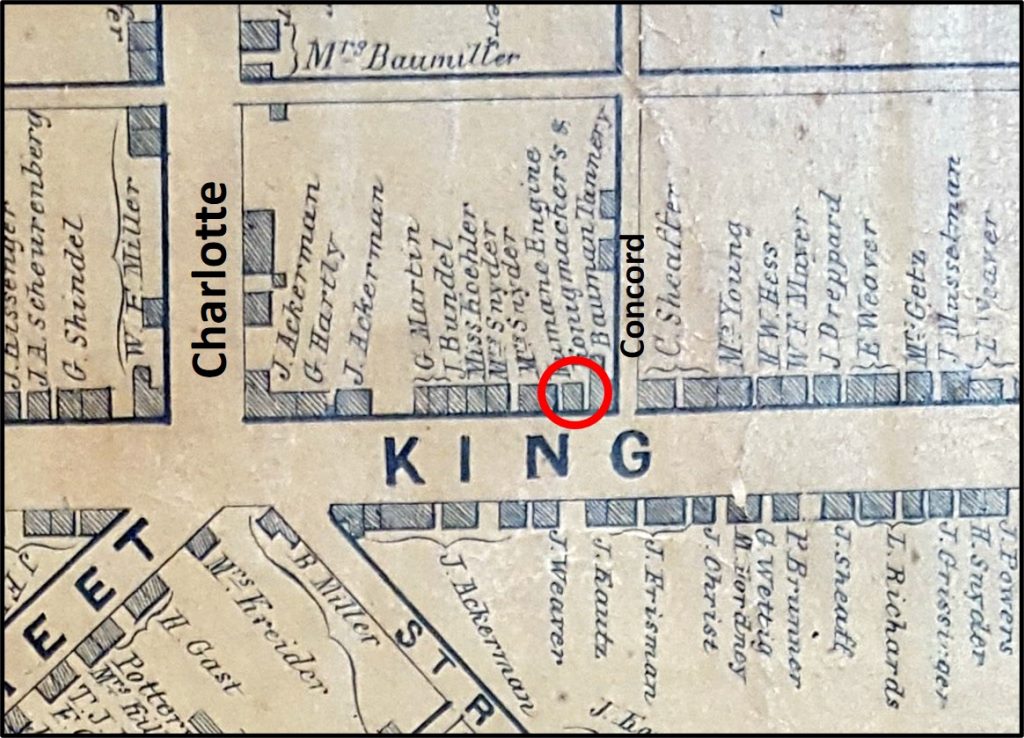

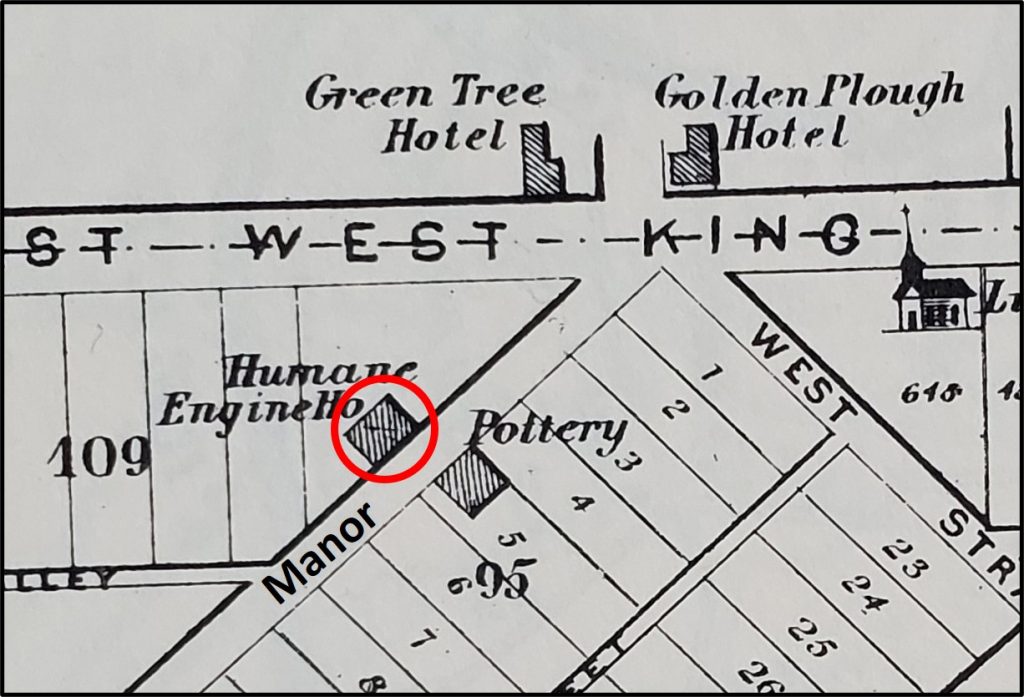

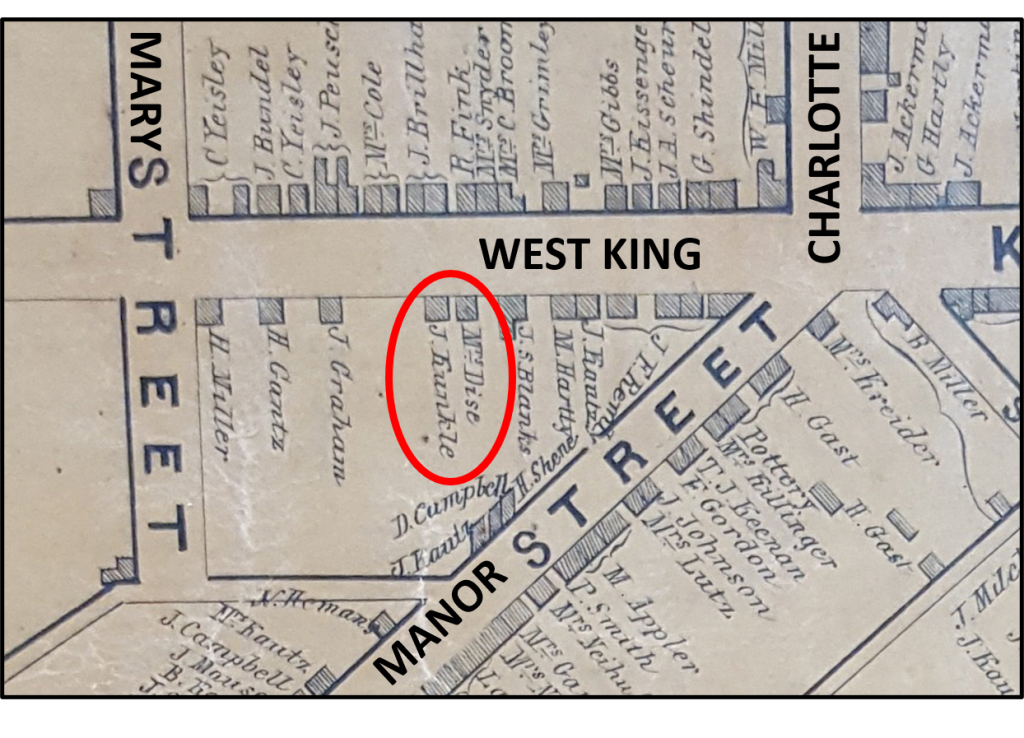

