Jim Gerhart, November 2020

Cabbage Hill has been home to many successful businesses over the past 150 years, some of which have succeeded over several generations. Kunzler & Company, Inc. may be one of the first to come to mind. But not all successful Hill businesses lasted that long. One of the most successful businesses was the Helvetia Leather Company, which is largely forgotten today. However, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, working out of a large lot on Poplar Street, the company achieved nationwide recognition for its unique products, but it was in business for only about 30 years.

In the mid-1870s, Albert Wetter, a Swiss immigrant living on West Strawberry near South Water, began experimenting with a new way to make leather. By 1879, he had patented his new method, which used hot air instead of tannin to make leather from animal hides. Soon Wetter’s new method attracted several investors and together they started to manufacture “Helvetia leather”, a tough but pliable leather that was well suited to manufacturing applications. (Helvetia was the Roman name for Switzerland, Albert Wetter’s native country.)

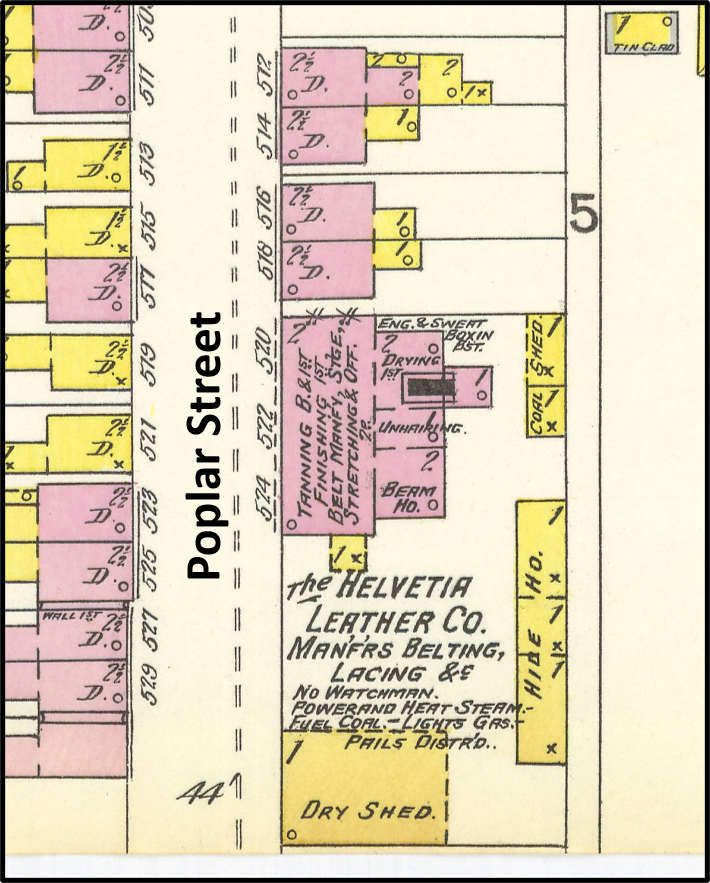

The new venture, known by the names of its largest investors, Potts, Locher, & Dickey, needed a place to conduct its business. In 1879, Wetter purchased a large lot on the southeast side of the 500 block of Poplar, where the houses at 520-538 are located today. The lot extended 202 feet along Poplar, and 87 feet to an alley that is now South Arch. Later, the company would purchase another lot adjacent to the first, this one fronting on Fremont 100 feet and extending 85 feet to the same alley from the opposite direction.

