Jim Gerhart, October 2020

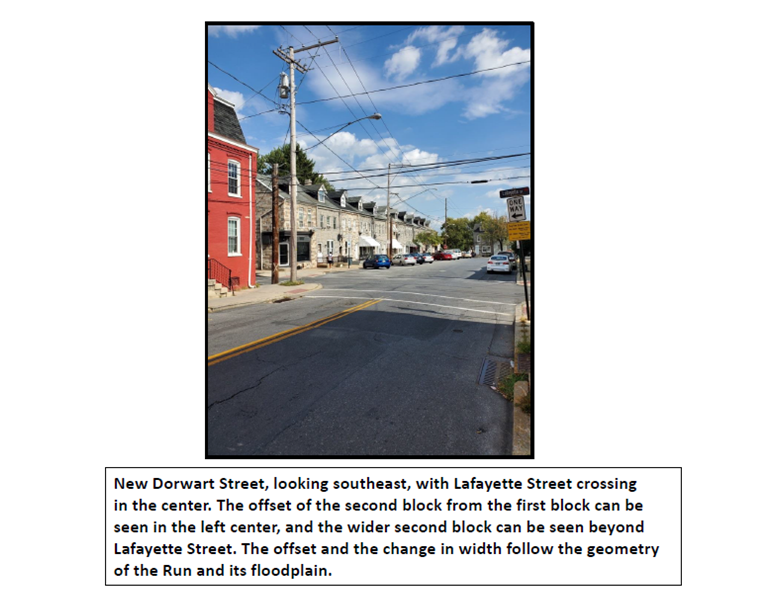

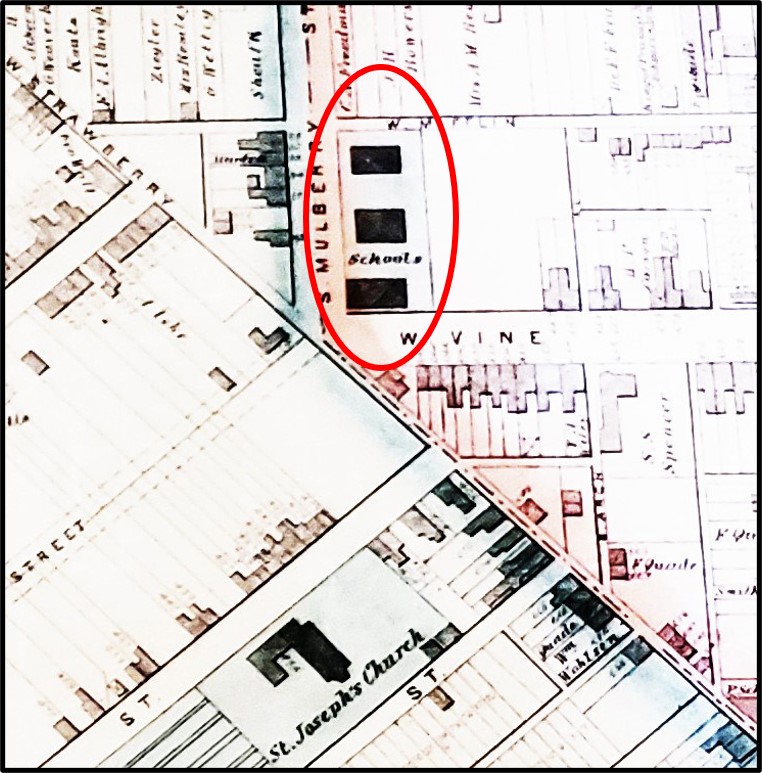

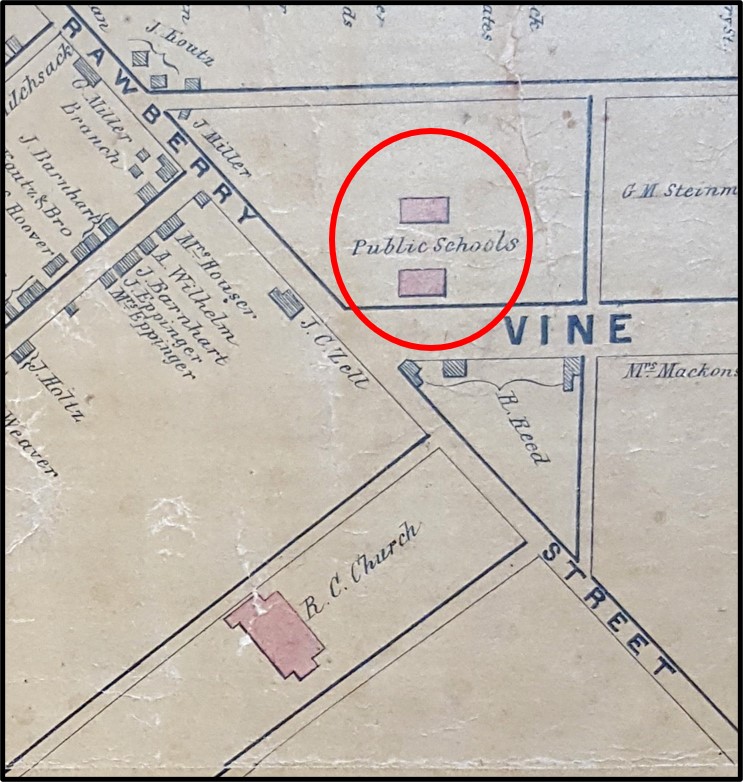

The five-point intersection of West Strawberry, South Mulberry, and West Vine Streets, which is the gateway to Cabbage Hill from downtown Lancaster, has witnessed a lot of history. On the northeast corner of the intersection, bounded by South Mulberry and West Vine, a large school building now stands on a lot where 170 years ago some of the very first schools of Lancaster’s public-education system once stood. Let’s peel back the layers of school history at this site, starting with the first layer (today) and working back to 1850, with the emphasis on the fourth (earliest) layer, about which less is commonly known.

Layer 1, 1992-2020–The first and most recent layer of school history at this intersection covers 1992 to the present. Housed in the large Victorian-era brick building on the northeast corner of the intersection is the Intensive Day Treatment Program run by Catholic Charities of the Harrisburg Diocese. The program offers a five-day-a-week program of counseling, therapy, and life-skill education for at-risk Lancaster County children between the ages of nine and fifteen.

