Jim Gerhart, August 2019

Dinah McIntire died 200 years ago in Lancaster, in May 1819, at the reported age of 113. She was well known around Lancaster in the early years of the nineteenth century as the fortuneteller who worked at the White Swan Tavern in the square. Her death warranted a rare obituary in the Lancaster Journal, something usually reserved only for prominent male citizens, as well as a note in Reverend Joseph Clarkson’s journal about her burial in the St. James Episcopal Church cemetery, despite the fact that he was in Philadelphia at the time.

Dinah was one of the few women of her time who owned property; she had a small house near the intersection of West Strawberry and West Vine Streets. The site of her house was said to be near the highest point in that part of Lancaster, at the angle between West Strawberry and West Vine, and her notoriety was such that the hill on which she lived became known as Dinah’s Hill (see photo). By all accounts, she lived a remarkable life—all the more remarkable because she was African American and a slave for most of her life, including here in Lancaster.

looking east down the hill on West Vine. Dinah McIntire lived in a small

frame house at this intersection, which is near the highest point in this part

of Cabbage Hill, which was called “Dinah’s Hill” throughout most of the 1800s.

According to several sources, Dinah McIntire was born into slavery in the town of Princess Anne, Somerset County, Maryland, about 1706. She spent the first half of her long life in Maryland, and raised four children there. She was already in her fifties when Matthias Slough, a prominent early citizen of Lancaster, bought her and brought her north to work at his White Swan Tavern.

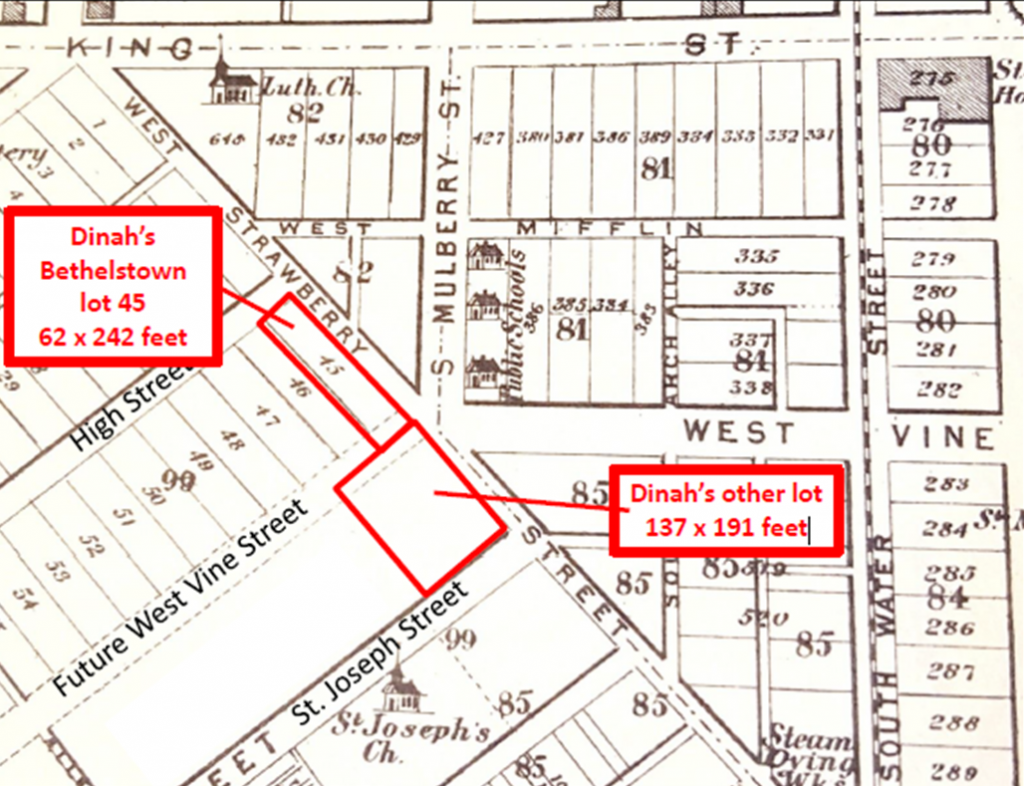

When Dinah died in 1819, she owned two, and possibly three, lots of land on the northeast edge of Cabbage Hill. She owned two of the lots as early as 1798, when the lots were taxed as part of the 1798 federal Direct Tax. The tax was based on the amount of land owned and the number of windows and the total number of panes in the windows. One of Dinah’s lots was 62 x 242 feet and contained an 18 x 22 foot house and a 15 x 20 foot stable. The house was a one-story log and brick house with two windows of six panes each, and the stable was made of logs. The other lot she owned in 1798 was larger and apparently not built on; it measured 137 x 191 feet, adjoining the first lot.

In 1816, three years before her death, Dinah McIntire, having long outlived her four children, prepared a will in which she left all of her property and belongings to Jacob Getz, a young Lancaster silversmith. Like Dinah, Getz attended St. James Church in 1815, when he and his wife Martha had their first child baptized there. By 1816, when Dinah wrote her will, Getz had apparently befriended her to such an extent that she named him as her executor and sole heir.

When Dinah died in 1819, Getz became the owner of Dinah’s property. Ground-rent records for Bethelstown, laid out by Samuel Bethel, Jr., in 1762, show that Jacob Getz became the owner of Bethelstown lot 45 after Dinah’s death. Lot 45 was 62 feet wide and 242 feet deep, and was bounded on its long dimension by West Strawberry between High and West Vine. This was clearly one of the two lots left to Getz by Dinah McIntire, and an examination of deeds shows that the other lot, which was a little larger, was immediately adjacent to the southeast across what is now the extension of West Vine southwest of West Strawberry (see map).