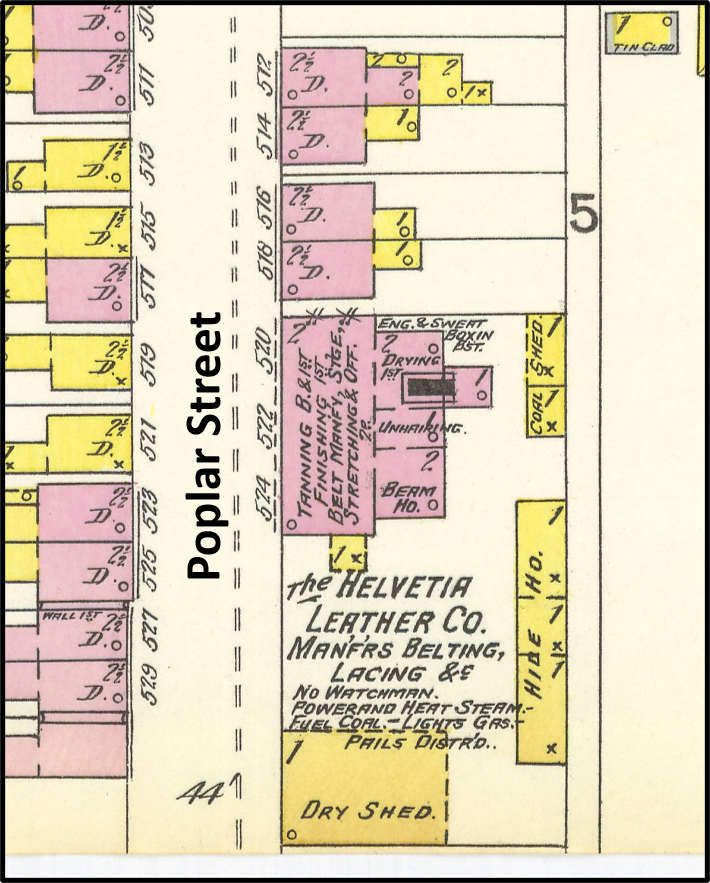

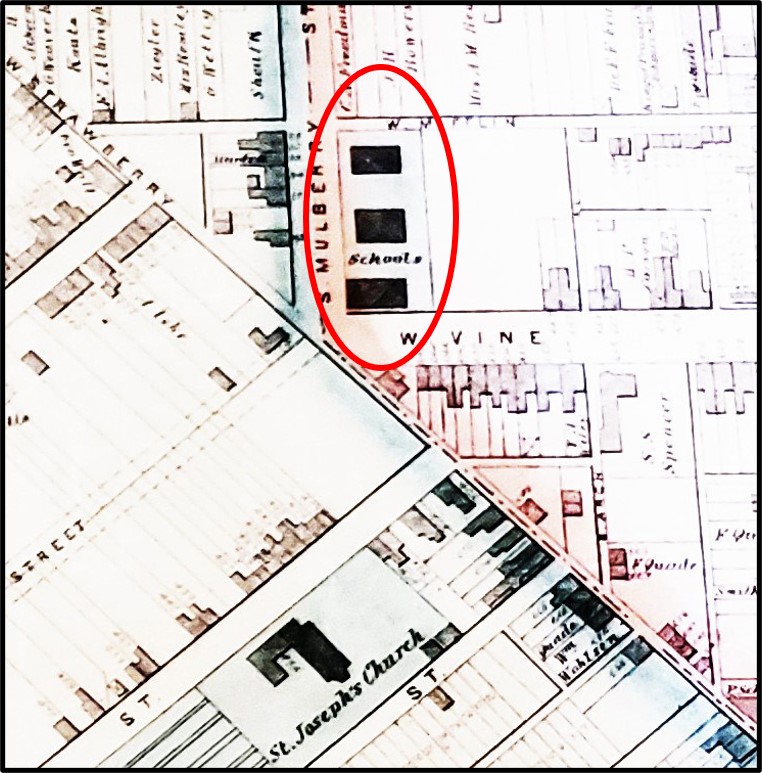

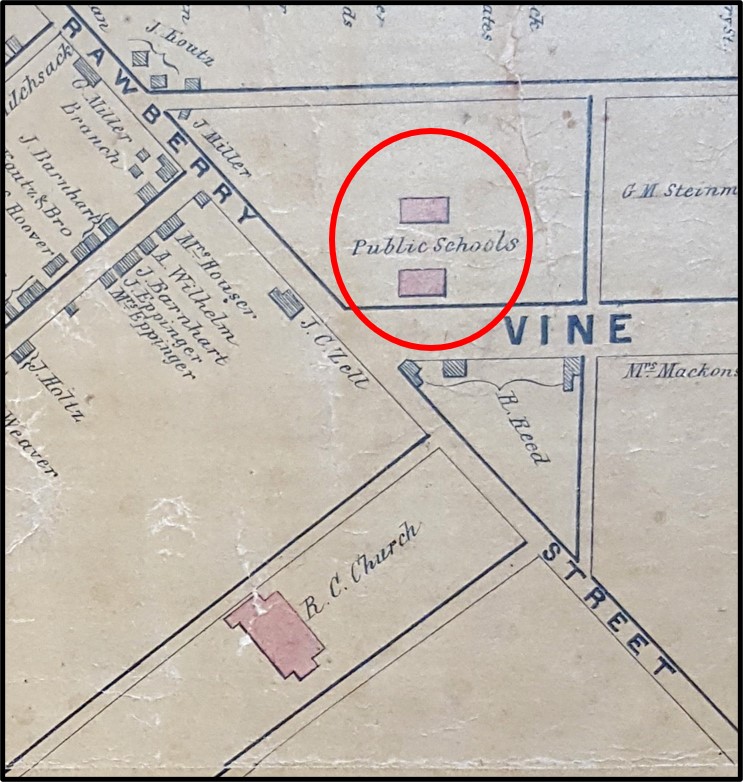