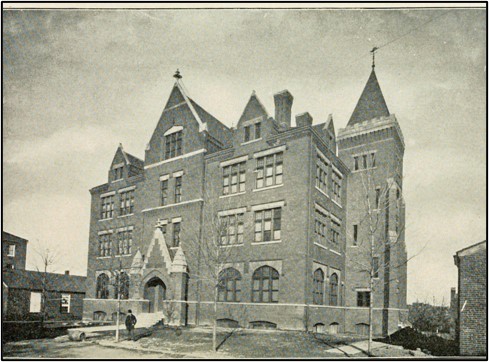

The Victorian-era school building on the northeast corner of South Mulberry and West Vine. Photo taken in 2020.

Layer 2, 1939-1992–The second layer of school history, just beneath today’s surface layer, covers 1939 to 1992. Many long-time residents of Cabbage Hill will remember this layer, when the current large brick building was the home of St. Joseph Catholic School. The Harrisburg Diocese bought the building on behalf of St. Joseph Catholic Church on July 10, 1939, and established a parochial school for the education of Catholic children on the Hill. The diocese purchased the building from the Lancaster City School District for $22,500 and renovated it to meet St. Joseph Church’s needs. The purchase was made to ease the crowding of the school located next to St. Joseph Church a block away. Many Cabbage Hill children received their primary-school education at St. Joseph School.

