Jim Gerhart, September 2020

The 400 block of Poplar Street, one of the most picturesque blocks on Cabbage Hill, dates back to October 5, 1872. On that date, at 2:00 p.m., a public sale of building lots was held as part of the estate settlement of Henry C. Locher, the developer of the lots, who had died the previous year.

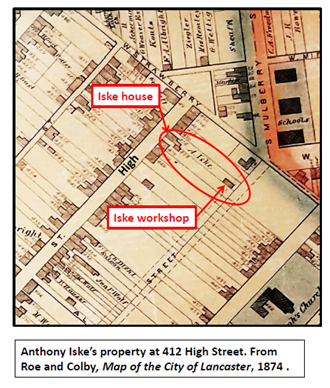

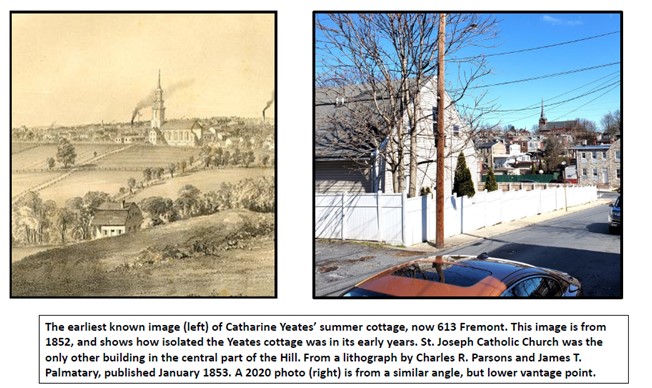

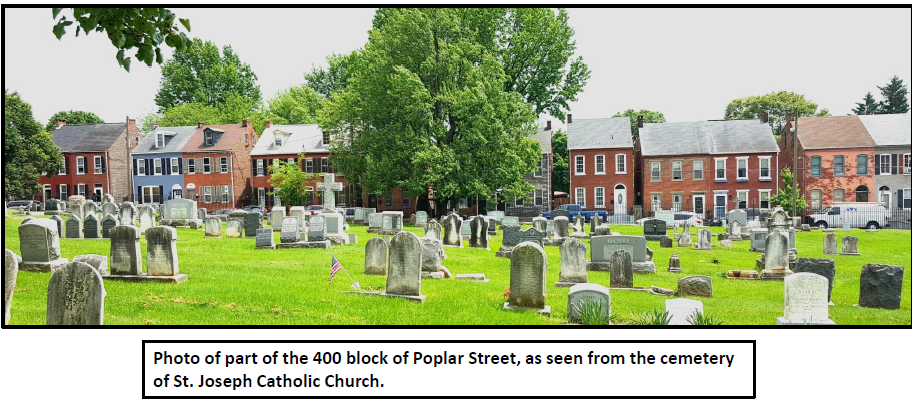

First, by way of a little background…..In 1872, the central part of Cabbage Hill was in the midst of a development boom, spreading from Manor Street eastward. In the west, the 400 and 500 blocks of Manor and High Streets in the Bethelstown neighborhood were almost completely built up, with the former Lafayette and Buttonwood (West Vine) Alleys beginning to be built on as well. Moving east, the 400 and 500 blocks of St. Joseph Street had acquired houses on about half of their lots. But on Poplar Street, although St. Joseph Catholic Church was on the northwest side, the southeast side of the 400 block was devoid of houses. With the October 1872 sale of Henry C. Locher’s lots, that was about to change.

Thirty-one lots on the southeast side of Poplar had been staked out by Locher and his family in early 1870. All but two of the lots were 20 feet wide by 100 feet deep; the exceptions were the two end lots that were a little wider at 30 and 27 feet. All the lots backed to an alley that would eventually become South Arch Street. The lots were numbered from 7 to 37. Bidders on the lots could bid on single lots or as many as three contiguous lots.

