Jim Gerhart

August 1, 2019

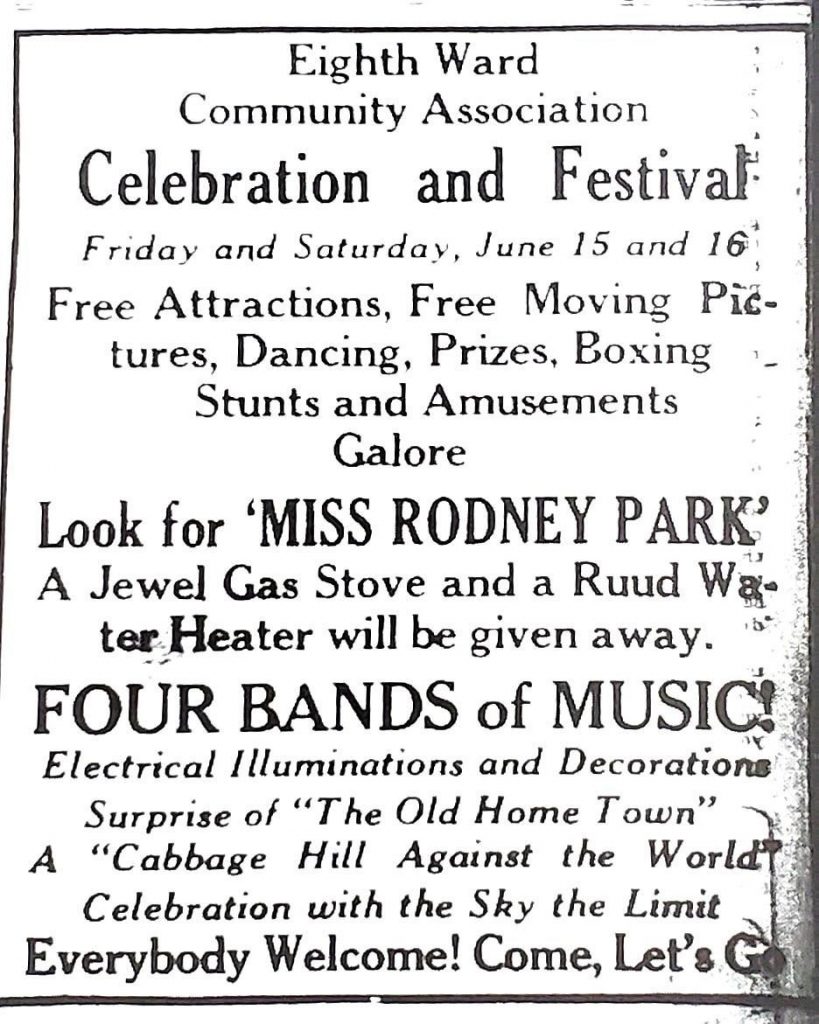

The greatest expression of civic pride ever to take place on Cabbage Hill in the Eighth Ward of Lancaster occurred on June 15-16, 1923. On the evenings of those two days, a huge festival drew close to 10,000 people to Manor Street to celebrate the long-awaited completion of the paving of the street. More than $6,000 (about $84,000 in today’s dollars) was raised to benefit Rodney Park, a new city park on a triangle of land between Third, Rodney, and Crystal Streets.

The surface of Manor Street had been in terrible condition for many years. Finally, in early August 1922, work crews began the process of excavating the street so it could be paved with concrete. The city’s contractor, Swanger-Fackler Construction Company of Lebanon, was responsible for the overall project and the paving of most of the street, and Conestoga Traction Company was responsible for moving the trolley tracks from the edge of the street to the middle, and paving the street around the trolley tracks. The work proceeded slowly, as the crews ran into several unexpected complications as they excavated 150 years’ worth of old street surfaces.

When cold weather set in during the late fall and concrete could no longer be poured, work was halted for the winter, leaving some sections of the street torn up and virtually impassable. Fortunately, by the first week of April in the spring of 1923, the weather was good enough for the crews to get back to work. Progress was steady throughout April and May, and by late May the residents of the Eighth Ward were hopeful that the work would finally be completed by mid-June.

The Eighth Ward Community Association met on May 25, May 31, and June 7 to develop plans for a festival to celebrate the opening of the newly paved Manor Street. The festival was scheduled for June 15-16, 1923, and the Association decided to dedicate the proceeds of the festival to outfitting Rodney Park—acquired by the city just two months earlier—with playground equipment and a surrounding sidewalk for roller-skating.

In late May, the Association canvassed door to door in the Eighth Ward to gauge the level of interest and ask for donations to support the festival. The canvassing generated much enthusiasm and many donations; in fact, the level of interest was so high that the Association decided to expand the scope of the event from just a Manor Street opening to “A Cabbage Hill Celebration and Festival”. One of the leaders of the Association said that “this is the first time in the history of the city that such a celebration has been held” and that “it is for all the people”.