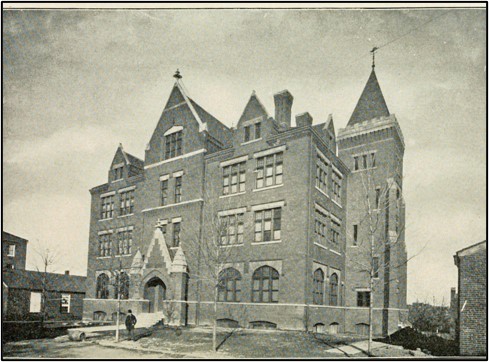

Layer 3, 1892-1939–Peeling back the second layer of school history, we expose the older third layer, which covers 1892 to 1939. No doubt there are a few old-timers who remember at least the later years of this layer, which begins with the completion of the current large brick school by the School District of Lancaster in 1892, and ends when the building was sold to the Harrisburg Diocese in 1939. The building currently at the site, then known as the South Mulberry Street School, was part of the City of Lancaster’s public-school system for nearly fifty years, and served as both a primary and secondary school. It was built to accommodate the growing numbers of students that resulted from increased immigration to the Cabbage Hill area in the late nineteenth century.

The architect who designed the South Mulberry Street School (1892) was James H. Warner, who also designed several other prominent buildings in Lancaster at about the same time, including Central Market (1889) and Christ Lutheran Church (1892). It is not surprising that the exterior of the South Mulberry Street School bears a strong resemblance to the exteriors of these other two buildings, in that all three are built in similar Victorian style with red brick highlighted by decorative brownstone accents.

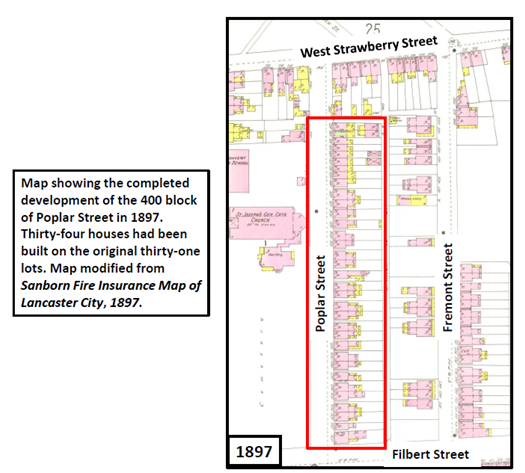

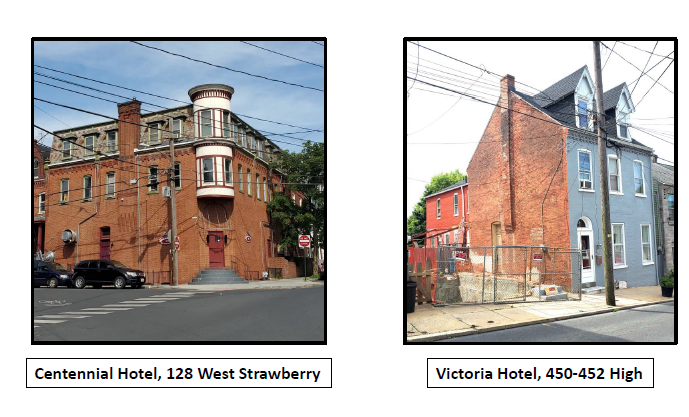

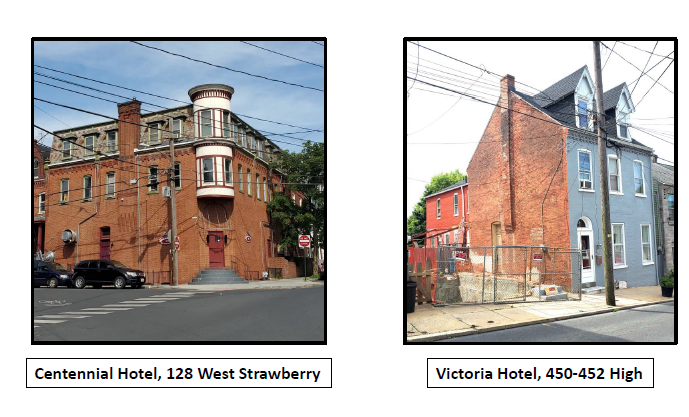

Also built about the same time and in similar style was the three-story Victorian-era brick building on the corner across West Strawberry that until recently housed the Strawberry Hill Restaurant, and was originally the Centennial Hotel. In addition, the grouping of three three-story brick houses diagonally across the intersection, and directly facing the intersection on the south corner, was built in the 1890s. The late Victorian makeover of the intersection was complete by the late 1890s.