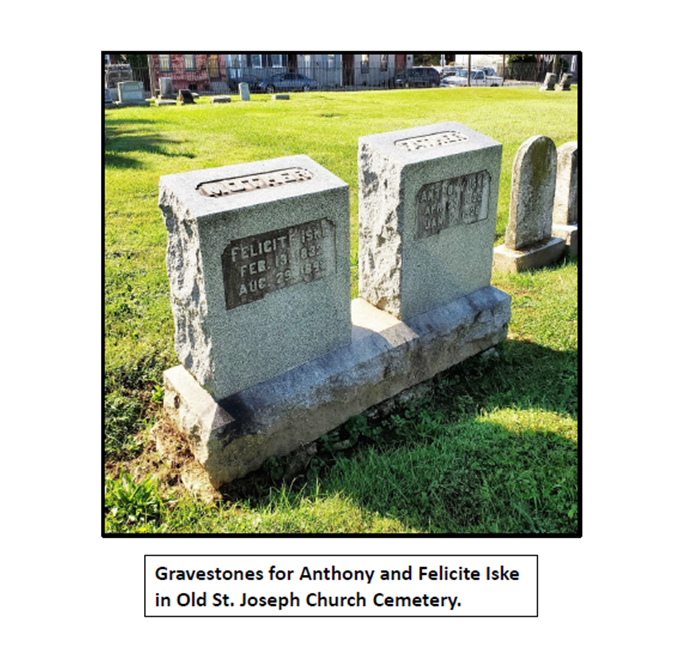

The sale took place across Poplar from the rear of St. Joseph Catholic Church and the adjoining cemetery, which had been established less than 25 years earlier. According to an announcement of the sale in the Lancaster Examiner and Herald: “These lots are pleasantly situated, on high ground, and in an improving and rapidly growing part of the city, and very desirable for building lots…”

The land had been purchased by Henry C. Locher and his wife Cecelia Margaretta from Daniel Harman just two years earlier in 1870. Locher laid out building lots shortly after buying the land, and first tried to sell the lots privately, without success. When Henry died in April 1871, Charles A. Locher was assigned to be the guardian of Henry’s and Cecelia’s youngest daughter, Laura, who was 10 years old and still a minor. The public sale of lots was arranged to generate enough funds to provide for Laura’s share of her father’s estate, to be managed by her guardian until she became of age.