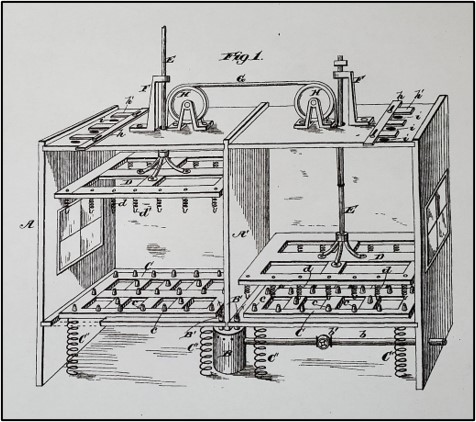

Wetter and his partners built a large two-story brick factory and associated frame and brick buildings in which they started producing leather using Wetter’s new method. The factory was powered by a steam engine using coal as its fuel source. Wetter purchased the house next door at 518 Poplar in 1880 and he, his wife Lizzie, and their son Robert moved in beside the factory. In 1882, Wetter enlisted the noted Lancaster inventor, Anthony Iske, to design machinery that would make the hot-air method of producing leather more efficient, and together they patented that machinery. The company began to make a name for itself in the heavy-duty leather field.

Ever since its founding in 1729, Lancaster had always had numerous tanneries. Tanning leather was a difficult and messy process. Fresh animal hides had to be purchased from butcher shops and farms, and they had to be cleaned, de-haired, cured, and dried for several weeks before they were ready to be tanned. Tanning usually was accomplished through the use of tannin, which was obtained from tree bark through a time-consuming process, but with Wetter’s new hot-air method, that part of the process could be avoided.

Even so, the tanning that took place on Poplar must have been a dirty, noisy, smelly activity, becoming especially bothersome as that block of Poplar was built out with houses in the 1880s. Also, tanning no doubt resulted in some nasty waste products that were drained off downhill into the small stream that ran where New Dorwart is located today. Following the burial of that small stream in a sewer under New Dorwart by the late 1890s, the company built their own sewer to connect to the one under New Dorwart, and discharged their waste that way.