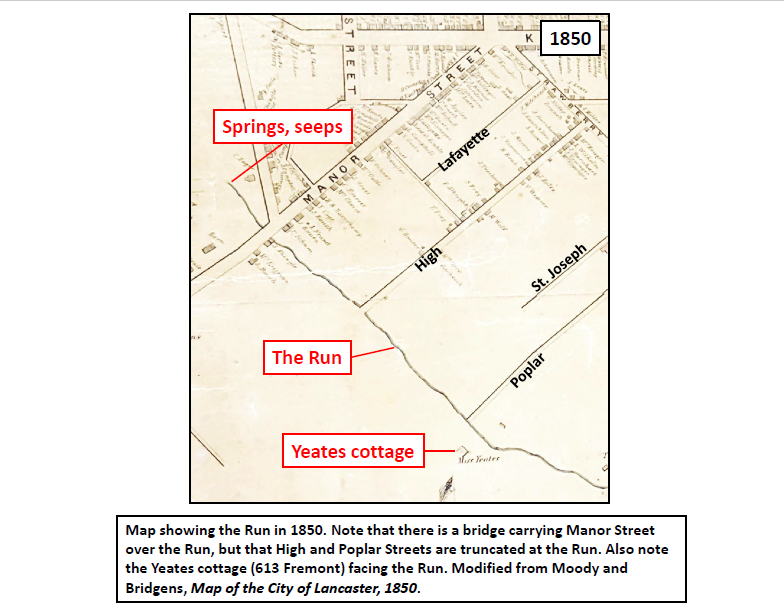

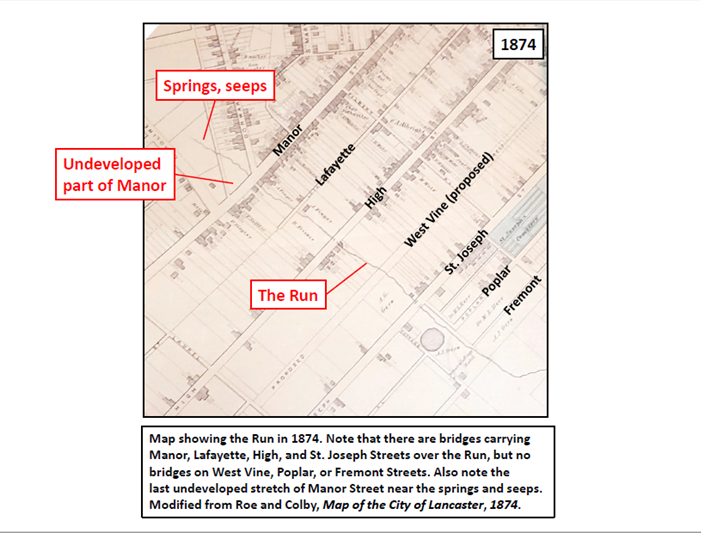

Layer 4, 1850-1892–Finally, way down in the layers of school history at this site is the fourth and earliest layer. It begins in 1850 and ends in 1892, when the large school building now on the site was completed. To clear the ground for the large current building, the School District of Lancaster razed two older school buildings built in 1850 and a third school building built in the late 1860s. All three of the earlier buildings were one-story brick buildings, with the third building being slightly larger than the first two.