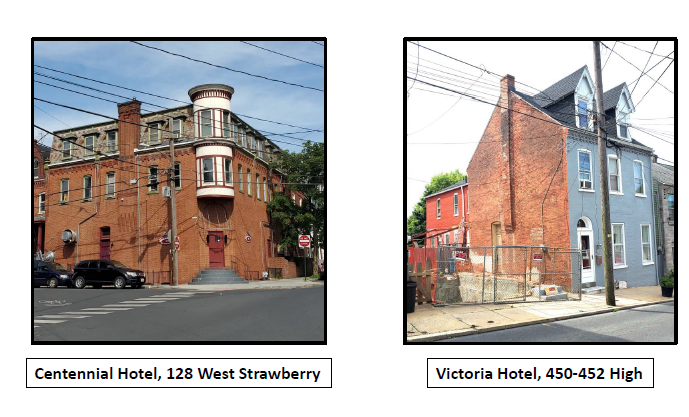

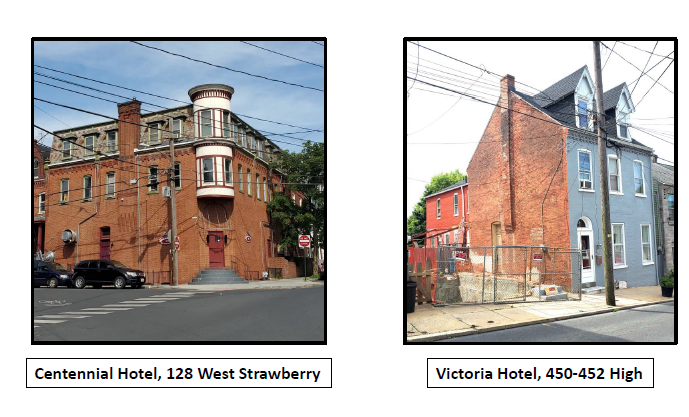

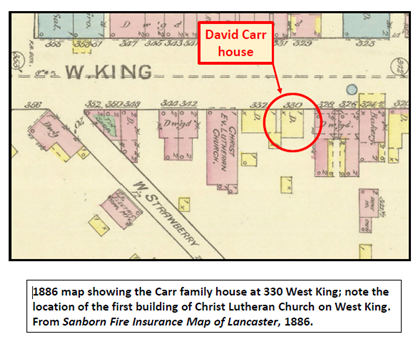

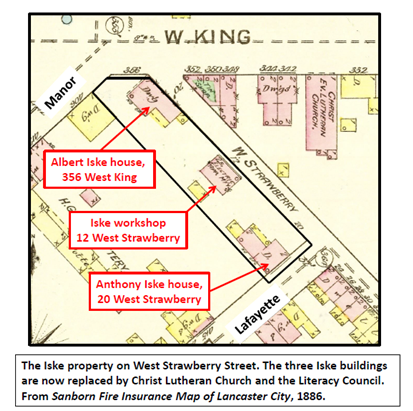

Henry C. Locher was able to invest in real estate because of his successful tannery located at the corner of West Strawberry and South Water Streets, where the wading pool in Culliton Park was until recently located. He and his wife Cecelia and their four daughters lived in a house next to the tannery. The tannery was established by Henry C.’s father and from the late 1830s to the early 1870s, it produced a specialized leather known as Moroccan leather that was made from goatskin.

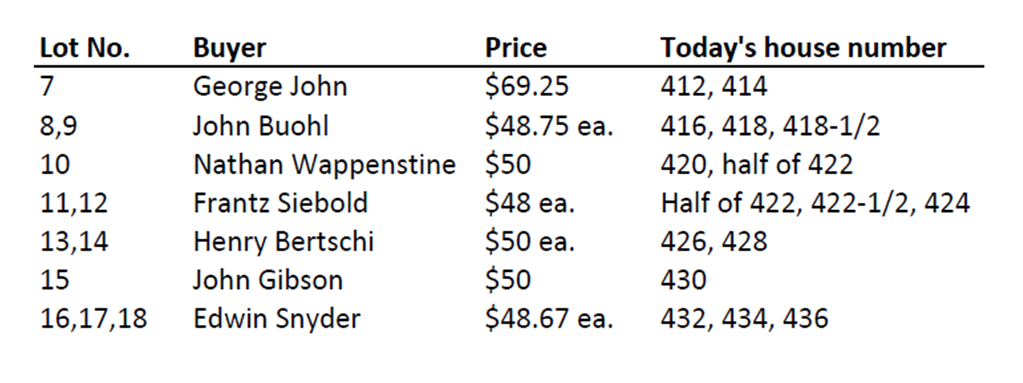

The public sale of Locher’s building lots on October 5, 1872 went well. A dozen lots on the southeast side of Poplar were sold that day, ranging in price from $48 apiece for lots 11 and 12, to $69.25 for lot 7 (the widest lot). The purchasers were required to pay half the price by April 1, 1873, and the other half, with interest, by April 1, 1874. The twelve lots that were sold that day in the 400 block of Poplar were:

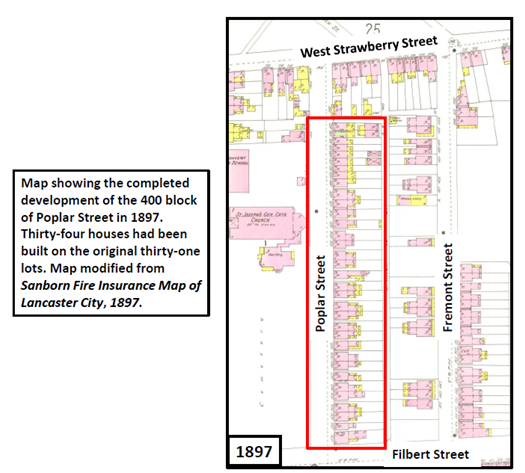

The building of houses on the recently purchased lots began shortly after the public sale. Most of the new lot owners kept their lots at the original 20-foot widths, but a few lot owners subdivided their lots before houses were built. Lot 7, with an original 30-foot width, was divided into two 15-foot wide lots. Also, two pairs of 20-foot wide lots, each pair having a total of 40 feet of width, were each divided into three lots a little over 13 feet wide. Lots 8 and 9, and lots 10 and 11, were combined and then subdivided in this way, so that four 20-foot wide lots became six 13-foot wide lots. The result was that thirty-four houses could be built on the original thirty-one lots.