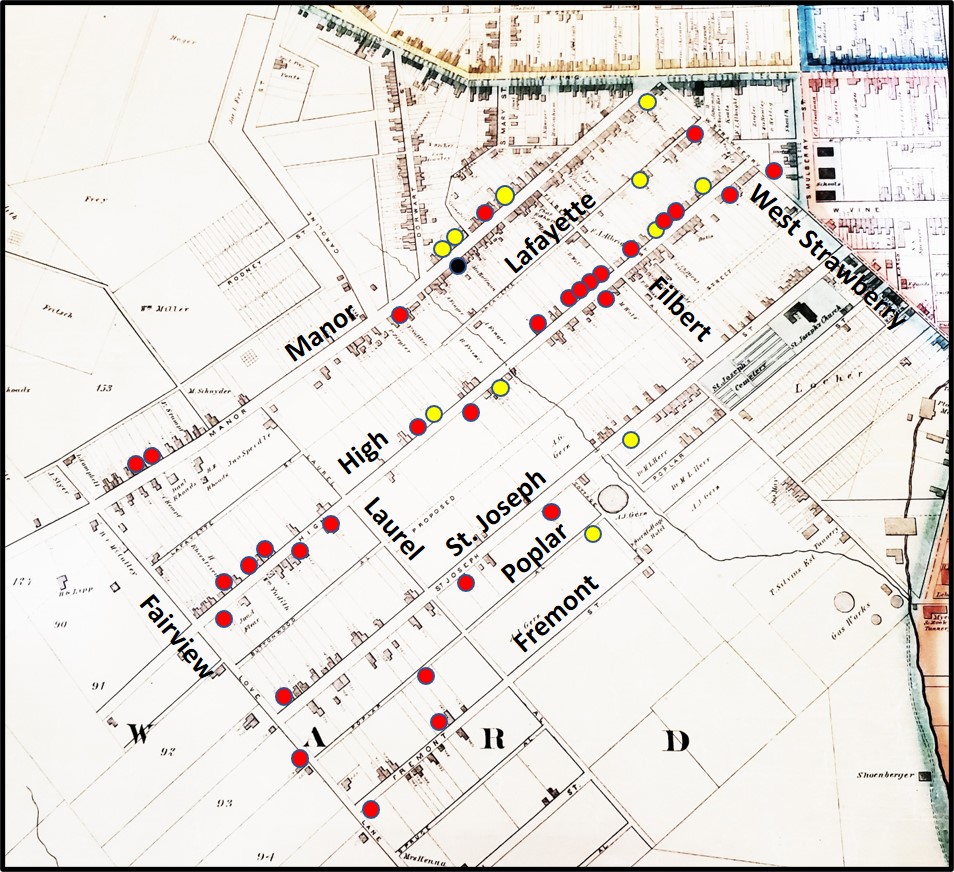

The 57 one-story houses on Cabbage Hill today, shown on an 1874 map. 31 single houses are denoted by red circles; 11 house pairs are denoted by yellow circles; and a grouping of four houses is denoted by a black circle.