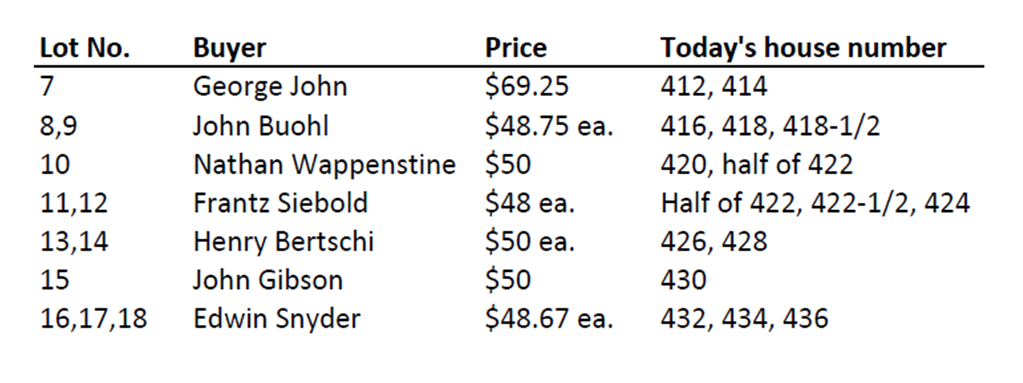

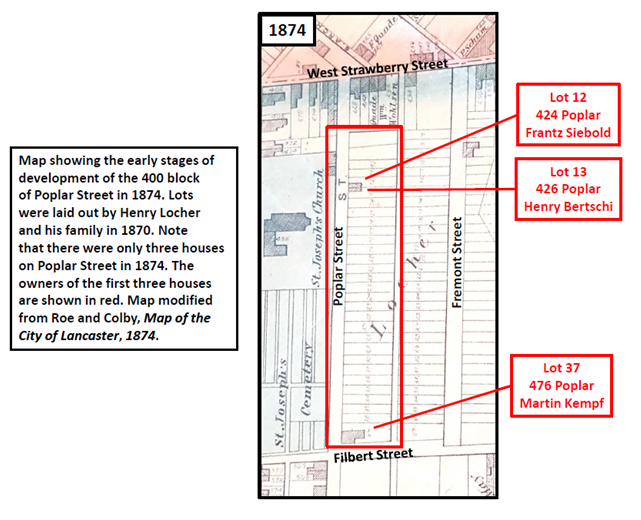

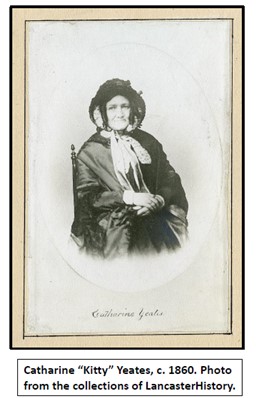

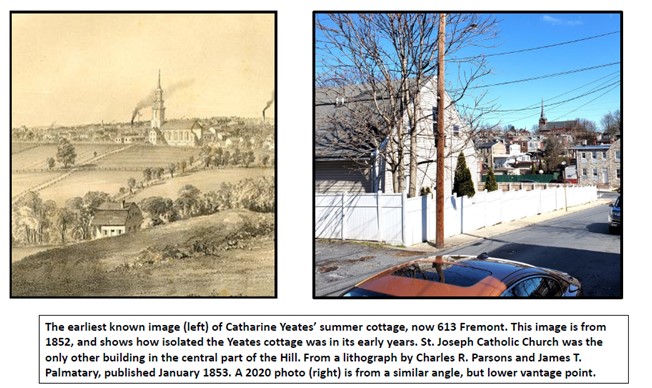

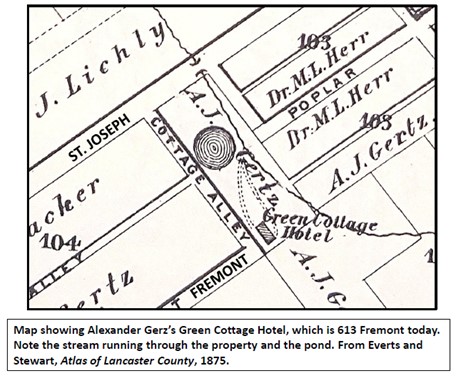

The first two of these early school buildings were among the very first public-school buildings built in Lancaster following the implementation of the city’s common (public) school system in the early 1840s. The first two buildings—essentially double one-story brick houses—were built in 1850. They were built on Hamilton lot 386, one of the original building lots laid out by James Hamilton in 1730. Lot 386 had been purchased by the Board of Directors of the Common Schools from Margaret and Catharine Yeates, daughters of Judge Jasper Yeates, on June 26, 1849, for $300. The lot was 64 feet on West Vine, extending 242 feet to Mifflin.