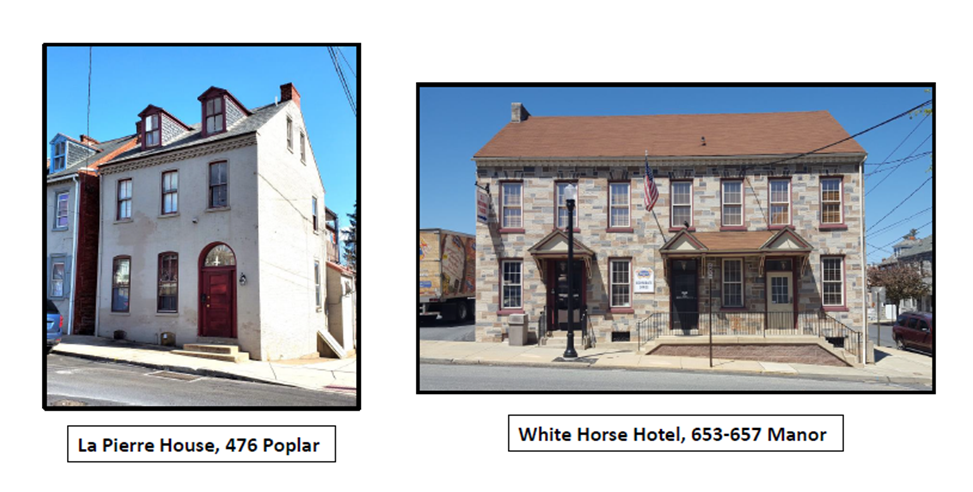

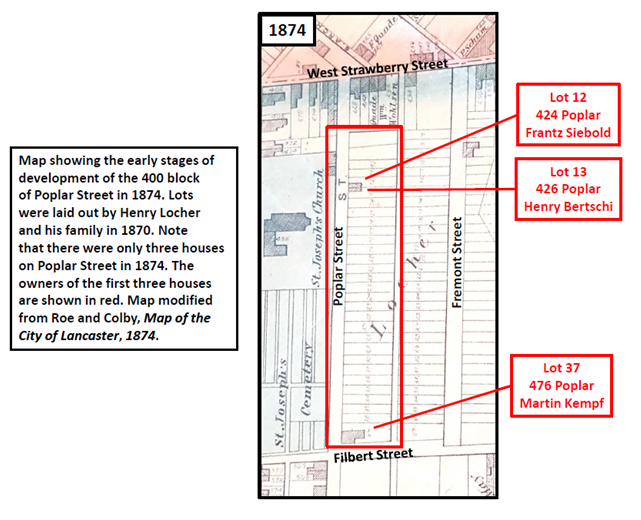

The first two houses to be built were completed by 1874 (see 1874 map). They were built by Frantz Siebold (lot 12) and Henry Bertschi (lot 13). Today those houses are 424 and 426 Poplar, across the street from the SoWe office in the rear of the St. Joseph Church annex. The third house built was that of Martin Kempf, who bought lots 36 and 37 for $475 about six months after the public sale. Kempf built a larger house on lot 37 on the corner of Poplar and Filbert, where he opened a beer saloon on the first floor. Kempf’s house and saloon is now 476 Poplar.

The purchase of lots from Locher’s heirs, and the building of houses on the lots, continued for another fifteen years. In 1880, eight years after the public sale, eight houses had been built (416-424, 476). Just six years later, in 1886, another twenty houses had been built (412-414, 426-430, 434-436, 442-448, 456-472). Finally, by 1888, sixteen years after the public sale, all thirty-one lots had been sold and all thirty-four houses had been built (see 1897 map). Every house was a 2-1/2-story brick Victorian house.

In a little more than fifteen years (1872-1888), the southeast side of the 400 block of Poplar Street had gone from boundary stakes in the ground to fully built out, testifying to the intense development of the Hill that was occurring at that time. Today, the same thirty-four houses that were built more than one hundred and thirty years ago are still present, making the 400 block of Poplar perhaps the only block on Cabbage Hill where all the original houses pre-date 1890 and are still in use.

Today’s residents of the 400 block of Poplar are living with a lot of history just waiting to be discovered. If you live in one of those houses, the history of your property dates back to the lots laid out by Henry C. Locher in 1870. That would be a good starting point from which to develop the rest of your house’s history to the present. If you are interested in researching your house’s history, you can contact me at SoWeCommunicate@sowelancaster.org, and I will try to point you in the right direction.