However, there is still some uncertainty surrounding exactly where Dinah McIntire actually lived. One obvious possibility is the 18 x 22 log and brick house on Bethelstown lot 45. But the most likely place for a house to have been built on that lot was on the High Street end of the lot. At the time Bethelstown was laid out, the other end of the lot did not front a street (the extension of West Vine Street didn’t occur until much later). And if Dinah had lived on the High Street end of lot 45, she would not have been at the angle of West Strawberry and West Vine, and she would not have had a direct view down the hill on West Vine, as numerous writers have claimed for her.

An article in The News Journal of Lancaster on June 9, 1898, provides an alternative, and I think more likely, location where Dinah may have lived. The article discusses how “another old landmark of the city” was about to be removed. The landmark had been condemned because it was too close to the street and had become an eyesore. That landmark was a small frame cabin on the corner of West Vine and West Strawberry, and the article states that it was reputed to have been the house where Dinah had lived almost a century before.

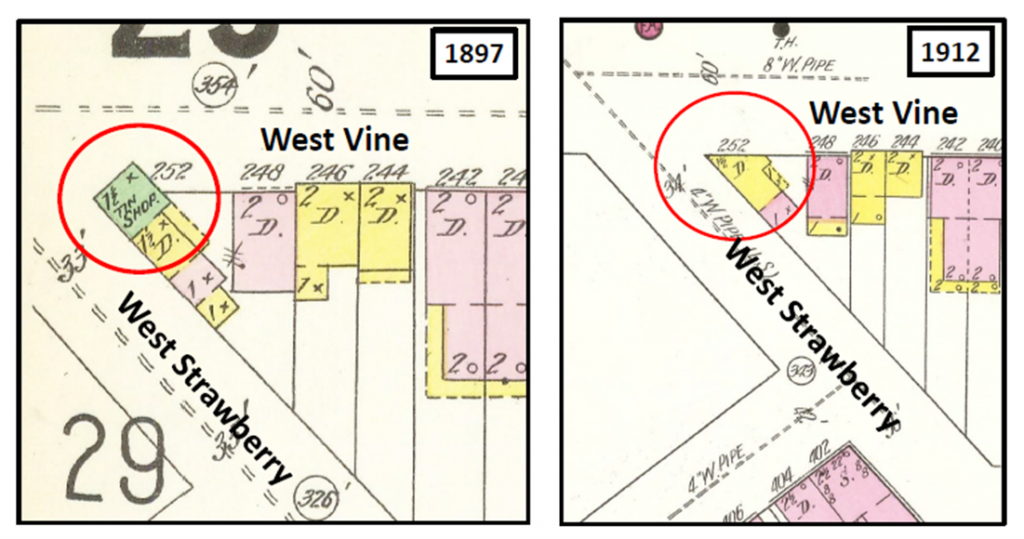

An examination of an old fire-insurance map of the city from 1897 shows that a small one-and-a-half-story frame house, then being used as a tin shop, did indeed stick out into the street at the angle where West Strawberry and West Vine meet. A 1912 fire-insurance map shows that the small frame house was no longer there, which is consistent with the claim of the newspaper article that the house was about to be removed in 1898 (see side-by-side maps). I believe it is likely that this small house is where Dinah McIntire lived, and that this small piece of land was the third lot that some writers have attributed to her. The exact site of Dinah’s little house was where the flagpole is today in front of the memorial to fallen soldiers.

jutting out into the street. An 1898 newspaper article stated that Dinah’s old house was about

to be removed. The 1912 map shows that Dinah’s old house was removed as planned. Maps

modified from Sanborn Insurance Maps of 1897 and 1912.

Now, to complete the story of Dinah McIntire, we are compelled to circle back to the potentially problematic life of Matthias Slough, Dinah’s Lancaster slave master. Slough was as prominent a citizen as there was in Lancaster in the late 1700s. During the Revolutionary War, he served as the Colonel of the Seventh Battalion of the Pennsylvania Militia, and saw action at the Battle of Long Island. He also served at various times as assistant burgess, county coroner, county treasurer, and member of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly and General Assembly, all while he was running the very popular White Swan Tavern.

Certainly, this is a fine list of accomplishments worthy of our respect. However, just like numerous other prominent Lancaster citizens in the eighteenth century, Slough’s legacy is compromised by the fact that he was a slave owner. From 1770 to 1800, Slough owned at least three to four slaves at a time. In fact, a registry of Lancaster slaves indicates he owned eleven slaves in 1780.

Curiously, Dinah McIntire is not one of the eleven listed slaves in 1780. Did Slough free her before 1780? We know she was freed at least by 1798, because she owned property then. It is possible she was freed before 1780, because it was common for slave owners to free slaves when they reached old age and Dinah was already in her seventies in 1780. Whether he freed Dinah before 1780 or closer to 1798, it is reasonable to think that the wealthy Slough may have rewarded her for her years of servitude, and that her ownership of land may have been a result of that reward.

Whether we should temper our respect for Matthias Slough because he was so thoroughly invested in the “peculiar institution” of slavery is a question for individual conscience and professional historians. It seems fitting, though, that Dinah McIntire outlived her former slave master Slough, and that her newspaper obituary was almost as long as his obituary. On top of that, Dinah was the only one of the two for whom a hill was named.