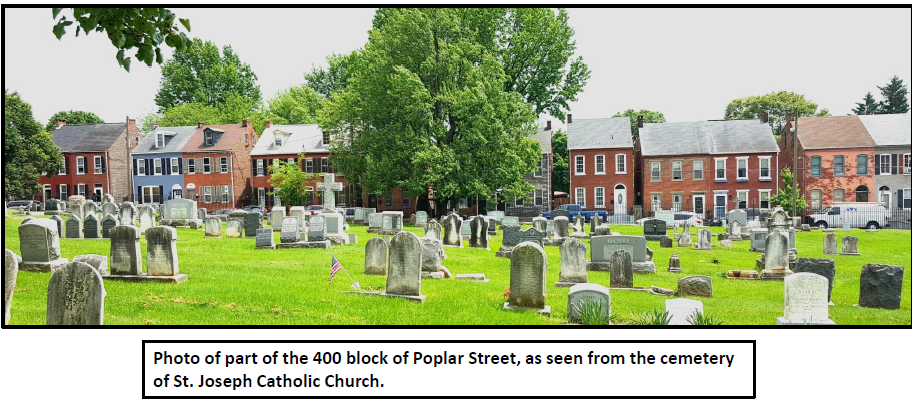

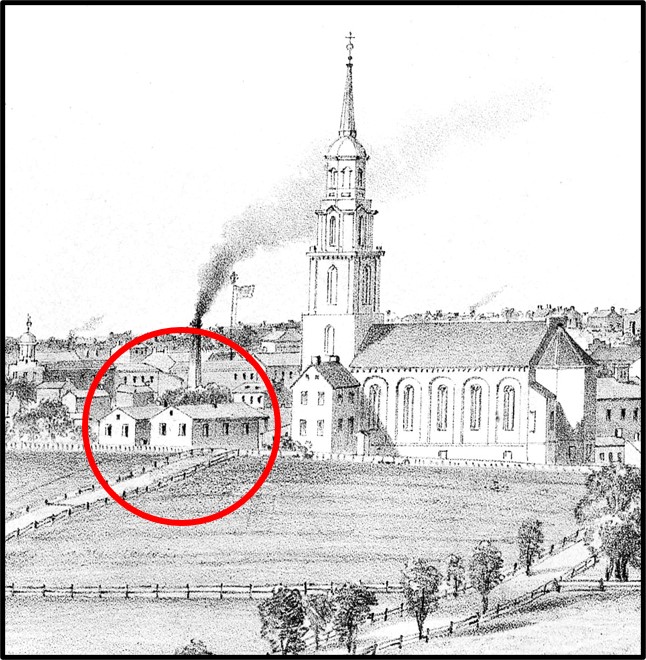

At the time the Board of Directors purchased lot 386 and built the first two school houses, South Mulberry did not yet exist; Mulberry’s southern extent ended at West Orange. As a result, the two school houses were referred to as the West Vine Street School until Mulberry was extended in the mid-1850s. Also, when the school houses were first built, West Vine did not exist south of West Strawberry. Therefore, today’s distinctive five-point intersection was only a three-point T-intersection with the north part of West Vine truncating at West Strawberry, which was still a narrow dirt lane. In addition, in 1850, the foundation of the first St. Joseph Catholic Church was just being dug, and today’s Christ Lutheran Church was still several decades in the future.

Lot 386 was near the top of Dinah’s Hill and it looked out on downtown Lancaster to the north and was bounded on the south, in 1850, by pasture land of the still undeveloped central part of Cabbage Hill. Across West Strawberry to the south was Christopher Zell’s one-story frame blacksmith shop that would soon be enlarged into the Centennial Hotel and Saloon. There were only a few other buildings within a block of the two school houses, including the small log cabin across West Vine where 113-year-old ex-slave and fortune-teller Dinah McIntire had lived several decades before, giving her name to the hill on which lot 386 was located.