To plan the festival, twenty-six committees were established, with each committee having a chairman and three to five other men as members. The women had their own committees, most of which corresponded in topic with the men’s committees, and the two sets of committees worked together to prepare for the festival. Committee chairs were selected for their expertise in the area of the committee’s topic. For example, Christ Kunzler of Kunzler’s Meat Market was the chair of the Hot Frankfurter committee, and Leo Houck of boxing fame was the chair of the Sports committee.

The committees included: Program, Publicity, Music, Decorations, Amusement, Sports, Dancing, Candy, Prizes, Hot Frankfurters, Soft Drinks, Popcorn, Flowers, Ice Cream, Fruit, Truck, Ice, Printing, Cigars, Equipment, Lumber/Chairs/Tables, Public safety, Tags, Cakes, Novelties, and Fancy Work. Probably to many people’s chagrin, there was no Beer committee—at least not officially—because the 18th Amendment (Prohibition) had gone into effect a few years earlier.

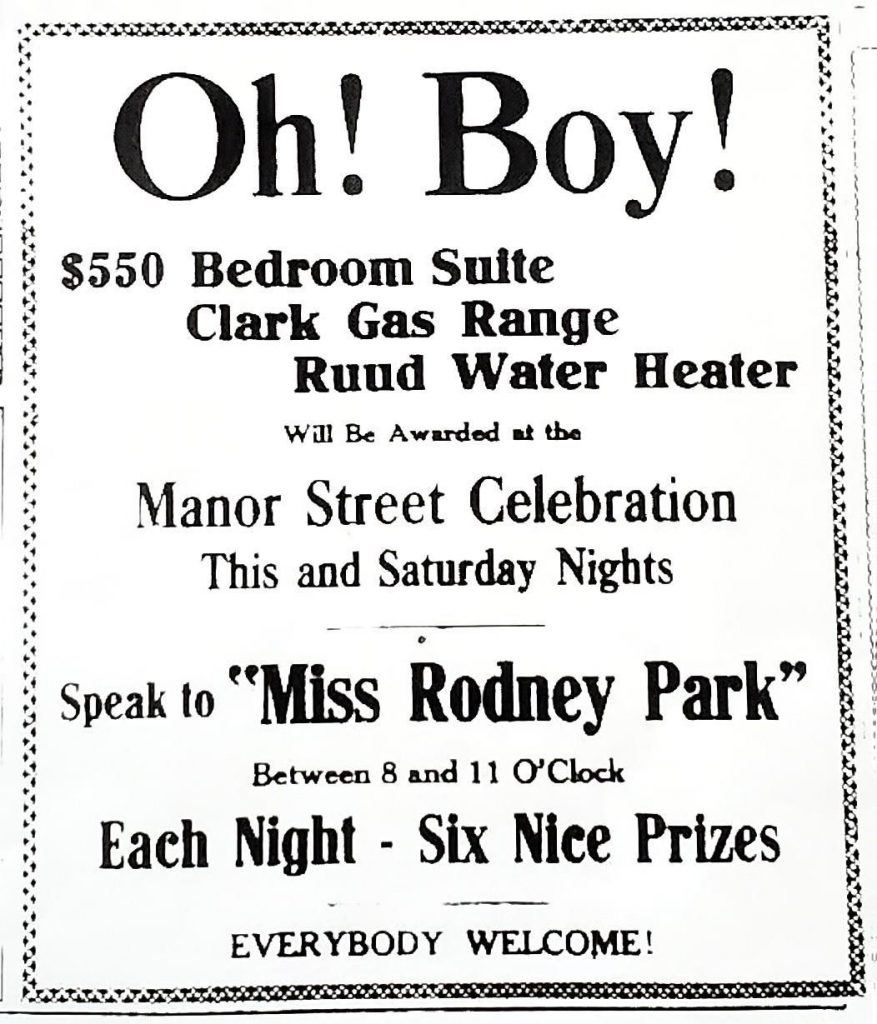

In the days leading up to the festival, several items were donated to be used as prizes. Congressman William Griest donated a new Ruud water heater that was put on display in the window of Louis Fellman’s hardware store (568 Manor Street) to help ratchet up interest. The Conestoga Traction Company donated a new Clark Jewel gas range, which was also displayed at Fellman’s store. The Friends of the Eighth Ward Community Association donated a $550 mahogany bedroom suite that was displayed at Hoffmeier’s furniture store on East King Street near the square.

Cash donations also were made. Christ Kunzler took up a collection of $87 at an Elks Club dinner held the week before the festival, and he also paid for the first hour of music by a band at the festival. Hamilton Watch Factory and Armstrong Linoleum Company each gave $50, as did the Fraim-Slaymaker Lock Company. The Select Council also presented a cash donation. In addition, the Intelligencer Journal and the Examiner-New Era newspapers would supply Rodney Park with a drinking fountain and a flagpole.

To the relief of all the committees, the paving of Manor Street was completed on time, and by the afternoon of Friday, June 15, the final preparations for the festival were underway. Two large banners were strung across the street at the ends of Manor Street—one at the crest of the hill near West King Street and one near South West End Avenue. American flags and bunting were displayed along the street and on many of the houses (Flag Day was the previous day), and colored electric lights were strung along and across Manor Street from West King Street to Fairview Avenue. Dozens of booths that had been built by the residents and decorated with flowers lined the street on both sides.