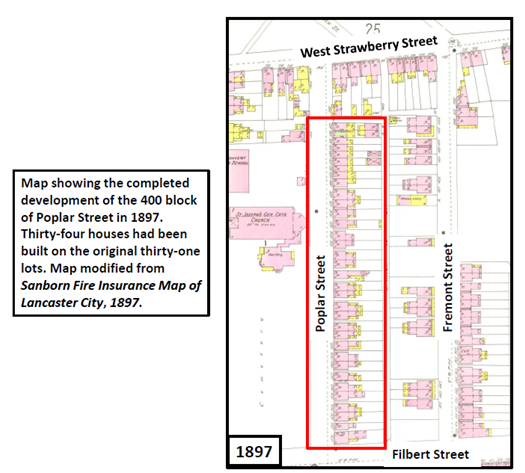

When the era of small one-story houses ended about 1875, there were about 150 of them on Cabbage Hill, as defined by the area bounded by Manor, West Strawberry, Fremont, and Fairview. By the early 1900s, that number had been reduced to about 120 as some were replaced with larger houses. Today, there are only 57 one-story houses left on the Hill. High Street and Manor Street, which include what used to be old Bethelstown, have the most, with 26 and 16, respectively. St. Joseph (5), Poplar (3), Lafayette (3), Fremont (2), Fairview (1), and West Strawberry (1) don’t have nearly as many. Of the one-story houses that remain, 36 are brick and 21 are wood frame.

Thirty-eight of the 57 remaining one-story houses were built before the Civil War, with 31 of them being built in the 1850s and the other seven in the 1840s or earlier. The great majority of the 38 houses built before the Civil War are in the first two blocks of Manor and High. Another 11 of the remaining one-story houses were built in the 1860s, and eight were built after 1870, including a few as late as the 1880s and 1890s. The great majority of the one-story houses built in the 1860s and later are not on Manor and High, but in surrounding blocks where development was spreading after the Civil War.

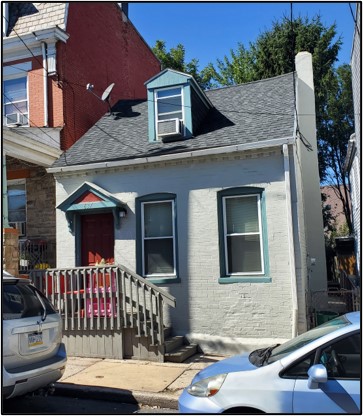

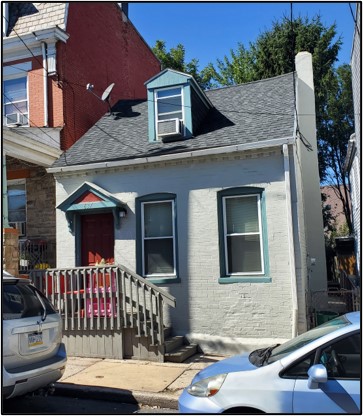

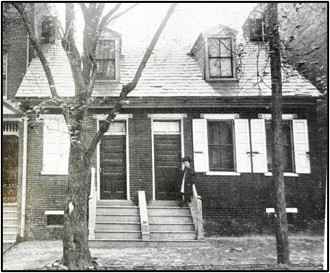

637 High Street was built by Frederick Heilman about 1859. Heilman was a weaver as well as a saloonkeeper on South Queen. After his death, when this brick house was advertised for sale in 1883, it was described as having a lot that was 54 feet wide and 226 feet deep, a one-story brick kitchen, a weaving shop, and fruit trees. Today, the house has a new door and windows, and is painted light green, but its basic appearance is pretty much the same as when it was new.