When the first two small school buildings opened in 1850, they served both primary- and secondary-age children, mostly of German heritage. It didn’t take long for the two school buildings to become crowded as Cabbage Hill began to grow. Anticipating and reacting to that growth, the Lancaster School District acquired two more pieces of land adjacent to lot 386—a 16-foot strip of land between lot 386 and the recently extended South Mulberry to the west in 1860, and a 24-foot strip of land on the east side of lot 386 in 1878. Both strips of land extended to Mifflin.

The third school building was added to the south of the first two in the late 1860s to serve as a primary school for both boys and girls. It was a little larger and sat a little closer to South Mulberry, taking advantage of the strip of land added in 1860. By the late 1880s, the three small school houses were again becoming crowded as well as outdated, prompting the School District to plan for their replacement by a larger, more modern building—the one that is on the site today.

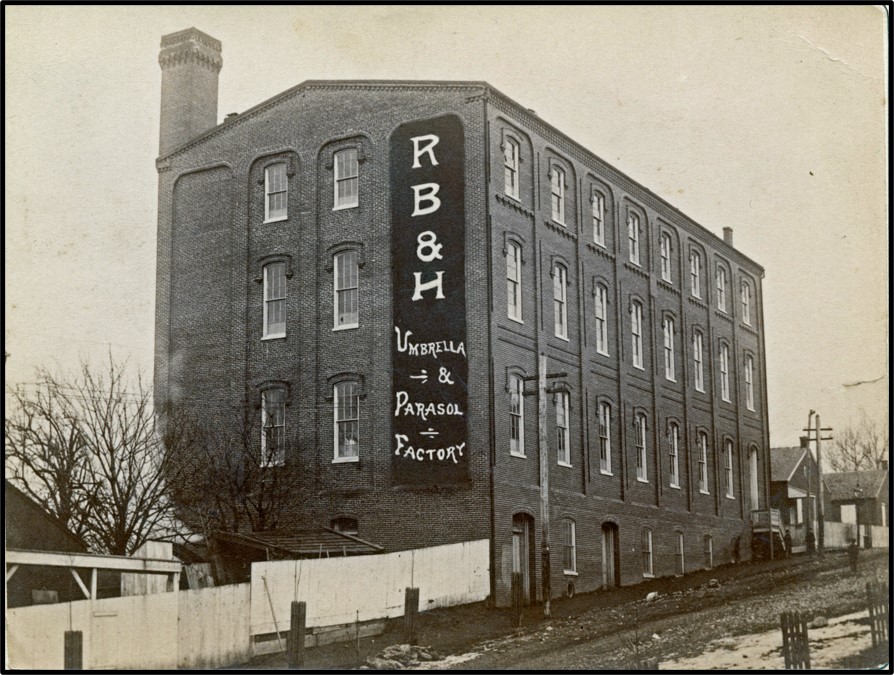

It would, of course, be historically interesting to have a photograph of the three early public-school buildings before they were torn down in the early 1890s, but it seems there are none devoted to just the three buildings themselves. However, partial images of the first school houses on the site were inadvertently captured in the corners of two other photographs before the early school houses were forever lost to history.

First, in the late 1880s, a few years before the current building was built, a photographer from the Fowler Gallery took a picture of the Rose Bros. & Hartman Parasol & Umbrella Factory in the first block of South Mulberry. This factory would soon be expanded down to West King and become the Follmer, Clogg & Company umbrella factory, and today the Umbrella Works Apartments. On the right edge of the photograph one can see the fronts of the first two small, one-story, brick school houses built in 1850.

Then, in 1892, when the current larger building had just been finished, a photograph was taken to commemorate its completion. On the left edge of the photograph can be seen the side of one of the first school houses built in 1850, and on the right can be seen the front edge of the third school house built in the late 1860s. It seems that only the middle school house had to be torn down to build the new larger school, and the other two were used for classes while the new larger school was being built. Then, when the new school opened, the remaining two old school houses were torn down.

One can learn a lot about the evolution of schools at this iconic five-point intersection just by using historical records and photographs to peel back the layers of history.