It was partly cloudy and about 80 degrees when the festival kicked off at 6:30 p.m. Friday evening. At that time, the leaders of the Eighth Ward Community Association, the American Legion Band, and some 500 school children of the Eighth Ward departed in a parade from the intersection of Manor and Dorwart Streets. They marched to City Hall, where they met Mayor Frank Musser and other city officials and escorted them back in the parade to the intersection of Manor and West King Streets, where a fence barrier had been erected across Manor Street.

At the barrier, the mayor was presented with a new axe, and with one stroke he broke through the ceremonial barrier, officially opening the newly paved street. Immediately after the barrier was broken, a chorus of children sang a welcoming song, and a switch was flipped, lighting all the colored electric lights along the street. The Star Spangled Banner was played, followed by a short speech by the mayor. At the end of the ceremony, the whole group of officials, school children, and the American Legion Band paraded the length of Manor Street to great cheering. The festival was officially underway.

For the festival, Manor Street was divided into three segments, each with a distinct focus—dancing, boxing, and amusements. Four bands, including the American Legion Band, the Iroquois Band, and the City Band, participated over the two nights, and each one was stationed at a different segment. The segments were linked together by the strings of colored lights that extended along the entire stretch of the street, and by 33 booths that lined the streets between the segments, offering the Eighth Ward’s best food, drinks, clothing, novelties, and hand-made items for sale.

The block of Manor Street between Laurel Street and Fairview Avenue was set aside for street dancing, with the music supplied by the American Legion Band. Rousing Roaring Twenties music was no doubt on the program, and the young people of the Eighth Ward danced until the festival closed each night. At one point during the dancing, the lights briefly went out, and the newspaper slyly reported that this unexpected feature was much appreciated by the young revelers.

The intersection of Manor and Dorwart Streets was designated for exhibition boxing matches, and a ring was set up in the street. Each night, there were five, three-round exhibition matches arranged by Leo Houck, the Eighth Ward’s own boxing hero. One match was for the championship of the Fraim-Slaymaker Lock Company (Young Biddy vs. Willie Bloom) and another was for the 125-pound title of Manor Street (Battling Fuzzy vs. Kid Carney). The final, much anticipated match was Leo Houck, who had fought many of the world’s best boxers in the previous two decades, facing off against his long-time sparring partner, Jule Ritchie. Unfortunately, Ritchie was late and the feature bout had to be replaced with a quickly arranged one between two different boxers.

The intersection of Manor and Third Streets was set up for amusements. Eddie Fisher, a well-known local clown, was in charge of the program at this location. Each night, the YMCA provided a gymnastics and stunts exhibition, and Fisher and a troupe of clowns performed. A little farther down the hill, the Strand Theater in the 600 block of Manor Street provided a free showing of a silent movie, and Brinkman’s Metropolitan Four sang a selection of songs. On Saturday night the Strand hosted a public wedding of a couple from Columbia, officiated by a pastor from Marietta.

An unusual feature of the festival that must have served as a good ice breaker was the Miss Rodney Park contest. Each evening, in three different hour-long time slots, a secretly selected young woman was designated as Miss Rodney Park for that hour. She went out among the crowd incognito and the first person who approached her with “You are Miss Rodney Park”, would be the prize winner for that hour. No doubt many young women were approached by many young men, but Miss Rodney Park was only correctly identified three times.

By the time midnight rolled around on Saturday night and the festival was over, it was clear to everyone that it had been a much bigger success than anyone had imagined. The crowds had been huge (almost 10,000 over two nights), the booths were almost completely sold out of their merchandise, and every featured event on the program had been a big hit. Over the next couple of days, as cleanup took place, the Eighth Ward Community Association counted up the proceeds and decided on the distribution of prizes, which were then awarded on Tuesday night, June 19, at Fellman’s hardware store. The amount of money raised exceeded $6,000, and on the night of June 20, again at Fellman’s store, the Community Association met with the City Parks Committee to discuss how to best use the money for Rodney Park.

The Eighth Ward had done itself proud. For two nights, the residents had channeled their abundant civic pride into accomplishing the largest festival ever seen on Cabbage Hill. The people of other parts of Lancaster who had joined in the festivities left with “a lot of respect for the manner in which the Eighth Ward does things”, as one of the newspaper articles put it. It was hoped that the paving of the street and the successful festival might end the long held opinion that Cabbage Hill was not treated like a fully accepted part of the city. In fact, one of the newspaper articles stated that the reconstruction of the street was “the first thing worth while the Hill has ever gotten from a city administration”. At least for two nights, on June 15-16, 1923, Cabbage Hill had finally gotten its due.

The City of Lancaster and SoWe are committed to promoting the same kind of neighborhood pride that made the 1923 celebration such a success. The city has installed pedestrian-style streetlights along Manor Street and part of West King Street, and has started the process of planting trees along the street as well. And SoWe, with its many partners, is working on numerous initiatives to build neighborhood pride, including a cost-sharing program to improve building façades on Manor Street, especially those that once had storefronts. It is hoped that all these efforts will help rekindle some of the proud neighborhood spirit of the past.