Although all the remaining 57 one-story houses are relatively small, they are not all the same size. The smaller houses have just two bays (a door and one window on the front), with the smallest two-bay houses measuring only about 11 feet wide (412, 545-547, and 549-551 Manor). The larger houses have four bays (a door and three windows on the front), with the largest of these approaching 20 feet wide (416, 539 High). All are at least as deep as they are wide, and some have additions attached to the rear of the house, some of which are original. Square footage ranges from less than 500 to more than 1,000 square feet. Most have two to four rooms on the first floor and one to two rooms in the attic. Even though many families were large, houses did not have to be big in the mid-1800s. Working-class families did not own much furniture or have many personal belongings, and for many, houses were mainly protection from the weather.

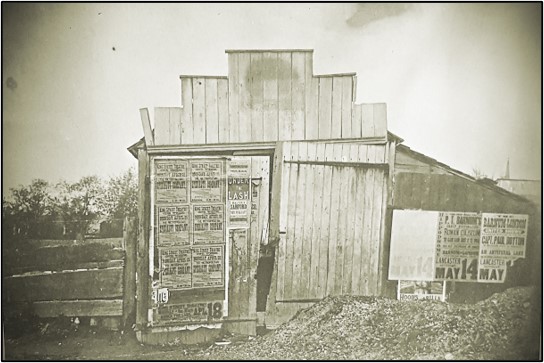

459 High Street was built by Xavier Frey about 1849, making it one of the 100 or so houses in Bethelstown in 1850. The original 62-foot wide lot extended to Lafayette Street, before the lot was subdivided both in width and length. The exterior of the wood-frame house has been altered from its original appearance, with a new door, new windows, and a new metal roof. However, it still has old wood siding and shutters.

An interesting feature of the one-story houses on the Hill is the fact that many of them were built as pairs. Twenty-two of the remaining 57 houses are combined in 11 pairs. In most of these pairs, the two houses are symmetrical pairs (mirror images), where the house on each side is the same size but reversed in terms of the location of the front door. In a couple of the pairs, one side is bigger than the other, which makes them asymmetrical. In addition to the 11 pairs, there is one grouping where four houses are grouped into a connected row (548-554 Manor). There are also several instances where one side of an original pair has been converted into a two-story house, in which case the two-story house has not been counted among the 57 remaining houses.

Most of the one-story houses have first floors that were raised above street and sidewalk level. Many are about two feet above street level, and some are three feet or more above. There may be several reasons for this: (1) To minimize excavation; (2) to allow the first floor at the rear of the house to be level with the higher backyard; and (3) to elevate the front door above the dirt roads that would frequently flood and get muddy when it rained.

Nearly all of the remaining 57 one-story houses have been altered over the years. Some have had dormers added and some have had their original dormers enlarged. Some of the brick houses have had their brick painted. Many of the houses, both brick and frame, have been sheathed in aluminum or vinyl siding, and a fair number have had form-stone installed on their front sides. Most have had their original doors and windows replaced, and some have had front porches added. Nearly all of them have had their original roofs—wood or slate shingles—replaced with composition shingles or metal. Despite the alterations to most of the houses, several have retained most of their original character and no doubt look much the same as they did a century or more ago.

The 57 remaining one-story houses on Cabbage Hill are the survivors of a much larger population of such houses on the Hill. Most of the survivors have seen more than ten owners and dozens of different tenants, and some have undergone numerous and sometimes major alterations, both externally and internally. But even with all the changes, it is still possible to look at these houses today and imagine how the Hill must have looked in its very early years, when only widely-spaced houses like these were present. These early one-story houses are valuable in a historic sense, and they deserve to be respected by their landlords and tenants. It is important to make sure these old houses continue to survive as picturesque reminders of old Cabbage Hill.

Note: Once research facilities open up again, I will nail down a few loose ends and post a complete list of all 57 one-story houses on the Hill, along with dates of construction, builders’ names, and primary early owners.