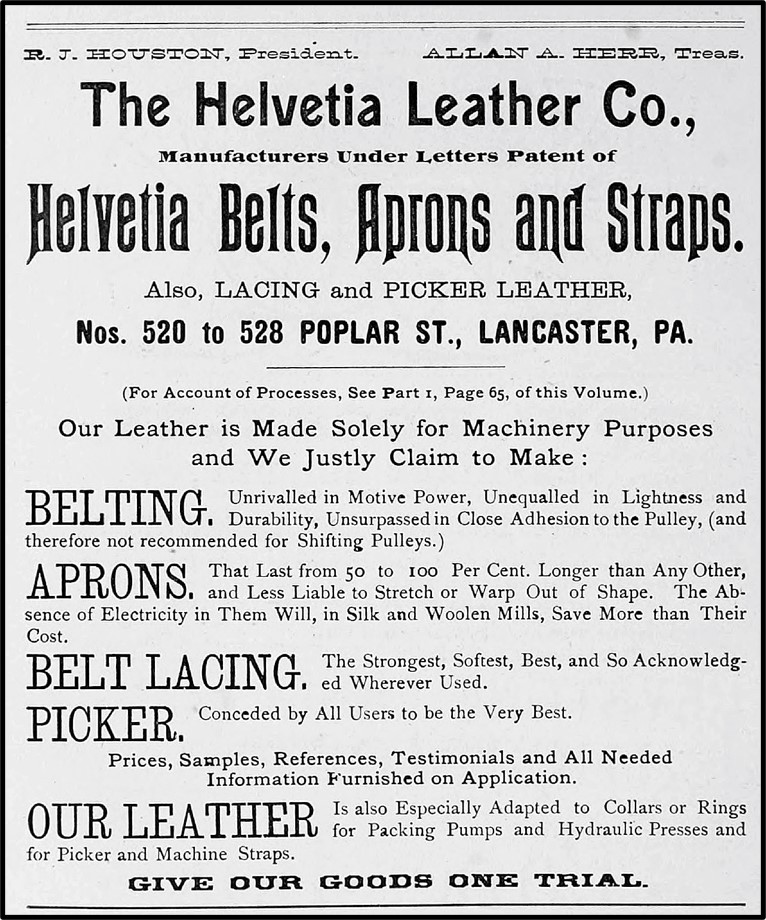

Unfortunately, due mostly to bad management, the first incarnation of Wetter’s business failed after a few years. Wetter and his partners were forced to sell the Potts, Locher, & Dickey business in 1882. The business was bought by a different group of investors headed by John Holman and Philip Snyder. After a few years of gradual success under its new management team, the business went public on September 7, 1886, sold shares, and became a corporation called the Helvetia Leather Company. (Wetter was not part of the newly incorporated business; in fact, he seems to have left Lancaster.) The growing company, chartered for the purpose of “tanning and manufacturing leather by patented or other process”, soon became famous for its leather, which was ideal for belts in machinery, laces for boots and shoes, industrial aprons, and similar uses.

The nationwide recognition of the company was mainly due to its belt leather, that is, belts used to run heavy-duty machinery in sawmills, cotton mills, silk mills, printing plants, iron forges, railroad shops, and similar factories. Helvetia leather was made only from the high-quality centers of the animal hides, with the edges being cut off and sold to other manufacturers of different leather products. The company’s leather belts were said to be strong yet pliable, no matter their thickness, and they could run machinery with less tension required than with other types of leather belts. The company’s belts performed equally well in cold and hot temperatures, and did not slip as much as others.

The Helvetia Leather Company made heavy-duty leather belts for factories as far west as South Dakota, as far south as the Carolinas, and as far north as Massachusetts. Companies such as the Lehigh Valley Railroad Company, the Nonotuck Silk Mills, the Lancaster New Era, and the Clark Mile End Spool Cotton Company installed belts made by the Helvetia Leather Company. In fact, the Clark Mile End Spool Cotton Company in Massachusetts used nearly two miles of Helvetia belting in its factory, with one single belt being more than 2,100 feet long, a record for the time.

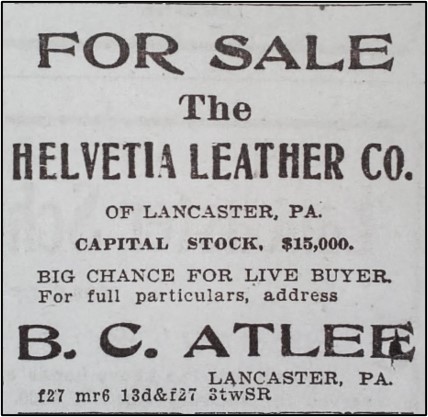

Throughout the 1880s and the 1890s, the Helvetia Leather Company on Poplar flourished under the leadership of John Holman and Philip Snyder, as well as several other prominent Lancaster businessmen. Robert Houston was President for most of those years, and local businessmen Allan Herr, Abraham Rohrer, Charles Landis, Elmer Steigerwalt, and Benjamin Atlee played important roles in officer positions. Gustavus Groezinger, owner of Groezinger’s Tannery at the foot of West Strawberry, also was an investor and officer. For many years, John Zercher was the factory superintendent, until he died suddenly at his desk one morning in 1906.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, Helvetia Leather Company had trouble paying its shareholders their annual dividends because of high prices for raw materials. By the end of the decade, the company struggled to meet expenses, no doubt partly because of the rising popularity of rubber belting. As a result, the company was put up for public sale in 1909, but the reserve amount was not met. It was finally sold in 1910 to Henry Schneider, and its buildings were almost immediately razed to make room for new houses. Within two years, eight two-story brick houses had been built at 520-534 Poplar.

Two small, unusual houses at 536-538 Poplar are all that remain of the Helvetia Leather Company’s complex of buildings; these two houses used to mark the southwestern extent of the tannery property. Looking at the row of eight tidy houses just uphill from 536-538 now, it is difficult to imagine that, in their place, a large, busy, noisy tannery once produced machinery belts and other products that helped run factories all around the country. Today, the Helvetia Leather Company is just another ghost of Cabbage Hill past.